OBSTRUCTIVE UROPATHY

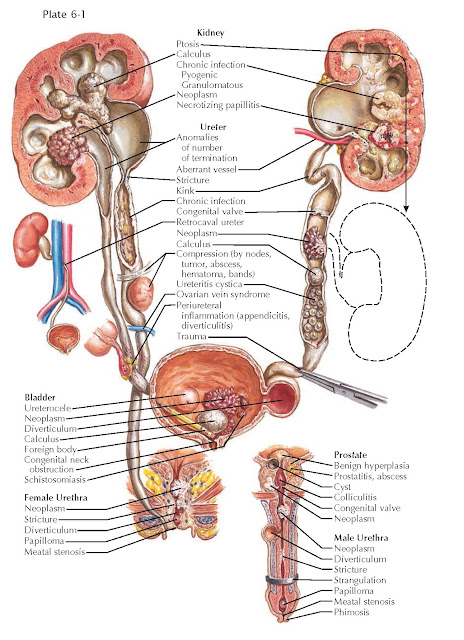

Obstructive uropathy encompasses the numerous sequelae that may be observed when there is an anatomic or functional blockage of the natural flow of urine. Obstructions may occur at any level in the urinary tract, and the clinical signs and symptoms often provide information about both location and severity.

Obstructions may be classified as congenital or

acquired, acute or chronic, partial or complete, and intrinsic or extrinsic.

All of these characteristics must be taken into consideration when deciding on

the optimal treatment plan.

ETIOLOGY OF OBSTRUCTIVE UROPATHY

PATHOPHYSIOLOGY

Congenital obstruction may occur secondary to numerous

abnormalities in normal urinary tract anatomy, including congenital urethral

meatal stenosis, posterior urethral valves (in boys, see Plate 2-34),

ureterocele (see Plate 2-26), ectopic ureter (see Plate 2-25), and

ureteropelvic junction obstruction (see Plate 6-6). In addition, a congenital

spinal dysraphism, such as myelomeningocele or sacral agenesis, may result in

bladder dysfunction and functional obstruction.

Acquired obstructions may occur secondary to numerous

different phenomena, either intrinsic (i.e., within the ureteral lumen) or

extrinsic. In the upper tract (i.e., the kidneys and ureters), the numerous

causes of intrinsic obstruction include nephrolithiasis (see Plate 6-3),

ureteral strictures (see Plate 6-7), tumors (Plate 9-9), polyps, blood clots,

and fungal balls. The numerous causes of extrinsic obstruction include

retrocaval ureter (see Plate 2-19), retroperitoneal fibrosis, retroperitoneal

hematoma, primary retroperitoneal tumor, pelvic lymphadenopathy, and pregnancy.

A functional, rather than structural, obstruction may occur secondary to a

nonperistaltic segment of ureter, as seen in some ureteropelvic junction (UPJ)

or ureterovesical junction (UVJ) obstructions. In the lower tract (i.e., the

bladder and urethra), common causes of intrinsic obstruction include urethral

stricture, urethral diverticulum, foreign body, benign prostatic hyperplasia

(BPH), prostate cancer, primary bladder neck dysfunction, bladder neck

contracture, and bladder cancer. Meanwhile, extrinsic compression may occur

secondary to local extension of cancers in adjacent organs (e.g., cervical,

uterine). A functional obstruction may result from neuropathic bladder

dysfunction (see Plate 8-2).

An obstruction has numerous effects on the urinary system, beginning with compensation and ending with

symptomatic decompensation.

In the upper tract, compensation involves thickening

of ureteral smooth muscle to increase the strength of peristaltic waves against the obstruction. In

addition, there is dilation proximal to the obstruction, which is called

hydronephrosis if it involves the kidney, or hydroureteronephrosis if it

involves both the kidney and ureter. The degree of hydronephrosis is determined

by the location, degree, and duration of the obstruction. The renal pelvis

becomes dilated first, followed by dilation of the calyces. The calyces lose

their normal concave shape and become blunted.

Decompensation occurs as the ureter lengthens and

becomes tortuous, followed by replacement of normal ureteral muscle with scar

tissue. As a result, the ureter progressively loses its ability to contract and

transport a bolus of urine. In the kidney, pressure from the obstruction is

ultimately transmitted to the renal tubules, which leads to reflex

vasoconstriction and reduction of renal blood flow. The glomerular filtration

rate is thus reduced in the obstructed nephrons. If bilateral, these changes may be associated with acute kidney injury. In

chronic, unrelieved obstruction, there may be irreversible atrophic changes in

the renal cortex resulting from chronic ischemia and inflammation.

In the lower tract, compensation involves hypertrophy

of the detrusor muscle in an attempt to overcome the obstruction. Chronic

hypertrophy, however, can lead to trabeculations, cellules, and diverticula.

Trabeculations are interwoven bundles of hypertrophied detrusor muscle that

replace the smooth surface of a normal bladder. Cellules are small pockets of

mucosa that have herniated between the most superficial strands of detrusor

muscle. Diverticula are more pronounced outpouchings that push through all of

the detrusor muscle layers. Because there is no contractile force around the

walls of diverticula, they are unable to effectively eliminate urine, which may

promote formation of bladder stones.

Decompensation occurs as the bladder wall further

deteriorates and becomes diffusely replaced with scar tissue. As a result, the

bladder is unable to properly contract. The high pressure within the bladder

lumen may overwhelm the ureterovesical junctions, causing a secondary reflux

that transmits high pressure to the upper tract.

SEQUELAE OF URINARY TRACT OBSTRUCTION

PRESENTATION AND DIAGNOSIS

Numerous symptoms may signal the presence of a urinary

tract obstruction. In the upper tract, flank pain may occur secondary to

increased stretching of the renal capsule. In the case of an impacted ureteral

stone, additional symptoms include hematuria, nausea, and vomiting, as well as

systemic symptoms if bacteriuria or bacteremia is present. In the lower tract,

outlet obstruction may cause urinary frequency and urgency, low abdominal pain

(caused by bladder spasms), and penile/urethral pain in males. Over time,

urinary hesitancy and a decrease in the force of the stream may occur as the

bladder loses its contractile strength. Finally, complete urinary retention may

occur, leading to stasis, infection, bladder stone formation, and over- flow

incontinence.

The most important tools for diagnosis are the history

and physical examination; however, numerous imaging techniques are often used

to confirm and further characterize the obstruction. Nonfunctional imaging

studies include non contrast computed tomography (CT), renal sonography,

retrograde pyelogram, retrograde urethrogram, and cystography. These tests can

determine the anatomic location of the blockage but cannot assess function.

Functional imaging studies include contrast-enhanced CT, radionucli e studies, intravenous pyelography, and urodynamics.

More invasive tests such as cystoscopy, ureteroscopy, and nephroscopy allow clinicians to make diagnoses under direct vision

and simultaneously perform therapeutic interventions. These tests, however, do

not provide any functional information.

Acute decompression of the urinary tract may be

accomplished using transient interventions, such as placement of a Foley catheter,

suprapubic tube, ureteral stent, or percutaneous nephrostomy tube. Depending on the level and

cause of obstruction, definitive therapy may require surgical intervention, such

as a transurethral outlet surgery (e.g., urethrotomy, prostate incision or

resection), ureteral surgery (e.g., incision, balloon dilation, ureteroscopy),

or abdominal surgery (e.g., ureteropelvic junction obstruction repair, removal

of retroperitoneal tumor).