ANATOMY OF THE THORACOLUMBAR

AND SACRAL SPINE

THORACIC

VERTEBRAE AND LIGAMENTS

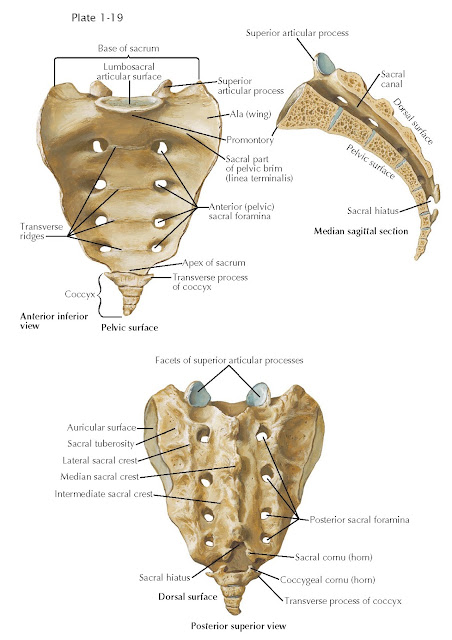

The 12 thoracic vertebrae (T1 to T12) are intermediate in size between the smaller cervical and the larger lumbar vertebrae. The heart-shaped vertebral bodies are slightly taller posteriorly than anteriorly, producing a slight wedge shape (see Plate 1-17). Vertebrae are easily recognized by their costal facets on both sides of the bodies and on all the transverse processes except those of T11 and T12. The costal facets articulate with the facets on the heads and tubercles of the corresponding ribs. The spinal canal is smaller and more rounded than in the cervical spine and corresponds to the more circular shape of the spinal cord in the thoracic region. The spinal canal is formed by the posterior surfaces of the vertebral bodies and by the pedicles and laminae forming the vertebral arches. The stout pedicles are directed posteriorly; they have shallow superior and much deeper inferior vertebral notches. The laminae are short and relatively thick and partially overlap each other from above downward.

The typical thoracic superior articular processes project upward from

the junction of the pedicles and the laminae, and their facets slant

posteriorly and slightly upward and outward. The inferior articular processes

project downward from the anterior parts of the laminae, and their facets face

forward and slightly downward and inward.

|

THORACIC VERTEBRAE AND LIGAMENTS

Most of the thoracic spinous processes are long and inclined inferiorly and posteriorly. Those of the upper and lower thoracic vertebrae are more horizontal. The transverse processes are also relatively long and extend posterolaterally to form the junctions of the pedicles and laminae. Except for the lowest two (or occasionally three) thoracic vertebrae, the transverse processes have small oval facets near their tips that articulate with similar facets on their corresponding rib tubercles.

Adjacent vertebral bodies are connected by the intervertebral discs as

well as by the anterior and posterior longitudinal ligaments; the transverse

processes are connected by the intertransverse ligaments; the laminae are

connected by the ligamentum flavum; and the spinous processes are connected by

the supraspinous and interspinous ligaments. The facet joints, which form from

adjacent superior and inferior articular processes, are synovial joints and are

covered by a fibrous articular capsule.

Costovertebral Joints

The ribs are connected to the vertebral bodies and the transverse

processes by various ligaments. The costocentral joints, between the bodies and

the rib heads, have articular capsules. The second to tenth costal heads, each

of which articulates with two vertebrae, are also connected

to the corresponding vertebral discs by interarticular ligaments. Radiate

(stellate) ligaments unite the anterior aspects of the rib heads with the sides

of the vertebral bodies above and below the discs. The rib head articulates

with both the upper border of its own vertebra as well as the lower border of

the vertebra above (i.e., the ninth rib articulates with the vertebral bodies

of both T8 and T9). The costotransverse joints between the facets on the

transverse processes and on the tubercles of the ribs are also surrounded by

articular capsules. They are reinforced by a (middle) costotransverse ligament

between the rib neck and transverse process of the vertebra above and a lateral

costotransverse ligament interconnecting the end of a transverse process with

the nonarticular part of the related costal tubercle.

