CLINICAL PROBLEMS AND CORRELATIONS

OF THE THORACOLUMBAR

SPINE

Low back pain, with or without leg pain, is very common in the population, particularly in middle-aged and older adults. Degeneration of the intervertebral disc and some degree of low back pain and stiffness are nearly universal features of aging. Degenerated discs have decreased height, increased posterior and lateral bulging, and reduced ability to dissipate compression forces. As a result, associated changes occur, including abnormal loading of the facet joints with development of facet arthritis, osteophyte formation, greater stress on adjacent ligaments and muscles, and thickening of the ligamentum flavum. In some patients, these changes may result in back pain, although it is difficult to isolate the primary source of low back pain in most instances. In some cases, back pain may become chronic. Chronic low back pain, defined as persistent symptoms for longer than 6 to 8 weeks, is common among people older than 40 to 50 years of age and those working in occupations requiring frequent bending, lifting, or exposure to repetitive vibration (e.g., truck drivers). Obesity, smoking, and poor physical fitness are all risk factors for disc degeneration.

A typical feature of back pain is its frequent radiation to one or both

buttocks. The pain can additionally radiate to the posterior thigh. It is

frequently exacerbated by lifting and bending activities and relieved with rest.

As with all chronic pain conditions, depression may aggravate symptoms and make

treatment more challenging.

|

| DEGENERATIVE DISC DISEASE |

Examination typically shows mild tenderness in the lower back or

sacroiliac region. Flexion and extension of the spine may be limited and

painful. The straight-leg raising sign is typically absent, and findings of the

neurologic examination are normal. Patients with associated

psychological issues may display nonorganic findings, such as exaggerated pain

behaviors and non-anatomic localization of symptoms.

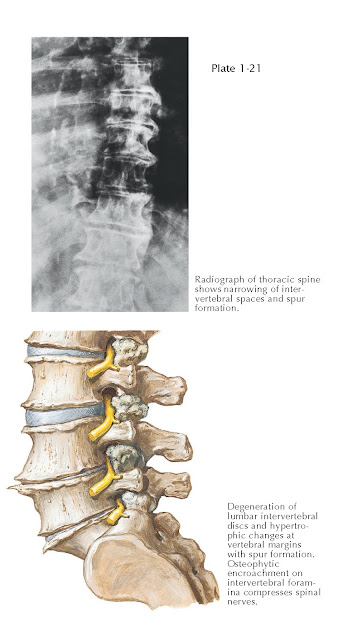

Radiographs and MR images of the spine reveal changes that are difficult

to differentiate from normal age-related changes. These include decreased disc

height, anterior vertebral body osteophytes, and decreased disc hydration (see Plate 1-21). Screening

radiographs to rule out tumor, infection, or an inflammatory arthritic process

are appropriate for patients with pain lasting

longer than 6 weeks. MRI should be reserved for patients with unusual symptoms

in whom an occult and sinister process is suggested, such as infection, tumor,

or fracture. It is also utilized as a diagnostic tool for patients with

unremitting symptoms in whom symptomatic nerve compression is suggested and who

are surgical candidates.

Recurrent episodes of back pain are typical, and most can be managed

nonoperatively with nonsteroidal anti- inflammatory drugs (NSAIDs), general

conditioning exercises,

active physical therapy, weight reduction, and smoking cessation. Unremitting

pain necessitates further evaluation. Operative treatment is rarely indicated

for back pain, and the role of fusion or arthroplasty for patients with

discogenic low back pain is controversial.

LUMBAR DISC HERNIATION

The nucleus pulposus may herniate posteriorly or posterolaterally and

compress a nerve root, resulting in lumbar radiculopathy (leg pain in a

dermatomal distribution). The herniation may be protruded (with the

anulus intact), extruded (through the anulus but contained by the

posterior longitudinal ligament), or sequestered (free within the spinal

canal). Pain results from nerve root compression and from an inflammatory

response initiated by various cytokines released from the nucleus pulposus (see

Plate 1-22).

Patients with lumbar disc herniation typically are young and middle-aged

adults with a history of previous low back pain. The pain may be exacerbated by

a bending, twisting, or lifting event but may also develop insidiously and

abruptly. The central portion of the posterior longitudinal ligament is the

strongest portion of the ligament and resists direct posterior extrusions. More

than 90% of lumbar disc herniations occur posterolaterally at L4-5 and L5-S1.

Posterolateral disc herniations may cause neural compression and radicular pain

involving the traversing spinal nerve. For example, an L4-5 posterolateral disc

herniation will typically affect the L5 nerve root. Occasionally, a disc

herniation will be located far lateral and can affect the more proximal exiting

nerve root within the foramen and can cause radicular pain

corresponding to the vertebral level cephalad to the disc (e.g., an L4-5 far

lateral disc herniation will affect the proximally exiting L4 nerve root).

