HEMOTHORAX

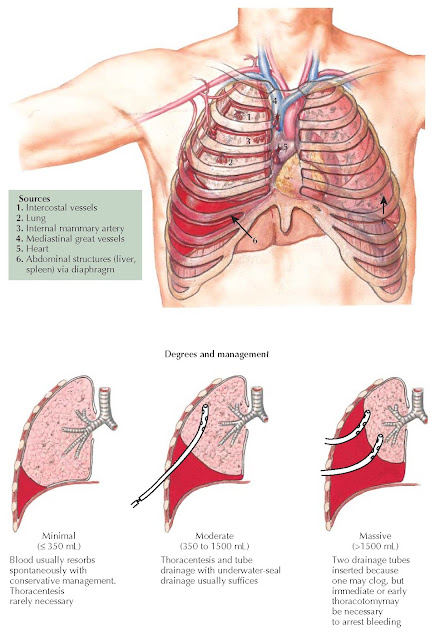

Hemothorax is bleeding into the pleural cavity; the source of bleeding can be from a variety of structures in the thorax or from the abdomen through a diaphragmatic injury. The most common cause of hemothorax after blunt trauma is the chest wall with disrupted parietal pleural allowing blood loss from torn intercostal vessels to enter the pleural cavity; after penetrating injuries, it is usually from the lung parenchyma. Persistent bleeding into the thorax suggests a systemic source, usually an intercostal or internal mammary artery, but occasionally a named thoracic vein (e.g., azygos, subclavian, or pulmonary) will produce ongoing blood loss. Typically, a hemothorax from a ruptured thoracic aorta, pulmonary artery, or heart is extensive at the time of emergency department arrival. Of note, occasionally, the source of major persistent bleeding in the thorax originates from the liver or spleen via an associated diaphragmatic injury.

The diagnosis of hemothorax is usually established by

chest radiography or with the presumptive placement of a chest tube in a

patient arriving in hemorrhagic shock. Hemothorax is recognized more frequently

with computed tomography (CT) scanning because small collections are seen that

are not apparent on chest radiography. Management is dictated by the size of

the hemothorax and physiologic condition of the patient. In general,

hemothoraxes can be considered minimal if they are smaller than 350 mL,

moderate at 350 to 1500 mL, and massive above 1500 mL. Minimal hemothoraxes are

usually first identified by CT scanning and can be treated expectantly. Moderate

hemothoraxes warrant tube thoracostomy because this evacuates the blood

completely; reexpands the lung, which tamponades chest wall bleeding; and

permits monitoring of continued blood loss. A chest tube placed for moderate

bleeding should be relatively large (e.g., 28 Fr in women and 32 Fr in men).

|

| Plate 4-139 |

The tube should be placed after ample chest wall

preparation and generous local anesthesia. An incision should be made in the

midclavicular line at a relatively superior location on the chest wall (i.e.,

the fifth intercostal space) to avoid injury to the liver or spleen caused by a

high-lying diaphragm. A gloved finger should be inserted into the pleural space

to ensure proper positioning, and the tube should be directed into the lung

apex with a blunt clamp. After it is in position, 20 cm H2O is applied to the

chest tube to evacuate the pleural cavity quickly. Finally, the tube should be

sutured securely to the chest wall to avoid dislodgement during patient

transport. Follow-up radiography is essential to ensure good tube placement and

complete removal of the hemothorax. The initial management of a massive

hemothorax is similar except that a large chest tube (i.e., 36 Fr) should be

used. If the follow-up chest radiograph does not show complete blood

evacuation, a second large-bore tube

should be inserted.

The decision for emergent thoracotomy is largely

determined by the patient’s response to tube thoracostomy in conjunction with

evidence of ongoing bleeding. In general, an initial return of more than 1500

mL or the failure to eliminate a hemothorax with two chest tubes, referred to

as a coked hemothorax, warrants exigent thoracotomy. There is also

general agreement that chest tube output greater than 250 mL/h for 3 successful

hours requires thoracic exploration, although video-assisted thoracoscopy (VATS) may be reasonable

in hemodynamically stable patients. Alternatively, angioembolization may be

appropriate if the suspected source of persistent bleeding is an intercostal

artery. If a patient fails to resorb a moderate hemothorax after 72 hours or if

there is a delayed hemothorax refractory to tube thoracostomy, VATS is a very

effective maneuver for definitive removal of the retained hemothorax.