FIBROCYSTIC CHANGE

III— CYSTIC

CHANGE

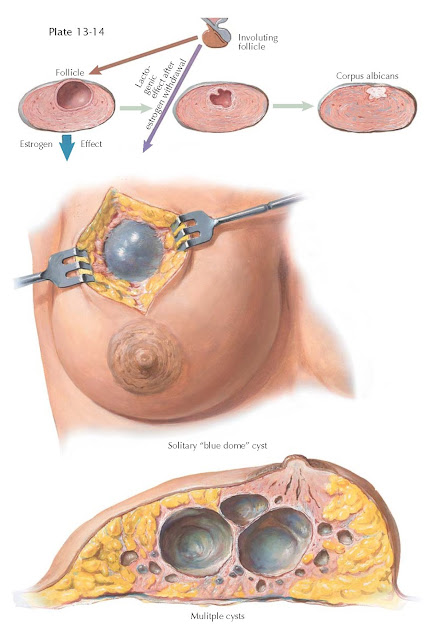

Cystic breast masses are frequently encountered in the clinical care of women. Sorting out those that represent a threat from those that may be followed conservatively is the challenge posed by the presence of cysts in the breasts. Some authors estimate that cysts form in the breasts of roughly 50% of women during their reproductive years. Roughly one in four women seek medical attention for some form of breast problem; often this takes the form of a palpable mass. The most common cause of a palpable breast cyst is fibrocystic change (found in 60% to 75% of all women). Dilation of ducts and complications of breastfeeding (galactoceles, abscess) may also cause cysts.

The pathogenesis is not clear for

the most common types of cyst formation. Cyclic changes in hormones induce

stromal and epithelial changes that may lead to fibrosis and cyst formation.

Cysts may be single or be found in clusters, with some up to 4 cm in diameter.

Small cysts have a firm character and are filled with clear fluid, giving the cyst

a bluish cast. Larger cysts may have a brown color resulting from hemorrhage

into the cyst. Inspissated secretions or milk may form a cystic dilation of

ducts (galactocele, ductal ectasia) that may be palpable as a cystic mass.

Variable degrees of fibrosis and inflammation may be seen in the surrounding

stroma. (Leakage of cyst fluid into the surrounding tissue induces an

inflammatory response that may alter physical findings and imitate cancer.) The

microscopic findings associated with breast cysts depend on the pathophysiologic

changes involved.

In fibrocystic change, the cyst makes

its appearance abruptly in a previously normal breast in which the parenchyma

has been largely replaced by fat and is accompanied by a sticking or stinging

sensation. A serous discharge from the nipple occurs in about 6% of the

patients. On palpation a tense, movable, rounded mass is felt fluctuating

between the fingertips of the right and left hands if the two hands alternately

compress the mass. On transillumination, both the breasts and the tumor

transmit the light readily. The cyst

usually occupies a region midway between the nipple and the periphery of the

breast.

On gross examination (when the cyst

is exposed at operation), it has a characteristic blue dome that bulges into

the subcutaneous fat. This cyst has a thin, fibrous wall, which may have an

epithelial lining of duct cells resembling sweat gland epithelium. On opening

the cyst, a smoky or cloudy straw-colored fluid is evacuated. Microscopically,

the cyst wall is embedded in dense, fibrous mammary stroma. The gland is poor in

acinar tissue.

The diagnosis and management of

cystic masses in the breast are based on history, physical examination, and

aspiration, with the occasional adjunctive use of mammography and

ultrasonography. (Ultrasonography is useful in differentiating solid and cystic

breast masses, but it has limited spatial

resolution and cannot be used to differentiate benign and malignant tissues.)

Needle aspiration with a 22- to 25-gauge needle may be both diagnostic and

therapeutic. If the cyst disappears completely and does not reform by a 1-month

follow-up examination, no further therapy is required. Fluid aspirated from

patients with fibrocystic changes is customarily straw colored. Fluid that is

dark brown or green occurs in cysts that have been present for a long time but is also innocuous. Bloody fluid requires

further evaluation. Cytologic evaluation of the fluid obtained is of little

value because of unacceptably high falsepositive and false-negative results.

After aspiration of a cyst, the patient should be rechecked in 2 to 4 weeks.

Lack of complete resolution at the time of aspiration, recurrence of the cyst, or

the presence of a palpable mass should prompt additional evaluation, such as

fine-needle aspiration (FNA) or open biopsy.