PSORIASIS

Psoriasis is an autoimmune disease that affects 1% to 2% of the U.S. population. There is a large regional variation in the incidence of psoriasis. Scandinavian countries have a much higher incidence than the rest of the world, and the Native American population has one of the lowest rates of psoriasis. Much has been learned about the pathogenesis of psoriasis, and dramatic advances in therapy have helped many patients. Psoriasis is grouped with the other papulosquamous skin diseases. It can cause not only skin disease but also joint disease. The total effect that psoriasis has on patients cannot be judged solely on the basis of skin involvement, because the disease has been shown to have pro-found psychological and social effects as well. There is no known cure for psoriasis, but research is moving forward, and new therapies are being developed.

|

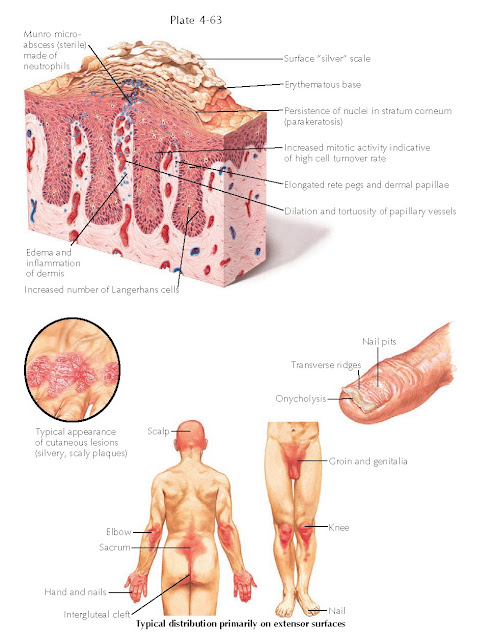

| HISTOPATHOLOGICAL FEATURES AND TYPICAL DISTRIBUTION OF PSORIASIS |

Clinical Findings: Psoriasis is a papulosquamous skin disease that can affect people at any

age of life. There is no gender predilection. Approximately 40% of affected

individuals have a family history of psoriasis. Most patients with early age at

onset tend to have a more severe course of disease. Psoriasis often starts with

silvery, ostraceous, scaly patches and plaques with a predilection for the

knees, elbows, and scalp. The term ostraceous scale refers to the oyster

shell–like appearance of the hyperkeratotic scale that is oriented in a concave

manner. The term rupioid scale is used to describe the psoriatic plaques

that appear to mimic the cone shape of limpet shells. A characteristic clinical

finding is that of Woronoff’s ring, the peripheral rim of blanching seen around

the early psoriatic plaques. Auspitz’s sign is another characteristic clinical

sign used to differentiate psoriasis from other rashes. It refers to the

pinpoint bleeding that occurs after the upper scale has been removed from a

psoriatic plaque. Woronoff’s sign is specific to psoriasis and most likely is

caused by localized vasoconstriction surrounding the area of the lesion, which

has an increased blood flow. There is a striking symmetry to the rash.

Psoriasis can have various skin morphologies. There are many well- recognized

clinical variants with distinctive clinical findings.

Psoriasis vulgaris is the most common form of

psoriasis encountered. It manifests with symmetrically located, silvery, scaly

patches and plaques on the scalp, knees, elbows, and lower back. Patients can

have a small amount of body surface area involvement, or they can have

widespread disease approaching near- erythroderma. The face is usually spared

from patches and plaques of psoriasis. Patients with a higher body surface area

of involvement tend to have a higher risk for development of psoriatic

arthritis and psoriatic nail disease. All patients with psoriasis exhibit the

Koebner phenomenon. Koebnerization of psoriasis occurs when a previously normal

area of skin is traumatized and psoriatic plaques develop within the

traumatized skin.

