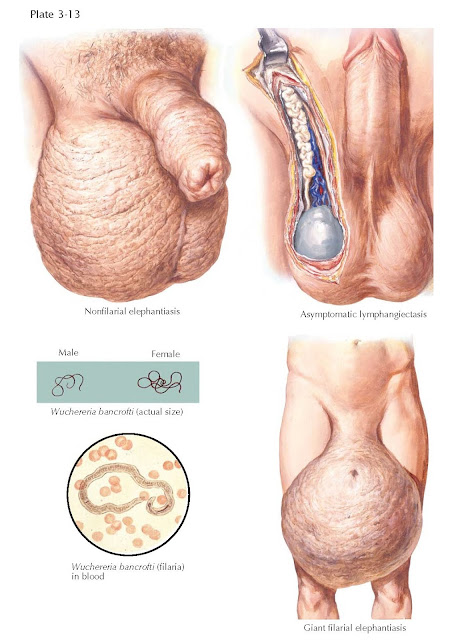

ELEPHANTIASIS

Filarial elephantiasis of

the scrotum presents as diffuse scrotal enlargement from hypertrophy and

hyperplasia of the subcutaneous tissues and epidermis, which become leathery,

coarse, and dry. Sebaceous glands are usually destroyed. The consistency of the

leathery skin is that of nonpitting edema. The scrotum varies in size from

slight enlargement to becoming monstrous in size, with the scrotum touching the

ground and weighing as much as 200 pounds. The condition is indigenous to

tropical areas. Filarial elephantiasis is caused by a nematode, Wuchereria

bancrofti (90%), and is transmit- ted to man by certain mosquito species (Culex,

Aedes, and Anopheles). Other thread-like parasitic worms such as Brugia

malayi (10%) and Brugia timori (1%) may also cause elephantiasis.

The adult worms in man are found in lymphatic channels and in subcutaneous

tissues; the larval forms usually enter the bloodstream between the hours of

midnight and 2 am. These microfilariae produce no general symptoms except those

associated with obstruction of lymphatics. Scrotal elephantiasis is a late

sequela of filarial infection and results from lymphatic obstruction. Secondary

bacterial infections can accentuate the process. Usually, a history of repeated

episodes of lymphangitis and lymphadenitis associated with fever, malaise,

rash, and tender lymph nodes after inoculation is obtained. With each episode

of diffuse enlargement and swelling, the regression and healing is less

complete. Superficial lymphatics may become dilated, rupture, and exude lymph.

Filariasis may begin as an

insidious condition known as “lymph scrotum,” which is characterized by a mild

enlargement of the scrotum along with cutaneous lymphatic ectasia. Three other

presentations have been described with filariasis. The first is somewhat similar

to lymph scrotum but involves the spermatic cord, which feels like soft,

compressible vessels. In another presentation, the spermatic cord contains

thick, rubbery masses, which represent a late fibrous reaction following

lymphangitis. In this presentation, fibrous nodules, distinct from the vas

deferens, are palpated throughout the spermatic cord. The third type of

presentation, called “mumu,” was observed during World War II as acute swelling

and edema of the spermatic cord that gradually subsides after individuals leave

an endemic area. This may represent an allergic reaction that develops

following filarial inoculation.

Although positive skin tests

and DNA polymerase chain reactions (PCRs) can detect filarial DNA and indicate

disease, the definitive diagnosis is made by finding the microfilariae in the

peripheral blood at night after filtration through micropore membrane filters.

This can also quantify the load of microfilariae. However, once lymphedema

develops, the microfilariae are absent in peripheral blood. Specific drug therapy

involves diethylcarbamazine (microfilaria and adult worms), ivermectin (microfilaria), albendazole (adult filarial worms), and

possibly even doxycycline. Once lymphedema develops, there is no cure but

reducing inflammation, and surgical removal of the elephantiasic genital tissue

may help in selected cases.

Alternatively, elephantiasis

may occur in the absence of parasitic infection. This nonparasitic form of

elephantiasis is known as nonfilarial elephantiasis or “podoconiosis,” and

occurs in high frequency in northern Africa. Nonfilarial elephantiasis is

thought to be caused by persistent contact with irritant

soils, or from lymphedema, lymph obstruction, or lymphangitis from a wide

variety of causes, including infection. This elephantiasis may occur as a

result of local disorders such as scrotal fistulae, or following inguinal

lymphadenectomy, metastatic carcinoma, or inguinal lymphangitis from syphilis,

lymphogranuloma venereum, tuberculosis, or granuloma inguinale. Treatment is

aimed at eradication of infection and

supportive care for the

enlarged scrotum.