LUMBAR VERTEBRAE AND INTERVERTEBRAL DISCS

LUMBAR VERTEBRAE AND INTERVERTEBRAL DISCS

The five lumbar vertebrae (L1 to L5) are the largest separate vertebrae

and are distinguished by the absence of costal facets (see Plate 1-18). The

vertebral bodies are wider from side to side than from front to back, with

upper and lower surfaces that are kidney shaped and almost parallel, except in

the case of the fifth vertebral body, which is slightly wedge shaped. The

vertebral foramina have a “teardrop” shape. The pedicles are short and strong,

arising from the upper and posterolateral aspects of the bodies. The laminae

are short, broad plates that meet in the middle to form nearly horizontal

spinous processes that are perpendicular to the lamina.

The intervals between adjacent laminae and spinous processes (interlaminar

spaces) are wider than in the cervical and thoracic spine.

The articular processes (which form the facet joints) project superiorly

and inferiorly from the area between the pedicles and laminae. The facet joints

are oriented relatively vertically, which allows for some flexion and extension

but little rotation. The transverse processes of L1 to L3 are long and slender,

whereas those of L4 and L5 are more pyramidal. Near the base of each

transverse process are small accessory processes; other small, rounded

mammillary processes protrude from the posterior margins of the superior

articular processes.

The fifth lumbar vertebra is atypical. It is the largest, with its body

deeper anteriorly; its inferior articular facets face almost forward and are

set more widely apart, and the roots of its stumpy transverse processes are

continuous with the entire lateral surfaces of the pedicles.

Interposed between the adjacent vertebral bodies are intervertebral

discs. These are immensely strong fibrocartilaginous structures that provide

powerful bonds between vertebrae and act to buffer axial loads. The discs

consist of outer concentric layers of fibrous tissue, the anulus fibrosus. The

fibers in adjacent layers of the anulus are arranged obliquely but in opposite

directions to resist torsion. The anulus fibrosus contains a central, springy

and pulpy zone called the nucleus pulposus. The vascular and nerve supply to

the discs is minimal. If the fibers of the annulus fail as a result of injury

or disease, the enclosed nucleus pulposus may extrude posteriorly through the

rent in the annulus and press on adjacent neural structures.

In the normal spine, the discs account for almost 25% of the height of the

vertebral column; they are thinnest in the upper thoracic region and thickest

in the lumbar region. In the vertical section, the lumbar discs are moderately

wedge shaped, with the thicker edge anteriorly. The convexity (lordosis) of the

normal lumbar spine is due more to the shape of the discs than to the shape of

the vertebral bodies. With aging, the nucleus pulposus undergoes changes: its

water content decreases, its mucoid matrix is gradually replaced by

fibrocartilage, and it ultimately comes to resemble the anulus fibrosus.

Although the resultant loss of height in each disc is small, it may amount to

an overall decrease of 2 to 3 cm in the length of the vertebral column.

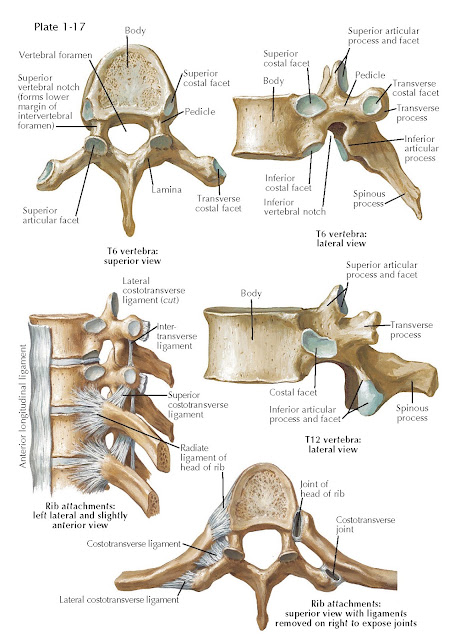

SACRAL SPINE AND PELVIS

The principal function of the pelvis is to transmit body weight to the

limbs and absorb the muscular stresses of an upright posture (see Plate 1-19). The center

of gravity of the body passes just anterior to the sacral promontory.

