CONGENITAL MUSCULAR TORTICOLLIS

(WRYNECK)

Congenital muscular torticollis (congenital wryneck) is a common condition, usually discovered in the first 6 to 8 weeks of life. Contracture of the sternocleidomastoid muscle tilts the head toward the involved side, rotating the chin to the contralateral shoulder. The cause is believed to be ischemia of the sternocleido-mastoid muscle, particularly the sternal head, due to intrauterine positioning, prolonged labor, or increased pressure during passage through the birth canal. The contracture usually occurs on the right side, and 20% of children with congenital muscular torticollis also have congenital dysplasia of the hip. These observations support the hypothesis that both problems are related to intrauterine malpositioning or presentation.

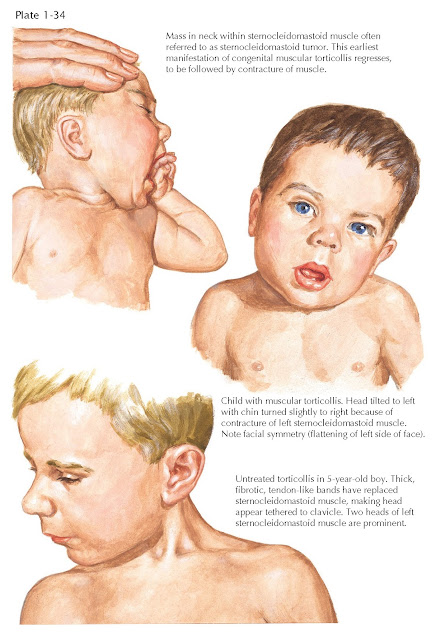

Clinical Manifestations. In the first month

after delivery, a soft, nontender enlargement, or “tumor,” is noted beneath the

skin and attached to the body of the sternocleidomastoid muscle (see Plate 1-34). The tumor

usually resolves in 6 to 12 weeks, after which contracture, or tightness, of

the sternocleidomastoid muscle and the torticollis become apparent. With time,

fibrosis of the sternal head of the muscle may entrap and compromise the branch

of the accessory nerve to the clavicular head, further increasing the

deformity.

|

| CLINICAL APPEARANCE OF CONGENITAL MUSCULAR TORTICOLLIS (WRYNECK) |

If the contracture does not improve, deformities of the face and skull

(plagiocephaly) can develop in the first year. The face becomes flattened on

the side of the contracted sternocleidomastoid muscle. The deformity is related

to the sleeping position. Children who sleep prone are more comfortable with

the affected side down; consequently, that side of the face becomes distorted.

Children who sleep supine develop flattening of the back of the head.

Treatment. In the first year of life, conservative

measures comprising stretching and range-of-motion exercises and positioning

produce good results in 85% to 90% of patients. If conservative measures fail,

surgical intervention is required. Surgery should be considered in patients

with a persistent sternocleidomastoid contracture at age 11 months. Allowing

the deformity to persist results in permanent facial asymmetry, vision

difficulties, and a poor cosmetic result.

Surgery usually consists of resection of a portion of the distal

sternocleidomastoid muscle. The incision should be placed transversely in the

neck to coincide with the normal skin folds. It should not be placed near the

clavicle, because scars in this area tend to spread. Postoperative treatment

includes passive stretching exercises and, occasionally, a brace

or cast to maintain the corrected position.

NONMUSCULAR CAUSES OF TORTICOLLIS

Torticollis is a common childhood complaint that can be caused by a wide

variety of problems, but identifying the cause can be difficult (see Plate

1-35). If the characteristic posture of the head and neck is noted shortly

after birth, congenital anomalies of the cervical spine should be considered,

particularly those of the occipitocervical junction. Torticollis may be a sign of

Klippel-Feil syndrome, basilar impression, or occipitalization of the atlas. In

these conditions, however, the sternocleidomastoid muscle on the short side is

not contracted.

Wryneck that appears several weeks after birth is usually congenital

muscular torticollis. Less commonly, soft tissue problems such as abnormal skin

webs or folds (pterygium coli) maintain the neck in a twisted position. Tumors

in the region of the sternocleidomastoid muscle, such

as cystic hygroma, branchial cleft cysts, and thyroid teratomas, are rare but

must be considered.

Intermittent torticollis can occur in the young child. A seizure-like

condition called benign paroxysmal torticollis of infancy can be the result of

a variety of neurologic causes, including drug intoxication. Similarly, sudden

posturing of the trunk and torticollis associated with gastroesophageal reflux

are often reported.

A major cause of torticollis in older children is bacterial or viral

pharyngitis with involvement of the cervical nodes. Spontaneous atlantoaxial

rotatory subluxation (known as Grisel syndrome) can occur after acute viral or

bacterial pharyngitis and in association with flares of autoimmune disorders.

Surgery in the upper pharynx, such as a tonsillectomy, may also

precipitate rotatory subluxation. Inflammation and local edema in the

retropharyngeal region lead to transient laxity of the ligamentous restraints,

allowing greater motion of C1-2. Standard radiographic techniques are

inadequate for diagnosis, and special views, including tomography and fine cut

CT limited to the upper cervical spine, are often required. Bed rest, NSAIDs,

and use of a soft collar may be sufficient if the diagnosis is made early. A

head halter or halo brace may be necessary for long-standing problems or if the

simple measures fail. If the torticollis persists beyond 3 weeks, recurs, or

becomes subacute, postreduction immobilization in a Minerva cast brace or halo

brace is indicated. Surgical stabilization is required for the rare

recalcitrant cases.

|

| NONMUSCULAR CAUSES OF TORTICOLLIS |

Traumatic causes should be considered and carefully excluded in the

diagnosis of torticollis. Unrecognized and untreated injuries may have serious

neurologic consequences. Torticollis commonly follows an injury to the C1-2

articulation. It may also be due to fractures and dislocations of the dens,

which may not be apparent on initial radiographs. Skeletal dysplasia, Morquio

syndrome, spondyloepiphyseal dysplasia, and Down syndrome are commonly associated

with C1-2 instability and accompanying torticollis.

Torticollis is also a sign of certain neurologic problems, particularly

space-occupying lesions of the central nervous system, such as tumors of the

posterior cranial fossa or the spinal cord, chordoma, and syringomyelia.

Uncommon neurologic causes include dystonia musculorum deformans and hearing

and vision problems, which can lead to head tilt. Although hysterical and

psychogenic causes have been described, they are very uncommon and

should be considered only a diagnosis of exclusion.

Calcification of the vertebral disc, while an uncommon problem of

childhood, most often involves the cervical vertebrae. The C6-7disc space is

the most frequent site, but any disc space can be involved. In 30% of children,

trauma is the apparent cause; 15% of children report an upper respiratory tract

infection. The onset of symptoms is abrupt, with torticollis, neck pain, and

limitation of neck motion the usual presenting complaints. Only 25% of patients

are febrile on presentation. Rarely, the disc herniates posteriorly, causing

spinal cord compression, or anteriorly, causing dysphasia. Typically, the

clinical manifestations resolve rapidly and the radiographic signs more

gradually. Two thirds of children are symptom free within 3 weeks and 95%

within 6 months. Resolution of associated neurologic symptoms

occurs in 90% of patients.