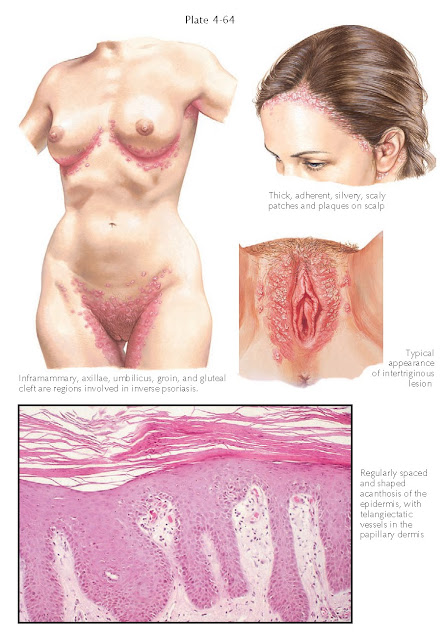

Inverse psoriasis is a well-recognized clinical

variant that manifests in intertriginous areas of the groin, gluteal cleft,

axillae, and umbilicus. The patches tend not to be as thick as in the other

forms, and the scale is fine. This is due to their location in occluded areas,

which have an increased amount of moisture and help to keep the scale to a

minimum. The patches can be bright red and are often misdiagnosed as a

cutaneous Candida infection. Inverse psoriasis is also symmetric in nature and can present

therapeutic challenges.

Guttate psoriasis is a variant of psoriasis that can

occur after an infection, most notably a streptococcal bacterial infection. The

guttate lesions develop soon after or during the infection and appear as tiny

teardrop-shaped patches with fine adherent scale. The word guttate means

“droplet,” and the lesions of guttate psoriasis appear as tiny droplets of psoriatic patches found generalized

over the skin, as if areas of psoriasis had developed within sprinkled water

droplets. Children with guttate psoriasis may have only one isolated episode

after a streptococcal infection and no evidence of psoriasis thereafter. Adults

with guttate psoriasis, on the other hand, almost always develop psoriasis

vulgaris at some later point.

Scalp psoriasis is a unique variant that occurs only

on the scalp. Patients complain of thick, scaly patches that itch and can cause

a dramatic amount of seborrhea. Most patients who present with localized scalp

psoriasis eventually develop areas of psoriasis elsewhere on their bodies.

Pustular psoriasis is a rare and distinctive form. It

can occur in patients with a preexisting history of psoriasis, or it can be the

initial presenting morphology. The diagnosis is straightforward in a patient

with a long- standing history of psoriasis who develops a pustular flare. The

most common reason for this is the rapid withdrawal of systemic

corticosteroids, for example, when a patient with psoriasis is prescribed

methyl- prednisolone for some unrelated condition, such as allergic contact

dermatitis due to poison ivy. The rapid decrease in the dose of the

corticosteroid can induce a pustular flare. The patches of psoriases develop

pin-point (1-2 mm) pustules that can coalesce into superficial pools of pus.

These patients are often ill appearing and can have associated hypocalcemia.

Patients presenting with pustular psoriasis without a preexisting history of

psoriasis pose a difficult diagnostic problem at first. The differential diagnosis

is among psoriasis, a pustular drug eruption, and Sneddon-Wilkinson disease. A

skin biopsy and clinical follow-up will eventually make the diagnosis clear.

|

| INVERSE PSORIASIS AND PSORIASIS IN THE GENITAL AREA |

Nail psoriasis is most often associated with severe

psoriasis vulgaris and psoriatic arthritis. It can occasionally be a solitary

finding. Oil spots, onycholysis, nail pitting, and variable amounts of nail

thickening can be present. Nail disease is refractory to most topical

therapies, and often systemic therapy is required to get a good clinical response.

Nail psoriasis is a marker for psoriatic arthritis, and patients with nail

psoriasis are at a higher risk for development of psoriatic arthritis.

Palmar and plantar psoriasis is another of the less

commonly seen clinical variants. It can manifest on the palms and soles as red,

scaly patches and plaques or as patches studded with a variable amount of small

pustules. This variant of psoriasis is more commonly found in females, and

smoking has been shown to make the clinical course worse.

Psoriatic erythroderma is a rare variant that is seen

as a sequela of steroid withdrawal or of other, undefined triggers. It

manifests with near-total redness of the skin. The redness is caused by massive

vasodilatation of the cutaneous vasculature, which can lead to high-output

cardiac failure. These patients are universally treated in the inpatient

setting.

Psoriatic arthritis can manifest in association with

psoriatic skin disease or as arthritis with nail findings. Patients typically present with an asymmetric oligoarticular

arthritis, a symmetric polyarticular arthritis, distal

interphalangeal–predominant disease, spinal spondylitis, or arthritis mutilans.

