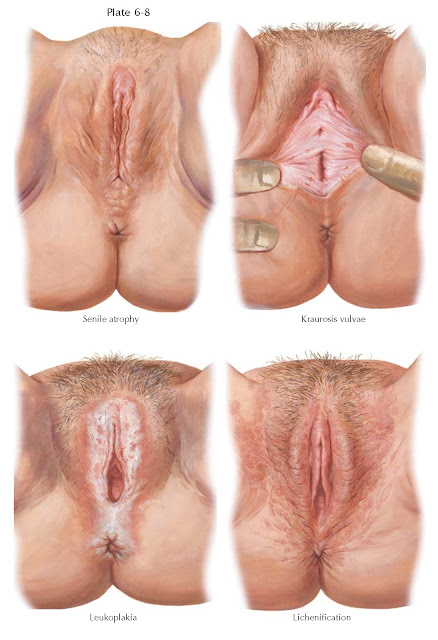

ATROPHIC CONDITIONS

Senile atrophy may follow natural or surgical menopause, or loss of ovarian function by chemotherapy (alkylating agents) or x-ray therapy. It is the result of the loss of estrogen stimulation to the genital tract. The skin changes are variable in degree and slowly progressive. With the loss of subcutaneous fat beneath the mons veneris and labia majora, the vulva assumes an increasingly shrunken appearance. The pubic hair becomes thin, sparse, and brittle. The labia minora, clitoris, and prepuce are reduced in size. The skin becomes thin, inelastic, shiny, and occasionally depigmented. Microscopically, the stratified squamous epithelium is reduced in thickness and there is a loss of elastic fibers. The underlying connective tissue shows evidence of decreased vascularity and increased fibrosis.

In the past, the terms kraurosis vulvae and leukoplakia were

applied to these atrophic changes. The term leukoplakia was applied when

there was primarily an inflammatory process; kraurosis vulvae was essentially an

extreme degree of atrophy. These terms have been discarded in part because

abnormal lesions of the vulva require biopsy to establish a correct diagnosis

and to rule out the possibility of an occult malignancy (present in 4% to 6% of

cases of lichen sclerosis).

Atrophic vulvitis (the former kraurosis vulvae) is a progressive

sclerosing atrophy of marked degree, resulting in stenosis of the vaginal

opening and effacement of the labia minora and clitoris. Dyspareunia is a

common complaint because of dryness and the shrink age of the vaginal introitus and canal. The vulvar skin is thin, dry,

shiny, depigmented, and yellow-white. The tension of parts often causes cracks,

excoriations, and annoying pruritus.

These atrophic changes must be differentiated from the changes of lichen

sclerosus. Microscopically, the epithelium becomes markedly thinned with a loss

or blunting of the rete ridges. In some cases, there is also a thickening or

hyperkeratosis of the surface layers. Inflammation is usually present. When

lichen sclerosus is present, there is usually a diffuse whitish change to the

vulvar skin. The vulvar skin often appears thin, and there may be scarring and

contracture beyond what is seen with simple estrogen deprivation. In addition,

fissuring of the skin is often present, accompanied by excoriation secondary to

itching. It is nonneoplastic and involves glabrous skin as well as the vulva.

Areas of squamous hyperplasias (formerly called hyperplastic dystrophy without

atypia) also appear as whitish lesions in general, but the tissues of the vulva

usually appear thickened and the process tends to be more focal or multifocal

than diffuse. (The term lichen sclerosus et atrophicus was dropped

because the epithelium is metabolically active, not atrophic.)

Vulvar atypia (formerly leukoplakia) may

present as a slowly progressing, chronic, inflammatory, hypertrophic process

involving the epidermis and subepithelial tissues. It may occur as single or multiple discrete plaques or as a generalized lesion involving the clitoris, prepuce, labia

minora, posterior commissure, perineum, and perianal areas. The lesion is

grayish white in color, thickened, and almost asbestos-like in appearance.

Fissures and ulcerations are common. The histologic picture includes

hyperkeratosis, increase in the stratum granulosum, acanthosis, lymphatic

infiltration of the cutis, and destruction of the elastic fibers of the corium.

Differentiation of this from other lesions of the vulva is important because

squamous cell carcinoma of the vulva is preceded

by these changes in almost 50% of cases.

Prolonged scratching may provoke lichenification, a secondary change in

the skin. The skin has a thickened, leathery appearance in which the normal

markings appear accentuated. When moisture is present, the lesion assumes a

grayish-white, soggy appearance. Hyperkeratosis, parakeratosis, acanthosis, and

prolongation of the retial pegs can be seen histologically, but the subepithelial elastic fibers are not destroyed.