Increasing pressure or stretch on the compressed nerve root exacerbates

pain. Pain can also increase with any activity that increases intra-abdominal

pressure, such as sitting, sneezing, and lifting. It is typically decreased by

lying down with a pillow under the legs or by lying on

the side with the hips and knees flexed (fetal position). Symptoms can be

variable, but pain and sensory disturbances typically follow the dermatome of

the nerve root(s) affected.

On examination, the patient may lean toward the affected side to relieve

compression on the affected root. The straight-leg raise test (lifting the leg

with the knee straight) is a classic sciatic nerve tension sign that indicates L5 or S1

root inflammation and should be performed on both legs. A positive test

typically reproduces the patient’s radicular symptoms below the knee. The

specificity of the test is heightened when raising the contralateral leg

provokes symptoms on the affected side (the cross-leg sign). The comparable

test for a more proximal lesion affecting the L4 root or higher is the femoral

nerve stretch test, which is performed by having the patient lie on the

nonaffected side and by having the examiner extend the affected hip with the

knee flexed. A positive test reproduces the patient’s proximal leg pain.

Radiographs of the lumbar spine may be normal but are useful in ruling

out other conditions such as fracture. MRI is the study of choice to delineate

the location and type of disc herniation. Most patients respond to symptomatic

treatment such as NSAIDs, muscle relaxants, oral narcotics, a short course of

oral corticosteroids, or epidural corticosteroid injection and will note

improvement of symptoms by 6 weeks.

Indications for surgery include cauda equina syndrome, urinary retention

or incontinence, progressive neurologic deficit, severe single nerve root

paralysis, and radicular pain lasting longer than 6 to 12 weeks. The goal of

surgery is to relieve pressure on the affected nerve root or cauda equina. The

procedure usually involves a small laminotomy and excision of the herniated

disc fragment (see Plate 1-22). Lumbar discectomy typically provides dramatic

relief of symptoms in 85% to 90% of patients. Recurrent disc herniations may

occur in 5% to 10% of patients. Possible complications of surgery include

injury to the neural elements, postoperative infection, durotomy, and

persistent pain.

CAUDA EQUINA SYNDROME

Multiple nerve roots of the cauda equina may be severely compressed by a

large central disc herniation or other pathologic process such as epidural

abscess, epidural hematoma, or fracture, resulting in a rapid onset of

neurologic deficit. Midline sacral nerve roots that control bowel and bladder

function are particularly vulnerable to such compression. Typical symptoms

include bilateral lower extremity radicular pain and motor/sensory dysfunction,

saddle anesthesia in the perineum, difficulty voiding, or frank bowel or

bladder incontinence. Patients with cauda equina syndrome require emergent

surgical decompression. Even with prompt treatment, however, the return of

neurologic function may be incomplete.

LUMBAR SPINAL STENOSIS (CONTINUED)

Lumbar spinal stenosis may result from any condition that causes

narrowing of the spinal canal or neural foramina with subsequent compression of

the nerve roots at one or more levels. The most common cause is degenerative

changes in the disc and facet joints. These degenerative changes are often

associated with a spondylolisthesis, which is an anterior slipping

(anterolisthesis) of one vertebra on the subjacent level. Patients with

achondroplasia or other conditions that alter growth of the posterior vertebral

arch may also develop stenosis with progressive symptoms in the second or third

decade of life. Lumbar stenosis may also be congenital or may be caused by

traumatic or post-operative changes.

Narrowing of the spinal canal is common in persons older than 60 years

of age, but most persons have minimal symptoms. The spine is a three-joint

complex comprising the intervertebral disc anteriorly and the two facet joints

posteriorly. It is thought that the pathology of spinal stenosis begins

anteriorly in the disc and involves the facet joints secondarily. Skeletal

changes associated with stenosis in the older population include disc bulging

and narrowing, degeneration and osteophyte formation of the facet joints, and, occasionally,

spondylolisthesis. Soft tissue changes associated with stenosis include

buckling or thickening of the ligamentum flavum and posterior longitudinal

ligament, as well as bulging or frank herniation of the disc.

Symptomatic lumbar spinal stenosis afflicts both sexes and typically

does not develop until after 40 years of age, unless there is a congenital

component. Typical symptoms include a diffuse pain in the buttocks and

posterior thighs or pain in a dermatomal and radicular pattern. Back

pain may or may not be present. Symptoms are frequently bilateral, but one

extremity may be more severely affected than the other. Patients note pain and

often numbness or weakness when walking, usually beginning in the buttocks or

thighs, and often progressing to the calves and feet. This condition is also

termed neurogenic claudication. Symptoms are typically relieved by

sitting, bending forward, or leaning on an object.

