RENAL CELL CARCINOMA

Renal cell carcinomas (RCC) account for a vast majority of primary malignant renal tumors. Approximately 55,000 new cases are diagnosed in the United States each year, and about one third of patients have meta- static disease. Other, less common malignant renal tumors include transitional cell carcinomas of the renal pelvis (see Plate 9-9) and primary renal sarcomas. The kidneys may also contain metastases from extrarenal solid and hematologic tumors.

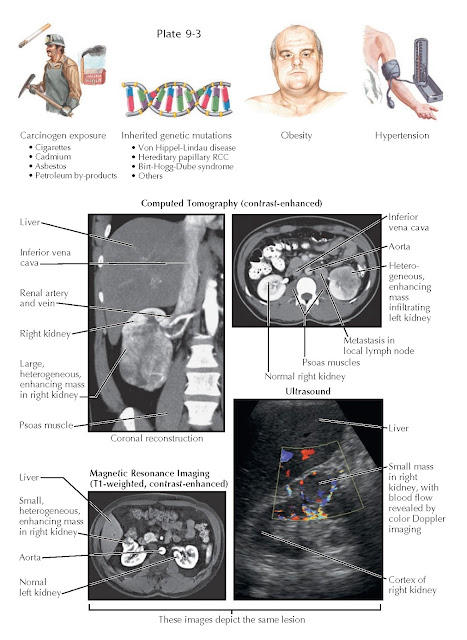

RISK FACTORS AND RADIOGRAPHIC FINDINGS OF RENAL CELL CARCINOMA

EPIDEMIOLOGY

AND RISK FACTORS

RCC was once

more than twice as common among men than among women, although this gap

currently appears to be shrinking. The peak incidence is in the sixth to

seventh decades of life. Environmental risk factors include cigarette smoking

and exposure to cadmium, asbestos, or petroleum byproducts. Data suggest that

cigarette smoking and cadmium exposure each double the risk, and that smoking

alone is responsible for one third of total cases. In addition, genetic

abnormalities in critical tumor suppressor genes and oncogenes are known to

play a key role. Such mutations can be sporadic or part of a hereditary condition,

such as von Hippel-Lindau disease, hereditary papillary RCC, and Birt-Hogg-Dube

syndrome. Hypertension and obesity also increase the risk for RCC, although the

mechanisms are not known. Although many tumors occur in patients without known

risk factors, it is likely that a significant number of “sporadic” cases will

eventually be found to have a genetic basis.

PRESENTATION,

DIAGNOSIS, AND STAGING

In the past,

an RCC was typically not detected until it became symptomatic, usually as the

classic triad of gross hematuria, flank pain, and a palpable mass. In

contemporary practice, however, the classic triad is seen in fewer than 10% of

patients. Instead, the majority of renal masses are now incidentally detected

during abdominal imaging.

Nonetheless,

an RCC may also cause a variety of nonspecific symptoms, including weight loss,

fever, night sweats, and lymphadenopathy. Some patients may also have dyspnea,

cough, and bone pain, which are suggestive of metastatic disease. Finally, RCC

can also be associated with a wide variety of paraneoplastic phenomena,

including erythrocytosis, anemia, hypercalcemia, hypertension, and

nonmetastatic hepatic dysfunction (Stauffer syndrome). Patients with any

combination of these symptoms or syndromes require immediate evaluation for

possible RCC.

The

evaluation of a known or suspected RCC begins with a thorough history and physical examination, with careful attention to the

symptoms listed previously. On laboratory assessment, possible abnormalities

include abnormal hematocrit, elevated erythrocyte sedimentation rate, elevated

serum calcium concentration, and abnormal liver function tests. Finally, a

careful evaluation of kidney function is important because it may have a

significant impact on the type of management if RCC is diagnosed. A normal serum

creatinine concentration is an acceptable assessment of renal function in

patients with no comorbidities

and normal-appearing kidneys on standard axial imaging. In patients with

medical conditions that predispose to renal disease, such as hyper-tension and

diabetes mellitus, assessing the function of each kidney with a nuclear scan

may be helpful for deciding between radical and nephron-sparing approaches.

Several

imaging techniques may be used to evaluate a suspected RCC, including

ultrasound (US), computed tomography (CT),

magnetic resonance imaging (MRI), renal angiography, and radionuclide imaging

(renography).

