FUNCTIONAL CHANGES IN GASTRIC

MOTILITY AND SECRETION IN GASTRIC

DISEASES

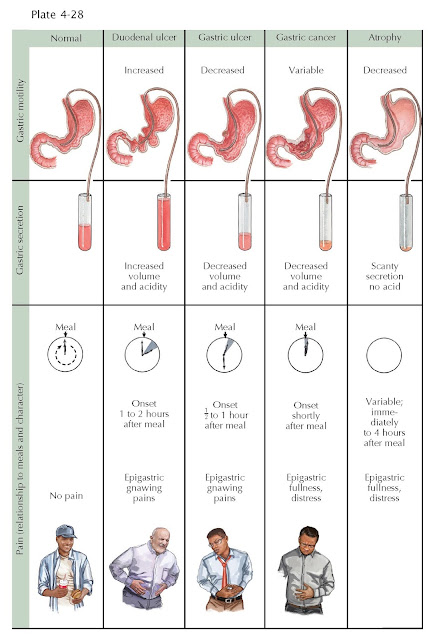

Gastric secretion and motility vary considerably from one individual to another and in the same individual from time to time. In the stomachs of subjects in whom no disease of the upper gastrointestinal tract can be demonstrated, the emptying time of a standard meal may vary over 100% from the average, and the concentration of HCl (acid) secreted in the basal state or in response to the standard stimuli ranges from 0 to 100 mEq/L or more.

A

tendency to gastric hypertonicity and hypermotility is observed in many

duodenal ulcer patients. Initial emptying of a meal may be delayed for a

considerable time because of reflex antral spasm incited from the ulcerated

duodenal bulb; after the pressure by the active contractions of the stomach

overcomes the pyloroantral resistance, evacuation proceeds rapidly, so that the

final emptying time may be considerably shortened. The most important motility

change occurs when the ulcer area becomes inflamed and edematous, or scarred,

so that the gastric outlet is obstructed. After a preliminary period of

hypermotility, the stomach becomes atonic, a condition immediately recognized

roentgenographically with the first swallow of barium. The stomach, in cases of

duodenal ulcer, tends to secrete excessive acid, in both volume and

concentration, so that the average output of acid in duodenal ulcer

patients greatly exceeds the average of all other categories, including the

normal. The rare disease described by Ellison and Zollinger is characterized by

peptic ulceration in the upper intestine distal to the duodenal bulb and

secretion of enormous quantities of gastric acid.

It

is not certain whether hypersecretion exists before the duodenal ulcer starts

to develop, but it does persist after the ulcer heals. This may be due to an

underlying H. pylori infection affecting the inhibitory D cells of the

stomach secreting somatostatin that normally inhibits gastric acid secretion.

The

pain in duodenal ulcer is most often described as a gnawing or intense hunger

sensation, coming on characteristically from 1 to 2 hours after a meal.

The

pathophysiologic phenomena caused by a gastric ulcer depend on the site of the

ulcer in the stomach. The closer the ulcer is to the pylorus, the more the

manifestations resemble those of duodenal ulcer. In peptic ulcer of the lesser

curvature at or proximal to the incisure, gastric motility is not notably

altered from normal, except for some local

hypertonicity of the musculature at, and frequently opposite, the ulcer site.

When the gastric emptying is delayed in a case of ulcer of the body of the

stomach, the presence of a coexisting duodenal ulcer should be suspected. The

gastric stasis resulting from chronic pyloric narrowing by a duodenal ulcer may

be a factor for formation of a gastric ulcer.

The pain of gastric ulcer tends to occur

relatively soon after eating, because the gastric acid content is in immediate

contact with the lesion. For this reason, smoothness and blandness of the diet

are much more important in a gastric than in a duodenal ulcer. Now that proton

pump inhibitors are used in treatment, eating a bland diet has become less

important.

GASTRIC

CANCER

Gastric

carcinoma is not characterized by any general motility pattern, except for the

obvious changes to be expected in an area of infiltration into muscle or where

the tumor produces obstruction.

GASTRIC

ATROPHY

In

atrophy of the gastric mucosa (schematically indicated in the picture by

a flattened mucosal surface, although the thinning of the mucosa by loss of the

normal glandular arrangement does not necessarily result in obliteration of the

rugal folds), the reduction in glandular elements results in greatly

diminished acid secretion and often no HCl secretion even with maximal stimulation.

The reduction of gastric acid results in a secondary elevation of the systemic

hormone gastrin, trying to signal to increase gastric acid secretion. Thus, an

elevated serum gastrin level may be seen in either Zollinger-Ellison syndrome

or pernicious anemia with its gastric atrophy. Differentiation of these two

entails the presence of ulcers in Zollinger-Ellison syndrome or measuring

gastric acidity (low in pernicious anemia but high in Zollinger-Ellison

syndrome). If motility is affected at all in gastric atrophy, it is in the

direction of a decrease.