AEROPHAGIA AND BELCHING

Aerophagia is described as objectively observed or measured air swallowing. Aerophagia usually leads to troublesome repetitive belching. These symptoms must occur at least 3 times a week for over 6 months to be considered a functional gastrointestinal disorder by the ROME criteria, a consensus gastrointestinal guideline. Aerophagia with belching is seen more commonly in developmentally disabled or anxious persons but can be seen in any population.

There

are various pathophysiologic mechanisms by which aerophagia occurs. For one, a

person can swallow air and retain it in the esophagus. This can occur voluntarily

or in conditions in which the lower esophageal sphincter remains tight, such as

achalasia. Aerophagia occurs during normal daily activities such as swallowing

saliva; however, it can be exacerbated by certain lifestyle factors such as

rapid ingestion of food, smoking, chewing gum, or drinking carbonated

beverages. Physical activity with deep breathing, mouth breathing, and the use

of a continuous positive airway pressure device can also lead to increased

aerophagia. Hyperventilation when nervous or mouth breathing due to nasal or

sinus disorders also is a common cause.

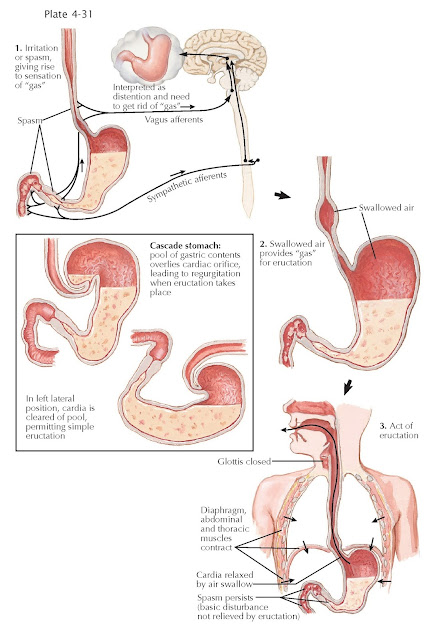

The

consequence of aerophagia is usually belching, also known as burping or

eructation. In the act of belching, the glottis is closed and the diaphragmatic

and thoracic muscles contract when the increased intraabdominal pressure

transmitted to the stomach is sufficient to overcome the resistance of the

cardia and the physiologic lower esophageal sphincter; the swallowed air is

expelled via a burp. Belching can become a chronic disorder with habit-forming

potential.

Belching

occurs from the beginning of life and is frequently seen in infants, who often

swallow air while drinking milk. In adults, belching may occur because of

overdistention of the stomach after a large meal. Certain foods such as

broccoli, beans, cauliflower, and other high-fiber foods can predispose to gas

formation and, in turn, belching. Food substitutes and medications that are

poorly digested may lead to gas and burping. Examples include sorbitol, which

is used frequently as a sugar substitute, and lactulose, which is used in

patients with constipation or hepatic encephalopathy. Inflammation of the

stomach from disorders such as gastritis or peptic ulcer disease can also lead

to stomach discomfort and the need to belch. Lastly, transient lower esophageal

sphincter relaxations that occur spontaneously while a person is upright and

awake can lead to the release of air from the stomach.

The

diagnosis of aerophagia is often made by careful history taking. Repetitive

belching can also be diagnosed by the history, although sophisticated tools

such as esophageal manometry, esophageal impedance, or impedance pH testing may

indicate that it is occurring. An increase in abdominal pressure coupled with

retrograde reflux and subsequent relaxation of the upper esophageal sphincter

signifies belching; other conditions, such as rumination, can also have these

signs, however.

Rarely

does aerophagia or belching lead to worrisome complications. The potential for

gastric volvulus, intestinal ileus, or perforation can theoretically exist with

excessive aerophagia, but they are rare and mainly seen in developmentally

disabled persons. These patients can be challenging because they may not be

able to follow recommendations. In these cases, other measures to

decompress the stomach or colon may be needed. Nasogastric, gastrostomy, or

rectal decompression tubes may be necessary to avert complications. More

commonly, aerophagia and belching are not at all dangerous, and the main

consequences are bothersome symptoms for the patient or his or her family.

Although patients often seek out medical advice for these troublesome symptoms,

they are often relieved to hear that neither condition is life threatening. The

best therapy for aerophagia and belching is education and behavioral modifications.

Investigations for pathologic conditions such as gastroesophageal reflux

disease (GERD) or peptic ulcer disease may be completed but are generally

unhelpful. For individuals who suffer from discomfort from aerophagia,

positional maneuvers can be helpful. Lying on the left lateral side or bringing

the knees up to the chest may help slowly release air without overt belching.

Although their effectiveness has not been proven, other treatment regimens

include reathing exercises, biofeedback therapy, and hypnosis.