BENIGN PROSTATIC HYPERPLASIA II: SITES OF HYPERPLASIA

AND ETIOLOGY

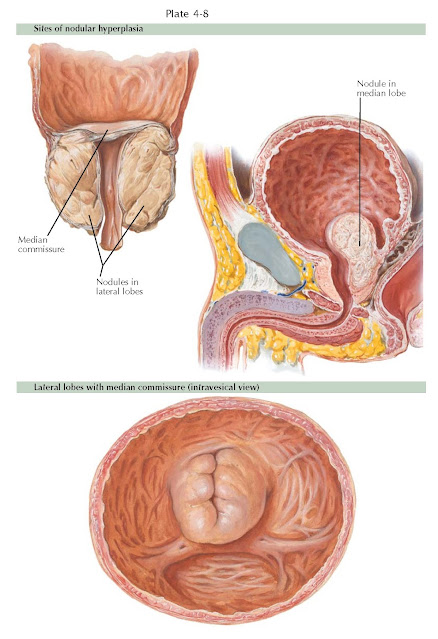

Prostatic enlargement due to benign prostatic hyperplasia (BPH) presents with several typical growth configurations. The nodules usually enlarge in a symmetrical manner, although in some instances one side may predominate. On rectal examination, this may present as prostatic asymmetry and, without induration or nodularity, is not suspicious for carcinoma. As nodules grow, they have been termed median, lateral, and anterior lobe hyperplasia, according to their location cystoscopically. These designations are misnomers because the prostate is generally not a lobulated organ. These terms simply designate general cystoscopic locations.

The most frequent types of prostatic enlargement are “bilobular” (the two

lateral lobes) and “trilobular” (the two lateral plus the median lobe)

hyperplasia. Isolated median lobe enlargement may occur without lateral lobe

enlargement, but it is much less common. Rarely, nodules can originate in the

roof of the urethra within the anterior zone and project downward into the

bladder, giving the appearance of a rounded “anterior” lobe.

With lateral lobe hyperplasia, the nodules grow to surround the prostatic

urethra; as a result, it becomes considerably elongated. Growth is confined

within the prostate without projection into the bladder neck. The lateral lobes

may grow to great size, with only a minimal degree of urinary obstruction. When

they extend into the bladder neck, this projection may interfere with the

opening of the bladder neck and result in urinary obstruction. Median lobe

enlargement begins in the posterior urethra and, following the line of least

resistance, projects as a mass up through the bladder neck and into the

bladder. Other nodular enlargement occurs in the vicinity of the Albarrán

glands (see Plate 4-2) just beneath the bladder neck and tends to produce

intravesical hypertrophy.

The degree of BPH cannot be accurately judged from the rectal

examination, which only reveals the size of lateral lobe enlargement below the

bladder neck. As such, the rectal examination does not accurately correlate

with the degree of obstruction or with voiding symptoms.

The origin of BPH remains unclear. Because hyperplasia arises mainly

within the transition zone that contains an unusual juxtaposition of glandular

and stromal elements, one theory purports that BPH develops as a consequence of

stromal cell dysregulation and is induced by the effects of androgens and

estrogens. This change in the prostatic stromal–epithelial cell interactome

that occurs with age may lead to an inductive effect on prostatic growth and is

termed the embryonic reawakening theory. Another theory, termed the DHT

hypothesis, suggests that a shift in prostatic androgen metabolism occurs with aging that leads to an abnormal accumulation of dihydrotestosterone

(DHT) and stimulating prostatic enlargement. The stem cell theory of BPH

advocates an increase in the total prostatic stem cell number and/or an

increase in the clonal expansion of stem cells into amplifying and transit

cells with age. What is clear is that aging and the presence of a functional

testis are the two established risk factors for the development of BPH. There

are ethnic trends in occurrence, as the condition

is more common in Caucasian and black men than it is in Asian men. Vascular

disease, infection, and sexual activity do not correlate with BPH, but it is

less likely to occur in hypogonadal men. The active androgen responsible for

prostatic growth and development is DHT, and the administration of 5-alpha

reductase inhibitors, commonly prescribed for urinary symptoms due to BPH, will

reduce prostatic volume by one-third over 6 months.