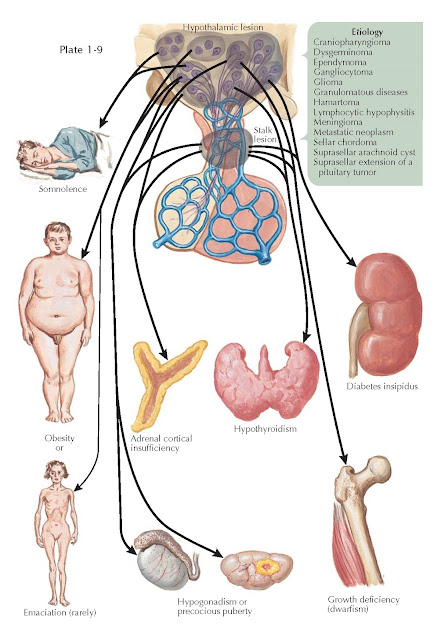

MANIFESTATIONS OF SUPRASELLAR DISEASE

Suprasellar lesions that may lead to hypothalamic dysfunction include craniopharyngioma, dysgerminoma, granulomatous diseases (e.g., sarcoidosis, tuberculosis, Langerhans cell histiocytosis), lymphocytic hypophysitis, metastatic neoplasm, suprasellar extension of a pituitary tumor, glioma (e.g., hypothalamic, third ventricle, optic nerve), sellar chordoma, meningioma, hamartoma, gangliocytoma, suprasellar arachnoid cyst, and ependymoma.

Endocrine and nonendocrine sequelae

are related to hypothalamic mass lesions. Because of the proximity to the optic

chiasm, hypothalamic lesions are frequently associated with vision loss. An

enlarging hypothalamic mass may also cause headaches and recurrent emesis. The

hypothalamus is responsible for many homeostatic functions such as appetite

control, the sleep–wake cycle, water metabolism, temperature regulation,

anterior pituitary function, circadian rhythms, and inputs to the

parasympathetic and sympathetic nervous systems. The clinical presentation is

more dependent on the location within the hypothalamus than on the pathologic

process. Mass lesions may affect only one or all of the four regions of the

hypothalamus (from anterior to posterior: preoptic, supraoptic, tuberal, and

mammary regions) or one or all of the three zones (from midline to lateral:

periventricular, medial, and lateral zones). For example, hypersomnolence is a

symptom associated with damage to the posterior hypothalamus (mammary region)

where the rostral portion of the ascending reticular activating system is

located. Patients with lesions in the anterior (preoptic) hypothalamus may

present with hyperactivity and insomnia, alterations in the sleep–wake cycle

(e.g., nighttime hyperactivity and daytime sleepiness), or dysthermia (acute

hyperthermia or chronic hypothermia).

The appetite center is located in

the ventromedial hypothalamus, and the satiety center is localized to the

medial hypothalamus. Destructive lesions involving the more centrally located

satiety center lead to hyperphagia and obesity, a relatively common

presentation for patients with a hypothalamic mass. Destructive lesions of both

of the more laterally located feeding centers may lead to hypophagia, weight

loss, and cachexia.

Destruction of the vasopressin-producing

magnocellular neurons in the supraoptic and paraventricular nuclei in the

tuberal region of the hypothalamus results in central diabetes insipidus (DI)

(see Plate 1-27). In addition, DI may be caused by lesions (e.g., high

pituitary stalk lesions) that interrupt the transport of vasopressin through

the magnocellular axons that terminate in the pituitary stalk and posterior

pituitary. Polydipsia and hypodipsia are associated with damage to central

osmoreceptors located in anterior medial and anterior lateral preoptic regions.

The impaired thirst mechanism results in dehydration and hypernatremia.

Anterior pituitary function control

emanates primarily from the arcuate nucleus in the tuberal region of the

hypothalamus. Thus, lesions that involve the floor of the third ventricle and

median eminence frequently result in varying degrees of anterior pituitary

dysfunction (e.g., secondary hypothyroidism, secondary adrenal insufficiency, secondary hypogonadism, and growth

hormone deficiency).

Hypothalamic hamartomas,

gangliocytomas, and germ cell tumors may produce peptides normally secreted by

the hypothalamus. Thus, patients may present with endocrine hyperfunction

syndromes such as precocious puberty with gonadotropin-releasing hormone

expression by hamartomas; acromegaly or Cushing syndrome with growth

hormone–releasing hormone expression or

corticotropin-releasing hormone expression, respectively, by hypothalamic

gangliocytomas; and precocious puberty with -human chorionic gonadotropin

(-hCG) expression by suprasellar germ cell tumors.

Because of the close microanatomic

continuity of the hypothalamic regions and zones, patients with suprasellar

disease typically present with not ne but many of the

dysfunction syndromes discussed.