THE EXTERNAL

DEVELOPMENT OF THE BRAIN IN THE SECOND AND THIRD TRIMESTERS

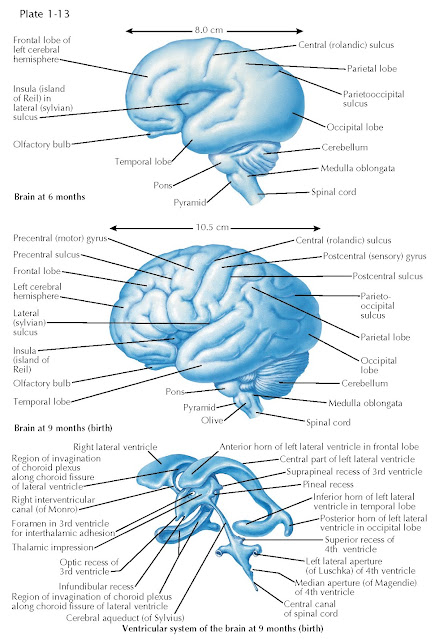

By sixth month of gestation, the cerebral hemispheres acquire several features that prefigure the division of the cortical surface into specific functional regions. Accordingly, one recognizes four distinct domains, or lobes, that define cortical territories. The frontal lobe is most anterior; it eventually includes cortical areas devoted to motor control, language production (left hemisphere only in most individuals), and executive function—the capacity, moment by moment, to integrate perceptions of external stimuli with internal representations of motivations, goals, and memories to plan appropriate complex behavioral responses. Midway along the anterior-posterior axis, the central (also known as the rolandic) sulcus divides the frontal and more posterior parietal lobe, which mediates somatosensation and attention. This anatomic landmark is one of the earliest local furrowings that defines the sulci (grooves) and gyri (bulges) that reflect the elaborate folding of the mature cerebral cortex.

The central sulcus defines two

essential functional regions. On the anterior bank

is the precentral gyrus, the location of the primary motor cortex. Neurons

of the primary motor cortex send axons directly to brainstem and spinal cord

motor neurons that innervate muscles or to interneurons adjacent to these motor

neurons. On the posterior bank is the postcentral gyrus, the location of

the primary somatosensory cortex. The primary somatosensory cortex

receives topographically mapped inputs from brainstem and spinal cord sensory

relay nuclei that represent somatosensory information from the entire body

surface. The remainder of the parietal lobe is devoted to sensory integration

and attention. Posterior and ventral, marked by the parieto-occipital

sulcus, is the occipital lobe, devoted exclusively to representation

and processing of vision. Finally, the anterior medial extension of the

hemisphere defines the temporal lobe, anterior to the lateral sulcus,

including cortical regions that integrate information about the identity of

visual stimuli, auditory information, and, in the left hemisphere only of most

individuals, the representation of “lexical” language (the brain’s “dictionary”

of words). The initial growth of the frontal, parietal, occipital, and temporal

lobes results in “operculation,” or covering of one region of cortical tissue

called the insula. The cortex of the insula becomes specialized for

visceral and homeostatic control and the representation of taste information.

The dramatic growth of the cerebral

hemispheres is accompanied by differentiation of the cerebellum and medulla. By

the end of the sixth month of gestation, the cerebellum expands with furrows

and ridges that eventually become the highly folded folia of the cerebellar

cortex (note: a cortex is the outer sheet of cells that invests any organ). The

pons is distinct, consisting of axons from the cortex that project to pontine

nuclei that then send axons to the cerebellar cortex. The medulla also becomes

furrowed and ridged, but for a different reason. The pyramid, a

prominent ridge on the anterior/ medial medulla is formed by growth of axons

from motor cortical neurons to the brainstem and spinal cord. By the end of

gestation, the pyramid is adjacent to a more lateral ridge, the olive. The

olive reflects accumulation of neurons into the olivary nucleus; olivary

neurons selectively innervate the extensive dendritic arbors of Purkinje cells.

Finally, further elaboration of the

ventricular system accompanies these morphogenetic transformations.

The ventricular system is best

depicted as a “cast” of space within the brain and spinal cord (neural tissue

is absent). The key changes reflect differential growth of brain regions that

correspond to each ventricular division. The lateral ventricles grow

disproportionately and acquire further anatomic definition. The anterior

horn extends into the frontal lobe, with the caudate nucleus of the basal

ganglia as its floor. The inferior horn extends into the temporal lobe;

on its anterior and medial surface is the hippocampus. Finally, the posterior

horn extends into the occipital lobe. The

remainder of the ventricular system is comprised of the same subdivisions

that emerge in the second trimester; however, their shape and size change

substantially. The third ventricle becomes a narrow midline space, further

indented by the thalamus on each side (the thalamic impression) as well

as a foramen surrounding the intrathalamic adhesion. In addition,

the third ventricle is indented by the optic chiasm at the optic recess, the

pineal gland at the pineal and suprapineal recess, and

the pituitary gland at the infundibular recess.