INTRACRANIAL

HEMORRHAGE IN THE NEWBORN

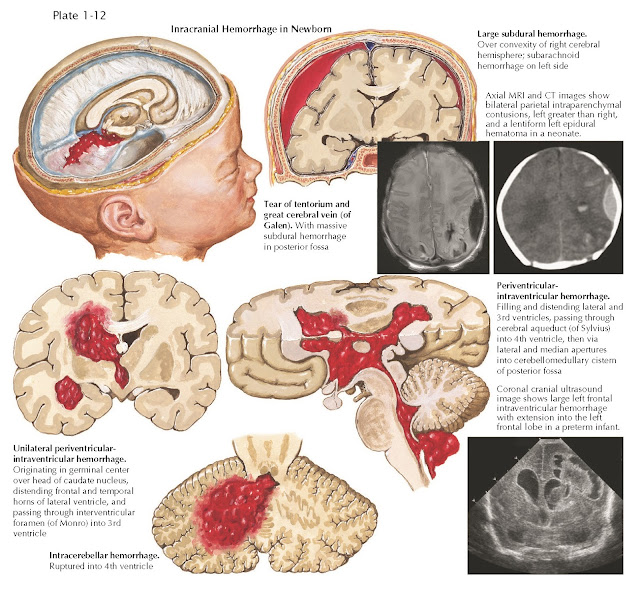

Intracranial hemorrhage in the neonate is classified by location and in order of frequency as (1) periventricularintraventricular, (2) subarachnoid, (3) subdural, or (4) posterior fossa hemorrhage. All neonates should be followed closely for symptomatic anemia.

Periventricular-intraventricular

hemorrhage (IVH) originates in

the germinal matrix near the lateral ventricles and typically is observed in

infants born preterm before 34 weeks’ gestation (Plate 1-12). In preterm infants, the inherent friability of the germinal

matrix is often complicated by cardiopulmonary compromise during birth and

physiologic stresses of adjusting to the extrauterine environment in the early

neonatal period. Massive bleeding, now quite rare, precipitates a bulging

fontanelle, respiratory difficulties, tonic posturing, seizures, anemia and, ultimately, multisystem

failure. Minor bleeding detected with serial cranial ultrasonography is now

more common. Some preterm infants will develop ventriculomegaly without cranial

growth or elevated intracranial pressure, consistent with hydrocephalus ex

vacuo from encephalomalacia. Approximately 15% of preterm infants with IVH will

require surgical intervention for symptomatic hydrocephalus. Long-term

neurologic deficits are common in preterm infants with IVH, including cerebral

palsy, epilepsy, cognitive delay, and behavioral abnormalities. In full- term

infants, IVH typically occurs secondary to deep central venous thrombosis, and

approximately half of these infants will develop early or late hydrocephalus.

Term infants with IVH are also prone to chronic neurologic deficits, including

epilepsy, cognitive delay, and behavioral abnormalities.

Subarachnoid hemorrhage may be caused by asphyxia or by forces of normal

delivery. In full-term infants, it may be

asymptomatic or associated with focal or generalized seizures, with no focal

deficits. Subdural hemorrhage results from tears in the falx cerebri and

tentorium, rupture of bridging veins over the hemispheres, or occipital

osteodiastasis in breech delivery. Causes include excessive molding forces

during delivery, the infant’s size, and difficult extractions. Symptoms are

acute or subacute hemiparesis, focal seizures, and ipsilateral pupillary

abnormalities. Surgical drainage is the appropriate treatment in select cases.

Cranial ultrasonography rarely provides adequate information, and either a

rapid computed tomography (CT) or MRI scan is needed for management decisions.

Posterior fossa hemorrhage can result from tentorial trauma or occipital

osteodiastasis. Either a rapid CT or MRI scan is needed for management

decisions; cranial ultrasonography does not provide adequate imaging to assess

the mass effect of the hematoma. Surgical drainage is rarely indicated.