INJURIES TO THE FINGERTIP

As the sensory input to the upper extremities, the fingertips encounter

their environment first and are often unfortunately injured. Whether it be on a

sporting field or in the workplace the fingertips are subject to cuts, burns,

punctures, and sudden impact and crushing injuries. It is of paramount

importance to try and restore the fingertips for optimal hand and upper

extremity function.

Fracture Of The Distal Phalanx And Subungal Hematoma

Impact injury to the fingertip often causes a hematoma

due to bleeding from either the nail bed or an underlying fracture of the

distal phalanx. This hematoma is often trapped under the nail plate, causing

significant pressure to build up and resultant pain. When the pain is

significant, this can be relieved by drainage of the hematoma. It is important

to obtain a radiograph to rule out a fracture because, once drained, this hole

in the nail plate becomes a portal to an infection in the distal phalangeal

bone if not cared for appropriately. An old treatment of heating a paperclip

under a flame does not properly sterilize the metal tip, and therefore only a

sterile needle should be used. A 22-gauge needle can be used by hand to

adequately drill a small perforation in the nail plate and provide evacuation

of the hematoma. The patient should be given an antibiotic if the injury

dictates, and the nail plate should be kept clean. A short splint blocking the

distal interphalangeal joint will allow for pain relief and protection of the

underlying injured fingertip.

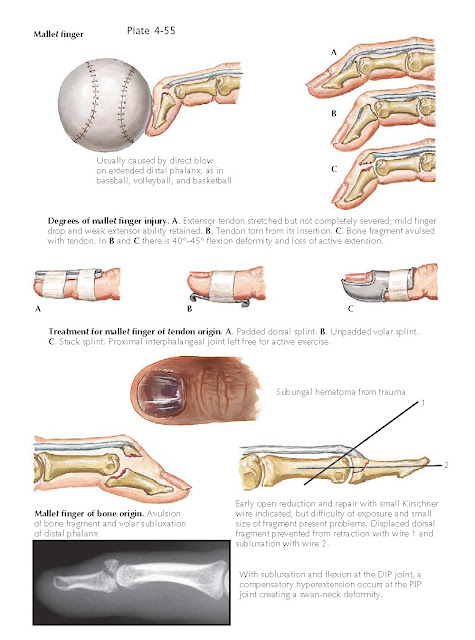

Mallet Finger

Hyperflexion that disrupts the extensor mechanism of

the distal phalanx causes a mallet finger, an injury common in ball players. Three types of injury occur:

stretching of the extensor tendon past its elastic limit, which causes multiple

interstitial tears; complete disruption of the extensor tendon; and avulsion

fracture of the base of the distal phalanx. The patient with mallet finger

often does not appreciate the severity of the injury, and even the examining

physician may not recognize the injury. The acute signs are tenderness over the

dorsum of the distal interphalangeal joint and inability to actively extend the

distal phalanx.

Treatment consists of splinting the distal

interpha-langeal joint in extension. The splint should be placed on the dorsal aspect during the day so the volar

surface of the finger can still be used in opposition; it is worn continuously

for 6 to 8 weeks, then only at night for an additional 3 to 4 weeks. A palmar

splint is used at night to relieve the continuous pressure on the dorsal skin.

The patient should be warned that splinting may cause some skin loss over the

dorsum of the distal phalanx and that full extension may never be regained.

Mallet finger with avulsion of a large bone fragment

may be associated with volar subluxation of the distal interphalangeal joint. Surgical repair, although

indicated, is difficult because the blood supply to the skin is poor, the

fragment is quite small, and a good reduction with Kirschner wires is often

difficult to maintain. Therefore, a dorsal blocking pin is more effective to

prevent proximal retraction of the tendon-bone complex. A pin across the joint

ensures concentric reduction and go d soft tissue healing to avoid recurrent

subluxation.