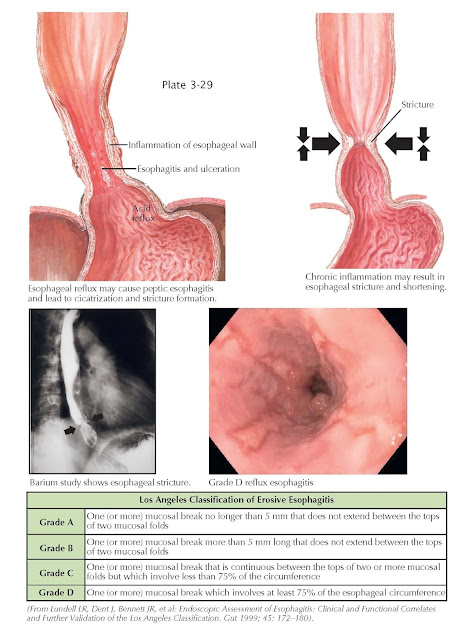

Reflux Esophagitis

Gastroesophageal reflux is defined simply as the passage of gastric contents into the esophagus. Gastroesophageal reflux disease (GERD) occurs when the content volume is abnormal and is associated with symptoms and/or gross esophageal injury. Within this definition are a multitude of mechanisms and symptoms, some of which are bothersome and some of which can lead to injury and even death. As a result, GERD may be arbitrarily divided into mild and severe forms. In the mild form, symptoms result from reflux but the caustic nature of the refluxant is not of sufficient strength, duration of esophageal exposure, and/or quantity to cause gross esophageal injury.

This type of reflux is likely explained by mild

dysfunction of the normal mechanisms that prevent reflux from occurring. For

example, with the normal transient opening of the lower esophageal sphincter

that occurs with activities such as swallowing or belching, there is an excess

of refluxed gastric content. This reflux is enough to initiate sensory

activation, leading to symptoms such as heartburn or chest pain. Patients with

this form of reflux are unlikely to progress to more severe forms and may have

their symptoms controlled through medications such as proton pump inhibitors

and/or lesser therapies such as lifestyle changes. On the other hand, the more

severe form of GERD is one that allows far greater quantities of gastric

content, such as acid, bile, and pepsin, into the esophagus to a degree that

the normal squamous epithelium and other esophageal defense mechanisms are

inadequate to prevent tissue injury. These patients develop erosions,

ulceration, strictures, and/or meta plastic changes (Barrett esophagus). The

mechanisms that contribute to this form of GERD include a hypo tensive lower

esophageal sphincter, commonly in association with a sliding hiatal hernia, and

nocturnal reflux in which the esophagus sits relatively defenseless without

gravity or normal swallowing to help with clearance of refluxed caustic gastric

contents. When erosive esophagitis occurs, it does so distally, with more extensive

and proximal esophageal involvement increasing with greater quantities and

proximal movement of esophageal acid and bile exposure. For the purposes of

standardizing endoscopic findings in GERD, the Los Angeles Classification of

Erosive Esophagitis was developed (see table, above). The importance of this

classification lies not only in standardization but with determining treatment.

For example, once erosive disease occurs in GERD, particularly grade B and higher,

proton pump inhibitors are needed at the minimum to heal the esophagitis. With

high grades of injury, higher doses and sometimes fundoplication may be needed.

Also, because the mechanisms that lead to this degree of esophageal injury,

such as a large hiatal hernia and incompetent lower esophageal sphincter, are

not reversible, these patients need lifelong treatment with proton pump

inhibitors or fundoplication to prevent relapse of injury.