TUBERCULOSIS

Tuberculosis

remains a major infectious disease both worldwide and in the United States. The

pathogen responsible for most cases, Mycobacterium tuberculosis, infects

one third of the world’s population, and it is responsible for over 2 million

deaths per year. The incidence of this disease is declining in the United

States at a rate of approximately 3% to 6% per year; however, tuberculosis

remains an important cause of mortality and morbidity among those in immunocom promised states, especially those coinfected with the

human immunodeficiency virus (HIV).

Although a majority of those infected with Mycobacterium

tuberculosis develop disease restricted to the lungs, a recent survey of

cases in the United States found that 19% had only extrapulmonary disease, whereas

6% had combined pulmonary and extrapulmonary disease. Of those with

extrapulmonary disease, 6.5% had urogenital involvement. In addition, the

relative proportion of extrapulmonary cases appears to be increasing: despite a

steady decline in the number of new pulmonary tuberculosis cases, there has

been little change in the number of new extrapulmonary cases. Worldwide,

urogenital involvement is even more common, occurring in up to 40% of

extrapulmonary cases. There is evidence, however, that even this number may be

an underestimate; in one autopsy study, 73% of patients with pulmonary

tuberculosis were found also to have a renal focus.

Urogenital tuberculosis affects men twice as often as

women, and the average age at presentation is approximately 40 years old. HIV

infection is also a major risk factor not only for active tuberculosis in

general, but also for extrapulmonary spread and reactivation.

PATHOPHYSIOLOGY

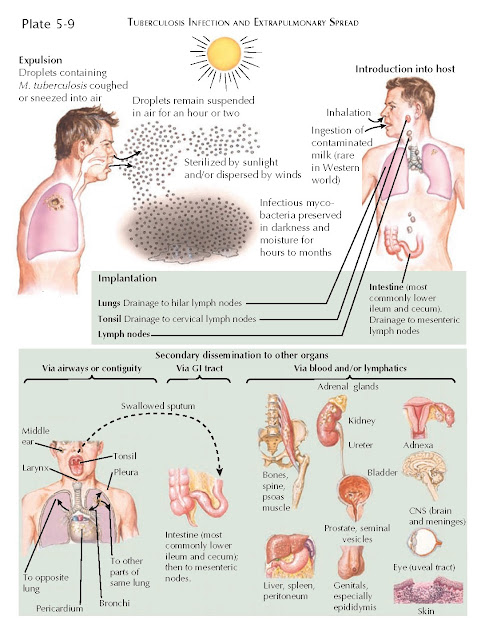

Upon inhalation of airborne bacilli, patients may experience

a primary, usually silent, infection that involves formation of granulomas in

the pulmonary alveoli. During this initial phase, lymphatic and then

hematogenous seeding of distant organs such as the kidneys and reproductive organs can occur. In rare instances, wide and uncontrolled

dissemination of mycobacteria may lead to miliary tuberculosis, which can also

involve the kidneys (see separate section later).

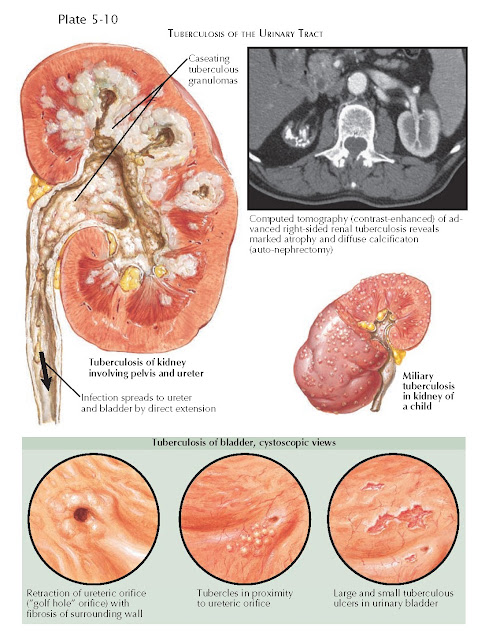

In the urinary system, the renal cortex is the usual

site of primary infection. After initial seeding, the disease course is

indolent. Indeed, bacilli can remain latent within granulomas for decades or

more, both in the kidneys and elsewhere. Reactivation can occur because of a

decline in immunity because of age, disease, or malnutrition. Reactivation of

renal tuberculosis may lead to further granuloma formation, parenchymal

cavitation, papillary necrosis, calcification, and, in rare cases, tuberculous

interstitial nephritis.

As the renal disease becomes advanced, it may spread

to the rest of the urinary system by direct extension. In the ureter,

strictures and calcification may occur. In the bladder, ulceration and fibrosis

may occur, leading to wall contraction and a decrease in storage capacity. Fibrosis

adjacent to the ureteric orifice may cause it to become retracted and assume a

“golf hole” appearance.

Genital disease may occur either because of

hematogenous spread or contiguous extension from the urinary system.

PRESENTATION AND DIAGNOSIS

The symptoms of genitourinary tuberculosis can be very

nonspecific. Patients often complain of urinary frequency and may, in some

cases, experience gross hematuria or flank pain. Some patients may also have

constitutional symptoms, including fever and weight loss.

About 90% of patients will have abnormal urinalysis,

which may reveal positive leukocyte esterase, hematuria, proteinuria, and low

urine pH. About 1 in 10 patients will have only frank hematuria, whereas up to

half have microscopic hematuria. As Mycobacterium tuberculosis does not

convert urinary nitrates, dipstick is often negative for nitrites.

