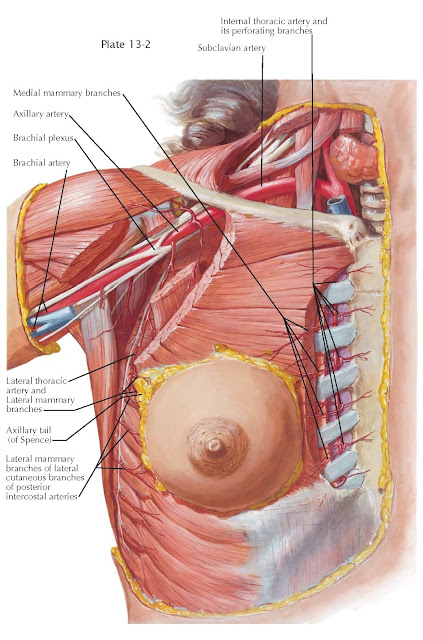

THE BREAST: BLOOD SUPPLY

The sources of the abundant vascular supply of the mammary gland are the descending thoracic aorta, from which the posterior intercostal arteries branch off; the subclavian artery, from which the internal mammary artery arises; and the axillary artery, serving the mammary gland through the lateral thoracic and sometimes through another branch, the external mammary artery. Additional blood may be supplied by branches from the thoracodorsal artery and the thoracoacromial artery, which is a short trunk that arises from the forepart of the axillary artery, its origin being generally overlapped by the upper edge of the pectoralis minor. The intercostal branches of the internal mammary artery, the thoracic portion of which lies behind the cartilage of the six upper ribs just outside the parietal layer of the pleura, supply the medial aspect of the gland. The lateral cutaneous branches of the third, fourth, and fifth aortic intercostal arteries enter the gland laterally. The lateral cutaneous branches of the intercostal arteries penetrate the muscles of the side of the chest and then divide into anterior and posterior rami, of which only the anterior rami reach the mammary gland. The branches from the lateral thoracic artery, which descends along the lower border of the minor pectoral muscle, approach the gland from behind in the region of the upper outer quadrant. One of these branches (in women more developed than the other branches) is the external mammary artery, which turns around the edge of the pectoralis major muscle, where it could be seen in the picture if the breast were lifted up. An extensive network of anastomoses exists between the lateral thoracic artery and those vessels deriving from the internal mammary artery; the latter also anastomoses with the intercostal arteries, so that two or even three of the main sources supply many parts of the gland. The ramifications of all three main arteries form a circular plexus around the areola, which ensures the blood supply of the nipple and areola. The breast skin depends on the subdermal plexus for its blood supply. This plexus is in communication with underlying deeper vessels supplying the breast parenchyma, where a second plexus from the same main vessels is formed in the deeper regions of the gland.

A number of variations of this

vascular distribution exist and should be considered to avoid the danger of

necrosis, for example, in circular incisions around the nipple. The rich blood

supply of the breast allows for a variety of surgical procedures, therapeutic

or cosmetic, to be performed while ensuring the viability of

the skin flaps and breast parenchyma after surgery. This advantage can become a

disadvantage by providing a point of systemic spread for infection or

malignancy.

The veins follow the course of the

arteries. Venous drainage is primarily into the axillary vein, with some blood

draining into the internal thoracic vein. The axillary vein has an irregular

anatomy, which complicates surgery under the arm. The surface veins encircle

the nipple and carry blood to the internal mammary, axillary, and intercostal veins, and to the

lungs. These connections can allow breast cancer cells to travel to the lungs

via these surface veins to form metastatic tumors. The intercostal veins join a

complex network of vertebral veins in and around the spine, providing an

additional path for cancer to spread to bone.

The veins draining the breast

parenchyma are subject to inflammation and thrombosis as in other areas in the

body. This can result in Mondor

disease and thrombophlebitis, respectively.