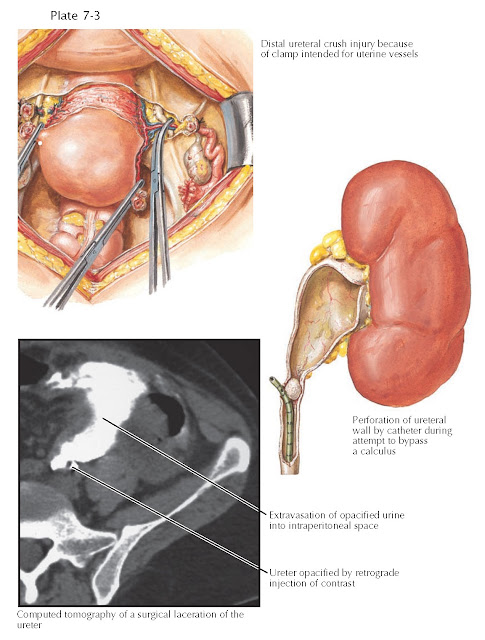

URETERAL INJURIES

The vast majority of ureteral injuries are iatrogenic, occurring during either open pelvic surgery or ureteroscopy. Injuries associated with open surgeries often affect the distal one third of the ureter and go undiagnosed until the postoperative period. The procedures most often implicated are transabdominal hysterectomy and abdominoperineal resection. Fortunately, such complications are rare, with the ureter injured in only 0.5% to 1.0% of all pelvic operations. Injuries incurred during ureteroscopy typically occur during the basketing and attempted removal of ureteral stones.

Ureteral injuries from external trauma are very rare, and more than 95% are related to penetrating wounds. Gunshot wounds account for the vast majority of such injuries; these can either directly rupture the ureter or cause severe contusions secondary to energy from the blast. Blunt injuries account for the remaining 5% of cases and can affect the ureter through several mechanisms. First, a deceleration injury may dislocate the kidney and cause tears at the fixation point of the ureteropelvic junction. In addition, hyperextension injuries of the back may cause avulsion of the ureter as it is stretched against the lower thoracic and lumbar vertebral bodies. This type of injury classically occurs in children struck by motor vehicles.

Successful

surgical management of ureteral injuries requires a high index of suspicion,

early diagnosis, and an intimate knowledge of ureteral anatomy and blood

supply. If recognized and repaired promptly, a ureteral injury is usually

associated with low morbidity. Delayed recognition of ureteral injuries,

however, is common and results in significant morbidity, which can include a

urinoma, stricture (with subsequent hydronephrosis), fistula, abscess, or sepsis.

PRESENTATION

AND DIAGNOSIS

Patients may

complain of flank pain or hematuria, although the latter is not a reliable sign

and is absent in up to 45% of penetrating and 67% of blunt ureteral injuries.

Findings on physical examination may include costovertebral angle tenderness,

flank ecchymosis, and an abdominal mass. In most cases, however, symptoms are

nonspecific. Therefore, clinicians should focus on the patient history and

maintain a low threshold for imaging.

If

intraoperative or blunt injury is suspected, CT with intravenous contrast and

fine cuts through the ureter should be performed to determine the presence and

location of contrast extravasation. Scans must be delayed long enough to

visualize excretion of contrast in the ureter, which usually takes at least 10

minutes.

Although

retrograde pyelography (RPG) is also sensitive enough to reveal most injuries,

it is both time-consuming and cumbersome. Thus RPG has little role in the

acute trauma setting and is reserved for the stable patient with an equivocal

CT scan. If RPG is per- formed, however, it may be possible to treat the

ureteral injury at the same time by deploying a stent.

If there is

a penetrating injury to the peritoneum, surgical exploration is required. The

ureters should be examined for damage using intravenous or retrograde injection

of indigo carmine, which will extravasate at injury sites.

TREATMENT

In patients

who are too unstable to undergo ureteral reconstruction, a “damage control”

approach is appropriate. Two common strategies include bringing the ureter to

the abdominal wall (temporary cutaneous ureterostomy) or ureteral ligation

followed by percutaneous nephrostomy. Definitive reconstruction is delayed until

the patient stabilizes.

In stable

patients, injuries should be explored and repaired.

Ureteral

contusions can lead to strictures if untreated and should thus be stented and

drained. If the contusion is severe, the ureter should be segmentally resected;

debrided until a bleeding edge is reached; reanastomosed tension-free over a

stent; and drained.

Ruptures of

the upper and midureter can be repaired with primary ureteroureterostomy, an

end-to-end anastomosis over a stent. Ruptures of the distal ureter are repaired by reimplanting

the ureter into the bladder (ureteroneocystostomy). If there is extensive loss

of the distal ureter, a section of the bladder is sewn to the ipsilateral psoas

minor tendon (psoas hitch) to help bridge the gap. The ureter is then

reimplanted into the bladder. If the bladder is too small or noncompliant for

stretching, a transureteroureterostomy can be performed, in which the injured

ureter is brought across the midline and sewn to the side of the contralateral

ureter. This procedure is also useful when there are associated rectal, pelvic,

or vascular injuries.

Complex

reconstructions of extensive ureteral injuries may be performed on an elective

basis but are not appropriate for acute management (see Plate 10-36). Such

procedures include ileal interposition, in which the small bowel is used as a

ureteral replacement; Boari flap, in which a section of the bladder is

reconstructed as a tube; and autotransplantation, in which the kidney is relocated to the

ipsilateral pelvis.