The sacrum, composed of five fused vertebrae, broadens laterally into

the sacral ala. The sacral nerve roots emerge through the anterior and

posterior sacral foramina just medial to the sacral ala. The anterior surface

of the sacrum is smooth. Dorsally, the surface is highly irregular to

facilitate ligamentous attachments. The lateral articular surfaces of the

sacrum articulate with the pelvis, forming the sacroiliac joint. The joint

surfaces contain complementary elevations and depressions to diminish motion.

Additionally, the anterior and posterior sacroiliac

joint capsules have overlying sacroiliac ligaments, which are among the

strongest in the body.

LUMBOSACRAL LIGAMENTS

The anterior longitudinal ligament is a straplike band that increases in

width, moving caudally down the spine. It extends from the anterior tubercle of

the atlas to the sacrum. It is firmly attached to the anterior margins of the

vertebral bodies and discs (see Plate 1-20). The posterior longitudinal ligament is broader in

the upper spine and becomes narrower as it traverses caudally. It lies within

the vertebral canal immediately behind the vertebral bodies. Its upper end is

continuous with the tectorial membrane, and it extends from the axis to the

sacrum. The edges of the ligament are serrated, particularly in the lower

thoracic and lumbar regions, because it spreads out between its attachments to

the vertebral bodies to blend with the annular fibers of the discs. The ligament

is separated from the posterior vertebral body surfaces by basivertebral veins

that join the anterior internal venous plexus. The posterior longitudinal

ligament is stronger in the midline and weaker laterally, which helps to

explain the propensity for lumbar disc herniations to occur in a

posterolateral, rather than midline, location.

|

| LUMBOSACRAL LIGAMENTS |

The ligamentum flavum is largely composed of yellow elastic tissue and

joins adjacent laminae. It extends from the anteroinferior surface of the

lamina above to the posterosuperior aspect of the lamina below, and from the

midline to the facet joint capsules laterally. There is a midline raphe

separating the right and left ligaments. The ligaments increase in thickness

from the cervical to the lumbar spine.

The supraspinous ligaments connect the tips of the spinous processes

from the seventh cervical vertebra to the sacrum. They are continuous with the

nuchal ligament in the cervical spine and the interspinous

ligaments immediately anterior, and they increase in thickness caudally. The

interspinous ligaments are thin, membranous structures between the roots and

apices of the spinous processes and are best developed in the lumbar region.

The interosseous sacroiliac ligaments are formed by short, thick bundles

of fibers connecting the sacral and iliac tuberosities. The dorsal sacroiliac

ligaments fill the deep depression between the sacrum and the iliac bones

dorsally. The sacrotuberous ligament is long, flat, and triangular. It arises

from the posterior superior and posterior inferior iliac spines and from the

back and side of the sacrum. The fibers converge on the ischial tuberosity. The

sacrospinous ligament arises from the lateral aspect of the lower sacrum and

coccyx and attaches to the ischial spine. This ligament converts the greater

sciatic notch into the greater sciatic foramen and with the

sacrotuberous ligament forms the lesser sciatic foramen. The lumbosacral joint

unites L5 and the sacrum. These vertebra are united by

the same ligamentous structures found throughout the lumbar spine with the

addition of the strong iliolumbar ligament traversing laterally from the

transverse process of L5 to the posterior part of the iliac crest. The

iliolumbar ligament resists the tendency of the lumbar vertebra to slip down the slope of

the sacral promontory.