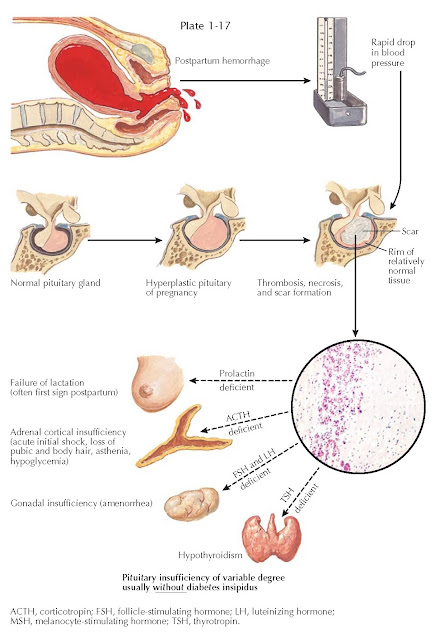

POSTPARTUM PITUITARY INFARCTION (SHEEHAN SYNDROME)

The pituitary gland enlarges during pregnancy (primarily because of lactotroph hyperplasia) and because of its portal venous blood supply is uniquely vulnerable to changes in arterial blood pressure. In 1937, Sheehan suggested that in the setting of severe postpartum uterine hemorrhage, spasm of the infundibular arteries, which are drained by the hypophysial portal vessels, could result in pituitary infarction. If the lack of blood flow continued for several hours, most of the tissues of the anterior pituitary gland infarcted; when blood finally started to flow, stasis and thrombosis occurred in the stalk and the adenohypophysis. The necrotic areas of the adenohypophysis underwent organization and formed a fibrous scar. Sheehan speculated that variations in the extent and duration of the spasm account for variations in the extent of the necrosis. Today it is recognized that the basic mechanism is infarction secondary to a lack of blood flow to the adenohypophysis. However, it is actually not clear if the infarction is a result of vasospasm, thrombosis, or vascular compression.

In about half of postpartum

pituitary infarction cases, the process involves approximately 97% of the

anterior lobe, but the pars tuberalis and a small portion of the superior

surface of the adenohypophysis are preserved. This remnant retains its

structural connections with the hypothalamus and receives portal blood supply

from the neural portion of the stalk. Another type of anterior lobe remnant

that is sometimes found in these cases is a small area of parenchyma at the

lateral pole of the gland without vascular or neural connections with the stalk

and hypothalamus. In other instances, a thin layer of parenchyma remains up

against the wall of the sella under the capsule. Presumably, these peripheral

remnants are nourished by a small capsular blood supply. Normal pituitary

function can be maintained by approximately 50% of the gland, but partial and

complete anterior pituitary failure results in losses of 75% and 90%,

respectively, of the adenohypophysis cells. If more than 30% of the gland is

preserved, there is usually sufficient function to forestall the development of

acute pituitary failure.

The clinical presentation may range

from hypovolemic shock (associated with both the uterine hemorrhage and

glucocorticoid deficiency) to gradual onset of partial to complete anterior

pituitary insufficiency, only recognized when the patient is unable to

breastfeed and has postpartum amenorrhea. These patients may have all of the

signs and symptoms of partial or complete hypopituitarism (see Plates 1-15 and

1-16). The acute loss of glucocorticoids can be fatal if not recognized. These

patients require lifelong pituitary target gland replacement therapy. Diabetes

insipidus in this setting is rare.

Sheehan syndrome should be suspected

in women who have a history of postpartum hemorrhage—severe enough to require

blood transfusion—and who develop postpartum lethargy, anorexia, weight loss,

inability to lactate, amenorrhea, or loss of axillary and pubic hair. The

evaluation involves measuring blood concentrations of the pituitary-dependent

target hormones— 8 am cortisol, free thyroxine, prolactin, estradiol, and

insulinlike growth factor 1. Sheehan syndrome is one of the few conditions in

which hypoprolactinemia may be found. Magnetic resonance imaging shows evidence

of ischemic infarct in the pituitary gland with enlargement followed by gradual

shrinkage over several months and eventual pituitary atrophy and the appearance

of an empty sella.

Because of the improvements in

obstetric care, Sheehan syndrome is no longer the most common cause of

postpartum hypopituitarism. Lymphocytic hypophysitis is the most common cause

of postpartum pituitary dysfunction (see Plate 1-12).

Very rarely, a normal nonparturient

pituitary may become infarcted

in association with hemorrhagic shock.