Forward-flexion of the lumbar spine reduces discomfort and improves exercise

tolerance by expanding the spinal canal, thereby relieving neural compression.

As a result, patients with symptomatic spinal stenosis sometimes walk with

their hips and knees flexed to allow for lumbar flexion (see Plate 1-23).

Patients typically report improved symptoms when leaning on a shopping cart,

walking up hills, or exercising on a recumbent bike, all of which permit a

slight degree of lumbar flexion, thereby relieving neural compression.

Vascular claudication may mimic neurogenic claudication and should be

ruled out because they may coexist. As with neurogenic claudication, patients

with vascular claudication may have increased leg pain with exercise that is

relieved by rest. However, patients with vascular claudication do not have pain

relief with lumbar flexion or walking uphill, have a fixed as opposed to

variable claudication distance, rarely have back pain, often have loss of calf

hair, and typically have diminished or absent peripheral pulses (see Plate

1-23).

Findings on examination are often limited in patients with spinal

stenosis. Lumbar range of motion may be either normal or diminished. Muscle

weakness, if present, is often subtle and may only be observed after having the

patient walk. Weight-bearing radiographs should be obtained and usually demonstrate

typical age-related changes of facet joint arthrosis, diminished disc height,

or a degenerative spondylolisthesis, most common at L4-5 and L3-4. The

differential diagnosis includes vascular claudication, peripheral neuropathy

associated with diabetes mellitus or vitamin B12 or folic acid deficiency,

abdominal aortic aneurysm, infection, and tumor.

|

| DEGENERATIVE LUMBAR SPONDYLOLISTHESIS |

Nonoperative management is initially symptomatic and includes physical

therapy, NSAIDs, activity restriction, epidural corticosteroid injections,

weight reduction, and smoking cessation. Membrane-stabilizing agents such as

gabapentin have also been useful in reducing symptoms. When symptoms persist

and surgery is an option, diagnostic imaging with either MRI or CT

myelography should be performed. Weight-bearing lumbar radiographs are

mandatory, and flexion and extension lumbar spine views may also be useful to

rule out an associated degenerative spondylolisthesis. If spondylolisthesis is

present, decompression is usually accompanied by spinal fusion of the affected

levels. If no degenerative spondylolisthesis is present,

surgical therapy usually involves neural decompression alone.

Surgery is most effective to relieve leg symptoms of neurogenic

claudication. It is less successful in patients in whom back pain is the

predominant symptom and in patients with significant comorbidities such as

smoking, obesity, or diabetes. Surgical decompression of the stenotic level(s)

is usually palliative (see Plate 1-25). This is most

commonly achieved by a laminectomy, with foraminotomy as needed. Iatrogenic

instability can occur after complete removal of a unilateral facet joint, by

more than 50% facet resection bilaterally, or by removal of more than one third

of the pars interarticularis bilaterally. In such cases, a concomitant spinal

fusion should be considered. Recurrence of stenosis after decompression may

occur, particularly at adjacent levels to a concomitant spinal fusion.

DEGENERATIVE SPONDYLOLISTHESIS: CASCADING SPINE

DEGENERATIVE LUMBAR SPONDYLOLISTHESIS

Spondylolisthesis is translation (slippage) of one vertebra in relation

to an adjacent segment. The superior vertebra typically slips in an anterior

(forward) direction in relation to the inferior vertebra (anterolisthesis) (see

Plate 1-26). Retrolisthesis,

in which the superior vertebra slips posteriorly, can also occur. This is

occasionally observed in degenerative spondylolisthesis involving the upper

lumbar levels. The causes of spondylolisthesis vary, but the vast majority of

patients have either an isthmic or degenerative spondylolisthesis (see Plate

1-25). Isthmic spondylolisthesis typically occurs at L5-S1, begins during

adolescence, and is discussed elsewhere.

In degenerative spondylolisthesis (spondylolisthesis with an intact

neural arch), erosion and narrowing of the disc and facet joints lead to

segmental instability. Because the posterior arch is intact, the slippage

causes stenosis, which can be aggravated with flexion. This condition typically

occurs in adults past age 40, is more common in

women and blacks, and is most common at the L4-5 level. It can also occur at

other levels, however, and can result in the appearance of a “cascading spine”

(see Plate 1-26).

Symptoms include back pain, radicular pain, and neurogenic claudication.

Indications for surgical management include persistent claudicatory leg pain,

neurologic weakness, and, rarely, cauda equina syndrome. Because the affected

segments are unstable, decompression is usually

combined with fusion (arthrodesis). The addition of instrumentation improves

fusion rate. Decom- pression alone is associated with poorer outcomes than

decompression with concomitant fusion and may be associated with progression of

spondylolisthesis. It is therefore typically reserved for elderly, low-demand

patients with significant collapse of the disc and no motion detected on

flexion-extension lumbar radiographs.