Arthritis mutilans is the rarest form of psoriatic arthritis, but it is life

altering and can lead to a devastating loss of function. Psoriatic arthritis is

considered to be a seronegative form of inflammatory arthritis.

Pathogenesis: Psoriasis is

an autoimmune disease caused by an abnormality within the cells of the immune

system. There is a genetic susceptibility, and the human leukocyte antigen

(HLA) Cw6 locus is the most commonly found (but not the only) susceptibility

factor in patients who develop psoriasis. The success of therapy with

cyclosporine, a medication that dramatically decreases T-cell function, was one

of the first clues to the

pathogenesis of psoriasis. Psoriatic patients given this medicine almost always

have rapid clinical improvement.

T-cell lymphocytes and dermal dendritic cells are the

most likely precursor cells to be the cause of psoriasis; they are both found

in increased numbers in psoriatic plaques. CD8+ T cells are the predominant

lymphocyte found within the epidermis; they contain the cutaneous lymphocyte

antigen (CLA) antigen on their cell surface. The CLA antigen is important

because it directs these cells into the skin. Many subsets of dermal dendritic

cells have been found within psoriatic plaques. Dendritic cells have been shown

to be potent stimulators of T cells, and they are believed to be required to

propagate the inflammatory reaction. These two cell types interact with each

other and change the local cytokine profile into one that is proinflammatory

and provides a milieu that is required for the development of the clinical

findings of psoriasis. What is still unknown is the initial stimulus that sets

off this cascade of events and how it is propagated and perpetuated.

|

| PSORIATIC ARTHRITIS |

Histology: Histological

examination of biopsy specimens of psoriasis vulgaris show regular psoriasiform

hyperplasia of the epidermis. Multiple normal-appearing mitotic figures are

seen within keratinocytes. Neutrophils are prominent within the stratum corneum

and within the lumen of the papillary dermal blood vessels. Mounds of

parakeratosis are seen in the stratum corneum and contain many neutrophils. The

papillary dermis shows a proliferation of ectatic capillary vessels with a

perivascular infiltrate made up of lymphocytes, Langerhans cells, and histiocytes.

Collections of neutrophils within the stratum corneum are called Munro

microabscesses. Kogoj microabscesses are similar collections of neutrophils

within the stratum spinosum. There is a decrease in the thickness of the

granular cell layer. With time, some of the tips of the rete ridges coalesce

and form thickened ends.

Pustular psoriasis shows varying amounts of

intraepidermal pustules; acanthosis and psoriasiform hyperplasia are not

prominent. Again, there are multiple dilated capillary blood vessels in the

papillary dermis.

Treatment: There is no

cure for psoriasis. Treatment should be based on the amount and location of the

psoriatic plaques and consideration of the psychological well-being of the

affected individual. Small areas in discrete locations can be treated with

topical corticosteroids, anthralin, tar compounds, or vitamin D or A analogues

or left alone without therapy. Ultraviolet therapy with natural sunlight,

narrow-band ultraviolet B light (UVB), or psoralen + ultraviolet A light (PUVA)

has been used with great success. Often, combinations of therapies are

implemented.

As the body surface area of involvement increases or

the psychological well-being of the individual is affected such that systemic

therapy is warranted, many agents are available to treat the psoriasis.

Phototherapy with narrow-band UVB or PUVA has been used for decades with excellent results. In the long term, these

therapies increase the patient’s risk of developing skin cancers, and lifelong

dermatologic follow-up is required.

Oral systemic agents are also used for moderate to

severe psoriasis. Methotrexate taken on a weekly basis has been used for years.

Oral cyclosporine has been used with great success for erythrodermic and

pustular psoriasis. Its use is limited to 6 to 12 months because of

nephrotoxicity. Many biological agents have become available over the last decade. These medications are

given by subcutaneous, intramuscular, or intravenous injection. They include

etanercept, alefacept, adalimumab, infliximab, and ustekinumab. All of these

agents have had excellent response rates. They are all considered to be

immunosuppressive, and patients taking these medications need close clinical

follow-up, because they are at increased risk for infections and possibly for

systemic cancers, such as lymphoma, after years of use.