THORACOLUMBAR SPINE TRAUMA

Most thoracic and lumbar fractures result from vertical compression or flexion-distraction injuries. These injuries frequently occur around the thoracolumbar junction (T11-L2), because it represents a transition from the stiffer thoracic to the more flexible lumbar spine. The upper thoracic region (T1-10) is more injury resistant because it is stabilized by the ribs, and the lower lumbar region (L3-5) has larger, stronger, and more injury-resistant vertebra.

Multiple classification systems exist for thoracolumbar trauma, but the

three-column theory of Denis is among the simplest to conceptualize (see Plate 1-28). This

concept divides the vertebral body into three columns: the anterior column

extending from the anterior longitudinal ligament through the anterior two

thirds of the vertebral body, the middle column containing the posterior third of

the vertebral body and posterior longitudinal ligament; and the posterior

column, which includes the posterior spinal elements (lamina, pedicles, spinous

processes) and posterior ligamentous complex (supraspinous and interspinous

ligaments, facet capsules, and ligamentum flavum). Injuries involving one

column can frequently be treated nonoperatively, two-column injuries may

require surgical management, and three-column injuries generally mandate

surgical stabilization and fusion.

THREE-COLUMN CONCEPT OF SPINAL STABILITY AND COMPRESSION FRACTURES

COMPRESSION FRACTURES

Compression fractures result from failure of the anterior vertebral

column when a flexion force is applied. This most commonly occurs at the

thoracolumbar junction in elderly patients with osteoporosis. It is

generally a stable fracture, and treatment is usually symptomatic with pain

medication, restricted activity, and a thoracolumbar orthosis for comfort. The

fracture typically becomes stable once the bone heals. Surgical treatment

involves cement augmentation of the vertebral body to provide immediate stability

and to minimize the risk of progressive kyphosis. Multiple compression

fractures in patients with severe osteoporosis can cause a kyphotic,

stooped posture (see Plate 1-28). In such cases, cement augmentation of

the fractured vertebra should be considered.

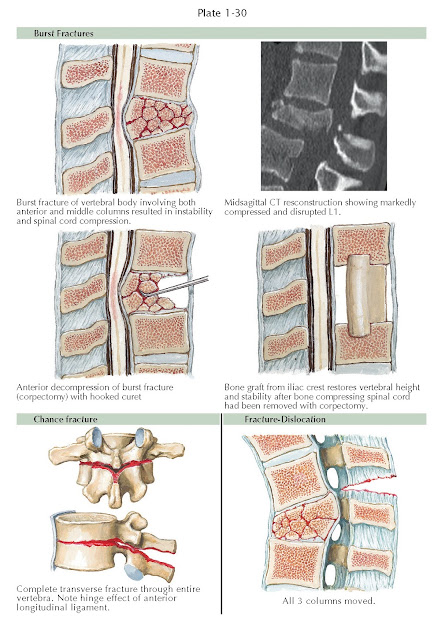

BURST FRACTURES

Burst fractures involve failure of the anterior and middle columns of

the spine from an axial load and are generally associated with higher-energy

trauma than simple

compression fractures. Because the posterior vertebral body (middle column) is

fractured, bony fragments can retropulse into the spinal canal and may cause

spinal cord or nerve root injury (see Plate 1-30). Suspected burst fractures

should be evaluated by CT or MRI to evaluate the degree of spinal canal

compromise and the integrity of the bony and ligamentous structures of the

posterior column. Posterior column injury denotes a more severe fracture

pattern (a “three-column” injury) that frequently requires surgery.

Treatment of burst fractures varies and has been the subject of some

controversy. Stable burst fractures without neurologic injury can be treated

with pain medication, activity restriction, and a thoracolumbar orthosis to

relieve pain and promote bony healing. Relative indications for surgery include

greater than 25 degrees of kyphosis, greater than 50% height loss of the

vertebral body, or greater than 50% spinal canal compromise. A complete or

incomplete neurologic injury and an injury to the posterior column (a

three-column injury) constitute absolute indications for surgery. Surgery

typically involves instrumented spinal fusion two levels above and two levels

below the fractured vertebra. If there is a neurologic injury, then a

decompression is also performed. Posterior-only procedures can be performed

when there is no need for decompression of bony fragments within the spinal

canal, such as when there is no neurologic injury. It can also be performed in

patients requiring decompression with an acute fracture (<5 days after injury)

because such fracture fragments are mobile and can usually be reduced by a

combination of distraction and lordosis. Anterior procedures are appropriate

for subacute injuries requiring decompression, in patients with a

severe neurologic deficit and significant canal intrusion by fracture

fragments, and in patients with severely comminuted vertebral body fractures

with no anterior column support (see Plate 1-30).

COMPRESSION FRACTURES (CONTINUED)

CHANCE FRACTURES

A Chance fracture is typically a bony injury through the vertebra in the

thoracolumbar spine. It is best visualized on the lateral

radiograph or CT scan. The Chance fracture is also known as a “seat belt”

fracture, because it frequently results from motor vehicle accidents in which

the patient wears a lap belt without a shoulder belt. With sudden deceleration,

the patient simultaneously experiences flexion anteriorly, with the lap belt

acting as the pivot point, and distraction (tension) of the posterior column of

the spine. As the distraction continues, a fracture propagates from posterior

to anterior through the spine, involving all three columns (see

Plate 1-30). Although the fracture often reduces

spontaneously, it is inherently unstable. Fractures must be treated surgically

or immobilized in a thoracolumbar orthosis (with spinal stability verified with

a standing radiograph in the brace). Occasionally, this flexion-distraction

injury affects only the discoligamentous structures in the spine, resulting in

a “soft tissue Chance” injury. In this variant of the injury, the transverse

cleavage plain propagates through the posterior ligamentous complex

(supraspinous and interspinous ligaments, ligamentum flavum, and facet

capsules) and anteriorly through the intervertebral disc. Signs of this injury

on the lateral radiograph include gapping at the facet joint and widening of

the distance between spinous processes. This injury must be treated by spinal

fusion because these discoligamentous structures will not spontaneously heal

after being disrupted.

BURST, CHANCE, AND UNSTABLE FRACTURES

UNSTABLE INJURIES OF THE THORACOLUMBAR SPINE

The thoracolumbar junction is vulnerable to several different mechanisms

of injury: flexion, rotation, axial loading, or any combination of those

forces. Fracture- dislocations are relatively common in this region, where the

less mobile thoracic spine meets the highly mobile segments of the lumbar

spine. A fracture-dislocation of the thoracolumbar spine is severe and involves

disruption of all three columns of the spine (see Plate 1-30). These fractures

are inherently unstable and are associated with a high rate of neurologic

injury. Treatment of these injuries typically involves instrumented spinal

fusion and is directed at restoring stability to this area.

SACRAL FRACTURES

Traumatic sacral fractures can present as a solitary injury but often

are observed in association with a pelvic ring or lumbosacral facet injuries in

a patient with multiple injuries. The closer the fracture is to the

midline (either involving the sacral neural foramina or central canal), the

higher is the rate of neurologic injury. Most sacral fractures are stable and

do not require surgery. In patients with neurologic injury and objective

evidence of neurologic compression, however, surgical decompression and

stabilization may be indicated.