The classic urinary finding found in up to one quarter of patients is sterile pyuria, where urine contains numerous white

blood cells but no bacterial growth is seen on standard cultures. Of note,

bacterial growth does not necessarily rule out renal tuberculosis, since

secondary bacterial infection is common.

If sterile pyuria is seen, the differential diagnosis

also includes chlamydial urethritis, pelvic inflammatory disease,

nephrolithiasis, or renal papillary necrosis. If constitutional symptoms and

hematuria are present, a malignancy of the urinary or genital system should

also be suspected.

A physician may suspect urogenital tuberculosis if the

patient has risk factors for tuberculosis exposure, a history of a positive

purified protein derivative (PPD) test, a history of immunocompromise, and

constitutional symptoms. It is not uncommon, however, for physicians to

prescribe antibacterial treatment at first presentation. A lack of positive

urine cultures, no response to antimicrobials, or recurrent episodes of

cystitis in the setting of suggestive risk factors should raise a suspicion of

mycobacterial infection and prompt further evaluation. A radiograph may reveal areas

of focal calcification in the kidneys and the lower genitourinary tract.

Ultrasonography may reveal calcification, hypoechoic renal abscesses, and

shrunken kidneys. CT may demonstrate calcifications, renal scarring and

cavitation, papillary necrosis, strictures of the collecting system, and

diminution of renal function. Imaging of the thorax should also be performed to

rule out concomitant pulmonary or spinal infection. Many patients will have

evidence of prior pulmonary infection, and up to 30% to 40% will be found to

have active pulmonary disease.

Once tuberculosis is suspected, the bacillus can be

identified in urine by acid-fast staining. Because sensitivity is low, multiple

early morning midstream voided specimens are often collected to increase

detection power. Culture on either liquid broth or solid Löwenstein-Jensen

medium remains the gold standard for diagnosis, and it also has the advantage

of providing information about mycobacterial drug susceptibilities.

Although culture sensitivity can be as high as 80%,

results can take as long as 6 to 8 weeks. For that reason, polymerase chain

reaction (PCR) studies may be performed to detect M. tuberculosis in

urine earlier in the clinical course. The advantage of this test is not only

its high sensitivity (up to 95%), but also its fast turnaround time, with

results often obtained within 24 hours.

In situations when there is a high clinical suspicion

for tuberculous disease, but microbiologic testing is not definitive, more

invasive methods of diagnosis, such as percutaneous tissue biopsy, may be

required. Histopathologic examination of the obtained tissue reveals caseating

granulomas.

In immunocompetent patients, an intradermal tuberculin

test (PPD) can be performed as an additional screen for tuberculosis exposure;

however, it is not helpful in diagnosis of the disease because results have

been reported as positive in only 60% of patients with urinary tuberculosis.

Interpretation of tuberculin test results should follow standard cut-off

values: 5 mm or more for immunocompromised patients, 10 mm or more for patients

at high risk (inmates, health-care workers, long-term care facility residents,

intravenous drug users, and immigrants), and 15 mm or more for patients without

any risk factors. A positive tuberculin test result indicates prior exposure

but is not diagnostic of active disease. In patients with advanced HIV or other

immunocompromising conditions, tuberculin test results may be negative

secondary to anergy and should not be used to rule out tuberculosis.

TREATMENT

The treatment of urogenital tuberculosis involves a

combination of antituberculous therapy and surgical resection, where possible,

of local disease. Consultation with experts should be sought, given not only

the complexity of the disease course but also the potential adverse effects

associated with treatment.

Pending the return of culture and sensitivities, the

patient should be initiated on a four-drug regimen that includes isoniazid,

ethambutol, rifampin, and pyrazinamide. If cultures indicate the organism is

sensitive to isoniazid, rifampin, and pyrazinamide, the ethambutol can be

stopped. After 8 weeks, pyrazinamide is usually stopped, because it has an

early bactericidal effect.

The duration of therapy with the remaining two agents depends on the patient’s immune status. Therapy may also need to be adjusted if infection occurs in an

area with high levels of multidrug-resistant or extensively drug-resistant

tuberculosis.

PROGNOSIS

In the developed world, tuberculosis is rarely a cause

of chronic kidney disease. Preservation of renal function, however, depends on

early detection to limit renal parenchymal destruction. In developing

countries, where diagnosis and treatment are more likely to be delayed,

permanent loss of renal function is more common.

MILIARY TUBERCULOSIS

In addition to being the site of locally reactivating

granulomas, as described previously, the kidneys may rarely be involved in the

disseminated disease known as miliary tuberculosis.

Miliary tuberculosis results from widespread

hematogenous dissemination of tuberculous bacilli after invasion of the

pulmonary circulation. It may occur during the time of primary infection or at

reactivation, and it is often associated with the extremes of age and other

conditions that compromise the immune system. Patients have more pronounced

constitutional systems and extensive pulmonary disease. Overwhelming systemic

illness may overshadow the effects of renal involvement. The workup of miliary

tuberculosis includes acid-fast bacillus smears, culture, PCR, and histopathologic

examination of affected tissues (e.g., bone marrow, lymph nodes, liver). If the

kidney is affected, numerous granulomatous lesions may be present throughout

the cortex and, less commonly, the medulla. On microscopic examination these

granulomas reveal central caseous necrosis.

Rapid diagnosis of military tuberculosis is essential,

and treatment with the combination regimen described above should be promptly initiated.