CT scan is

the most frequently employed modality because it has a high sensitivity for

detecting renal masses and is the most accurate. Any renal mass that enhances

with contrast is potentially malignant. CT also provides excellent

visualization of the adjacent structures into which the primary tumor can

extend or metastasize—such as the renal vein, regional lymph nodes, inferior

vena cava, and suprarenal (adrenal) glands—which enables accurate staging.

Ultrasound

can help identify the presence of a renal mass. Although ultrasound evaluation

does not require ionizing radiation and is less expensive than CT, it is less

sensitive and is highly dependent on operator skill. MRI is as sensitive as

CT and is the study of choice for patients who cannot receive iodinated

contrast.

The most

common sites for metastasis of renal cell carcinoma include the local and

thoracic lymph nodes, lungs, liver, bone, brain, ipsilateral suprarenal gland,

and contralateral kidney. Thus metastatic evaluation should include a chest

radiograph/CT scan and liver function tests. Bone scans may be indicated if the

patient complains of musculoskeletal pain, or if the serum calcium or alkaline

phosphatase concentrations are elevated.

Renal tumors

are generally not biopsied because of concerns regarding complications, the

false-negative result rates, and the fact that an overwhelming majority (90%)

of renal masses greater than 4 cm in diameter are malignant. In contemporary

practice, with more small renal tumors (4 cm) being identified, the role of

renal biopsy is actively being reevaluated, and it is likely that in the future

renal biopsy will become a more common practice. Potential complications

include bleeding, infection, needle track seeding, and pneumothorax. In

addition, false negatives for malignancy do occur.

GROSS PATHOLOGIC FINDINGS IN RENAL CELL CARCINOMA

TREATMENT

The optimal

treatment of RCC depends largely on the tumor stage, size, and location, as

well as the patient’s overall clinical condition.

Localized

disease can be surgically treated with radical resection (see Plate 10-19),

nephron-sparing surgery (such as partial nephrectomy [see Plate 10-22] or

ablation [see Plate 10-24]), or observation with an active surveillance

protocol. In contrast, unresectable or metastatic RCC in patients with good

functional status is

commonly managed with initial cytoreductive surgery followed by systemic

medications, such as interleukin 2 and tyrosine kinase inhibitors. In patients

with poor functional status, medical therapy alone is used.

Localized

Disease. Radical nephrectomy was previously the initial standard of care for the

treatment of all localized RCCs. The operation involves complete removal of the

kidney and suprarenal (adrenal) gland within the renal fascia, as well as

removal of regional lymph nodes from the crus of the diaphragm to the aortic

bifurcation. The surgery can be performed using either an open or laparoscopic approach and results in

an extremely low local recurrence rate (2% to 3%). Laparoscopic radical

nephrectomy, however, has become increasingly popular in recent years because

of shorter recovery times and equivalent oncologic outcomes when compared with

the open approach. Thus

it is now considered the treatment of choice for patients with localized tumors

less than 10 cm in diameter with no local invasion, renal vein involvement, or lymph node metastasis.

Partial nephrectomy is an alternative to

radical resection that preserves renal function in the affected kidney. The

procedure can be performed using either an open or laparoscopic approach. In recent years, partial nephrectomy has

become the standard of care for patients with tumors that are fewer than 4 cm

in diameter. This option can be especially important in patients with decreased

renal function, a solitary kidney, or a chronic disease that may affect

long-term renal function. Careful preoperative and intraoperative imaging is

required to adequately identify the tumor’s borders and its relationship to

major intrarenal vessels and the collecting system.

Ablative

procedures, including cryosurgery and radiofrequency ablation, are newer

nephron-sparing techniques that have been studied as alternatives to partial

nephrectomy. These techniques can be per- formed from either a percutaneous or

laparoscopic approach, and they are associated with shorter recovery times and

decreased morbidity. Successful treatment requires adequate intraoperative

imaging to ensure optimal placement of the ablation probes, as well as

repetitive ablative cycles to ensure complete tumor destruction. Although these

procedures are safe and well-tolerated, long-term oncologic data are still

relatively limited. The preliminary data, however, demonstrate that recurrence

rates may be slightly higher than those following traditional surgery.

Nonetheless, ablative techniques are useful options for many patients,

including those with contraindications to conventional surgery, those with

multiple lesions (in whom partial nephrectomy would be difficult), or those with

recurrent disease that requires focal salvage therapy.

