EJACULATORY DUCT OBSTRUCTION

Ejaculatory duct obstruction (EDO) underlies 1% to 5% of male infertility. Although originally described in azoospermic men with complete blockage, it is now clear that EDO is a more complex anatomic condition that can take several forms.

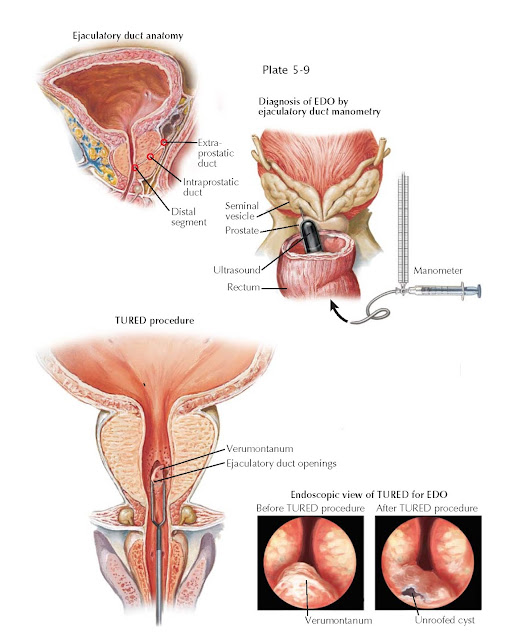

The ejaculatory ducts are paired, collagenous, tubes that commence at the

junction of the ampullary vas deferens and seminal vesicle, course through the

prostate, and empty into the prostatic urethra at the verumontanum. The duct

has three regions: an extraprostatic portion, a middle intraprostatic segment,

and a distal segment within the verumontanum. Ejaculatory continence is

maintained, and urinary reflux prevented, by the acute angle of duct insertion

into the urethra.

Physiologically, the relationship between the seminal vesicle and

ejaculatory duct is similar to that of bladder and urethra. Just as bladder

outlet obstruction can result from prostatic blockage, so too can physical

blockage of the ejaculatory ducts cause EDO. By similar reasoning, “functional”

or neurologic dysfunction of the seminal vesicle may be similar to voiding

dysfunction due to bladder myopathy. At times, a “functional” issue can be

mistaken for “physical” ejaculatory duct blockage, thus adding further

complexity to the diagnosis of EDO.

Ejaculatory duct obstruction presents with infertility, postejaculatory

pain, or hematospermia. Low-volume azoospermia defines complete or classic EDO

and rep- resents the physical blockage of both ducts. Unilateral complete or

bilateral partial physical obstruction results in incomplete or partial EDO.

Both are associated with either one or more of low ejaculate volume,

postejaculatory pain, or hematospermia. However, partial EDO is uniquely

associated with oligoasthenospermia.

Ejaculatory duct obstruction can result from seminal vesicle calculi,

müllerian duct (utricular) or wolffian duct (diverticular) cysts,

postinflammatory scar tissue, medications or medical conditions, calcification,

or congenital ductal atresia. With congenital blockage, genetic evaluation for

cystic fibrosis gene mutations is indicated. Transrectal ultrasound may reveal

dilated seminal vesicles, ejaculatory duct cysts, calculi, absence of the vas,

or müllerian duct remnants. Associated risk factors for EDO include prior

urinary tract infection, epididymitis, perineal trauma, orchalgia, and perineal

pain. It is important to discontinue medications that may impair ejaculation.

Although rare, a digital rectal examination revealing enlarged, palpable

seminal vesicles may suggest EDO.

Procedures used to confirm the diagnosis of EDO include seminal vesicle

sperm aspiration (a normal seminal vesicle should not have sperm in it, unlike

a blocked one), contrast seminovesiculography (injection of contrast in a

manner similar to vasography to locate the obstruction), and seminal vesicle

chromotubation (a variant of vesiculography in which dye is injected and

ejaculatory duct patency assessed visually). A prospective study of these three techniques deemed patency with

chromotubation the most accurate way to diagnose ejaculatory duct obstruction.

Because of the complexity of diagnosing partial EDO, testing has been

developed that can differentiate physical from functional forms of EDO. Similar

to the concept of urodynamics for bladder outlet obstruction, ejaculatory duct

manometry measures the “opening pressures” of the ejaculatory duct, defined as

the pressure above which fluid from the seminal vesicle that passes through the

ejaculatory duct enters the prostatic urethra. Fertile patients have remarkably

consistent and low opening pressures, defined as 45 cm H2O, and infertile men

with EDO have significantly higher ED pressures. Based on the well-established

pressure-flow concept used to evaluate ureteropelvic junction and bladder outlet obstruction, diagnostic ED manometry can differentiate

complete from partial, and physical from functional, forms of EDO.

Once EDO is confirmed diagnostically, the treatment is transurethral

resection of the ejaculatory ducts (TURED), performed in an outpatient setting

under anesthesia. Similar to transurethral prostatic resection for benign

prostatic hypertrophy (see Plate 4-17), the technique combines

cystourethroscopy with resection of the verumontanum in the midline (for complete

obstruction) or laterally (for unilateral obstruction) with cutting current.

When performed correctly, cloudy, milky fluid is usually seen refluxing from the

opened ducts. Postoperatively, a small Foley catheter is placed for 24 hours.

Impressive and durable increases in semen quality are common after the procedure.