In patients

who are elderly or are poor candidates for surgery for other reasons,

observation is a reasonable alternative. It is generally reserved for patients

with small (3 cm) renal lesions. There is no established standardized protocol

for active surveillance; however, most clinicians perform serial imaging every

6 to 12 months to assess for disease progression.

|

| HISTOPATHOLOGIC FINDINGS IN RENAL CELL CARCINOMA |

Metastatic

Disease. In the past, patients with advanced RCC were not viewed as candidates

for surgical resection, given their poor prognosis. Recently, however,

advancements in adjuvant therapies have changed the role of surgery in the

management of metastatic disease. In patients with good performance status and

limited metastatic disease, the goal of surgical resection is to completely

remove all affected tissue, including nearby organs and/or abdominal wall muscles. In addition,

careful removal of solitary metastases has been shown to improve 5-year

survival rates in some patients. Such interventions are cytoreductive and have

been shown to improve outcomes if performed before the initiation of adjuvant

therapy.

Several

biologic agents have been recently developed and studied as treatment for

disseminated clear cell RCC. Tyrosine kinase inhibitors, such as sorafenib and sunitinib, have been

found to inhibit tumor growth and angiogenesis by blocking the vascular

endothelial growth factor receptor (VEGF-R). Meanwhile, bevacizumab is an

monoclonal antibody that has also been shown to be effective, and which acts by

directly binding circulating VEGF. Additional agents with proven efficacy

include mTOR (mammalian target of rapamycin) inhibitors, such as temsirolimus

and everolimus. Finally, high-dose interleukin 2 (IL-2) can activate an immune response against the tumor, with modest response rates. The effect of

these various agents on the growth and overall prognosis of non–clear cell

tumors is unclear and remains under active investigation.

PATHOLOGY/GRADING

There are

several variants of RCC, which are distinguished based on histomorphology. In

addition, there are cytogenetic abnormalities that correlate with the

histologic findings. Renal cell carcinoma variants include clear cell (75% to

85%, arising from the proximal tubule), papillary (15%, also arising from the

proximal tubule, sometimes termed chromophil), chromophobe (5%, arising from

intercalated cells of the cortical collecting duct), unclassified (5%),

multilocular clear cell (rare), renal medullary (rare), Xp11 translocation

(rare), mucinous tubular, spindle cell (rare), and collecting duct (rare). The

histologic features of the most common tumor types are shown in Plate 9-5.

For clear

cell carcinomas, the Fuhrman nuclear grading system has prognostic significance

and should always be used; it grades these tumors from 1 to 4 based on nucleus

size, nucleus shape, and nucleolus appearance. The use of this grading system

in non–clear cell carcinomas is less well established.

PROGNOSIS

The

prognosis of treated RCC depends on numerous variables, including tumor stage,

histopathologic findings, presence or absence of symptoms, laboratory values,

and the patient’s overall performance status. The tumor stage is the most

significant factor, since the 5-year survival of a TNM stage I tumor has been

found to be approximately 95%, whereas that of a stage IV tumor is less than

25%. Several scoring systems have been devised to calculate the overall

prognosis based on various factors.

STAGING SYSTEM AND SITES OF METASTASIS IN RENAL CELL CARCINOMA

FOLLOW-UP

Although

there is no standard recommendation for follow-up of patients who have

undergone surgical resection of localized RCC, the frequency and intensity of

the protocol are generally dictated by the clinical tumor stage,

histopathology, and treatment strategy. Patients are at greatest risk for recurrence in the first 5 years.

Many centers

determine their follow-up schedule based on tumor stage. Patients with

localized tumors that are less than 7 cm in diameter (T1) are at lowest risk

for recurrence. Such patients should undergo annual evaluation that consists of

a physical examination, chest radiograph, and laboratory testing of liver and

kidney function. Some experts recommend measurement of serum alkaline

phosphatase concentrations to monitor for bone metastases; however, the sensitivity and specificity

of this laboratory marker are poor.

Patients

with masses that are larger than 7 cm or extend into adjacent structures (T2-4)

are at higher risk for recurrence and, in addition to the above, should also

undergo annual CT scan. Finally, all patients who have undergone a

nephron-sparing procedure require an additional CT scan 3 months after the

procedure to evaluate the tumor resection site for local disease recurrence.