DEFORMITIES OF THE METACARPOPHALANGEAL

JOINTS

Arthritic diseases may affect any joint, but their

effect on the hands can be especially devastating. The disease process attacks

the joints, ligaments, and tendons, causing painful and disabling deformities.

Fortunately, developments in joint reconstruction and replacement have made it

possible to restore hands deformed by crippling arthritis to a nearly normal

appearance and useful function.

Ideally, arthroplasty should produce a joint that is

pain free, mobile, stable, and durable. Four methods of reconstruction for

arthritic joints of the hand have emerged: arthrodesis, resection interposition

arthroplasty, resurfacing joint replacement, and flexible implant resection arthroplasty.

Arthrodesis works very

well for the thumb at the metacarpophalangeal joint level and for the lesser

fingers at the proximal and distal interphalangeal joint level, but lack of

motion is debilitating in the lesser fingers at the metacarpophalangeal joint

level and rarely used.

Resection interposition arthroplasty can improve motion by shortening skeletal structures, lengthening soft

parts, providing new gliding surfaces, and allowing the development of a new

supportive fibrous joint capsule. The chief disadvantage of the procedure in

the metacarpophalangeal joints is the unpredictability of results. Resurfacing

joint replacement has proved successful in knee and hip joints, but early

results in finger joints have been mixed because of dislocation, bone resorption,

and implant loosening. More recently, newer designs are proving useful in

patients with osteoarthritis and early rheumatoid arthritis where the soft

tissue balance is

still relatively normal.

In flexible implant resection arthroplasty, a

flexible silicone implant is used as an adjunct to resection arthroplasty. This

method was devised in 1962 and has been used successfully in several hundred

thousand patients. This discussion emphasizes the techniques of implant

resection arthroplasty.

The basic concept of flexible implant resection

arthroplasty can be summarized as “bone resection + implant + encapsulation =

functional joint.” The flexible implant acts as a dynamic spacer, maintaining

internal alignment and spacing of the reconstructed joint and supporting the

capsuloligamentous system that develops around it. The joint is thus rebuilt

through a healing phenomenon called the “encapsulation process.” Because the

capsuloligamentous system around a new joint is adaptable, a functional balance

of mobility and stability can

be obtained. This allows for realignment of severely dislocated and angulated

joints after the significant bony and soft tissue resection needed in severe

rheumatoid deformities. Postoperative mobilization is tailored to the amount of

instability present after reconstruction; delay in mobilization increases stability.

This is typically acceptable as the flexors greatly over- power the extensors

and prolonged immobilization in extension is rapidly overcome, giving a stable,

mobile grip. Soft

tissue balance is key to preventing the recurrence of deformity and to implant

breakage, dislocation, and failure.

General Considerations

The candidate for arthroplasty must be in good general

condition. Skin cover and neurovascular status must be adequate. The elements

necessary to restore a functioning musculotendinous system and sufficient

bone stock to receive and support the implant must be available. In certain

patients with progressive rheumatoid arthritis who have insufficient bone stock

to support the implant, a simple resection arthroplasty or arthrodesis with a

bone graft is preferable. Surgery is also contraindicated if postoperative hand

therapy is not available or adequate.

Proper staging of the reconstructive procedures is

important in planning the treatment program. Procedures in the upper limbs

should be delayed in patients who also need lower limb reconstruction that will

necessitate the use of crutches. After hand reconstruction, patients should

avoid excessive manual labor and awkward hand weight bearing when using crutches.

The special platform type of crutch is recommended.

In deformities of the metacarpophalangeal joint associated

with severe wrist involvement, the wrist should be treated first. In the

patient with rheumatoid arthritis, tendon repair and synovectomy of tendon

sheaths must precede arthroplasty of the metacarpophalangeal joints by 6 to 8

weeks. If both metacarpophalangeal and proximal interphalangeal joints are

involved, the metacarpophalangeal joint is usually treated first or

simultaneously if only operating on one or two metacarpophalangeal joints. In

swan-neck deformity, the metacarpophalangeal and proximal interphalangeal

joints are reconstructed at the same stage. In boutonnière deformity, the

proximal interphalangeal joint is reconstructed first. Tendon imbalances and

joint misalignment must be corrected. Implant arthroplasty for both the metacarpophalangeal

and proximal interphalangeal joints of the same digit is usually avoided if

possible.

Several procedures can be performed during one operation, depending on the time available. Surgery

for the thumb, proximal interphalangeal and distal inter-phalangeal joints,

wrist, and, occasionally, the elbow joint can often be combined. A limb

procedure should be limited to no more than 2 hours, and an axillary or

supraclavicular block is recommended if the tourniquet time exceeds 112 hours.

Small joints may also be injected with corticosteroids or other agents during

surgery.

Deformities Of Finger Joints

In the normal hand, a delicate balance exists among

the muscles and tendons and the bones and joints through which they interact. The hand has three functional

arches, one longitudinal and two transverse. The proximal transverse arch

crosses the carpal area, with its center at the capitate. The distal transverse

arch is formed by the metacarpal heads and is centered on the head of the third

metacarpal. The digits make up the longitudinal arches, each with its apex at the metacarpophalangeal

joint.

In rheumatoid arthritis, this balance among the muscles,

tendons, and bones is compromised as the inflammatory synovial membrane grows

over the surface of the cartilage, into the ligamentous attachments, and into and around the tendons. The result is capsular

distention, destruction of cartilage, subchondral erosions, loosening of

ligamentous insertions, impaired tendon function, and, finally, joint dis-

organization, subluxation, and dislocation. A break in the longitudinal arch

system causes collapse deformities of the multiarticular structure of the hand,

disturbing the stability and balance necessary for prehension. Use of the hand

in daily activities (functional adaptation) causes further deformity.

Deformities Of Metacarpophalangeal Joint

The metacarpophalangeal joint is a key element in finger

function. This joint not only flexes and extends but also abducts and adducts;

it also has some passive axial rotation. The index finger can pronate up to 45

degrees.

Rheumatoid arthritis commonly involves the metacarpophalangeal

joints, resulting in increased ulnar deviation of the fingers, subluxation of

extensor tendons, and palmar subluxation of joints (see Plate 4-21). The flexor

tendons enter the fibrous sheath at an angle, exerting an ulnar and palmar pull

that is resisted in the normal hand. When the rheumatoid process distends and

weakens the capsule and ligaments of the metacarpophalangeal joint, the forces

generated by the long flexor tendons across the sheath during flexion may

elongate these supporting structures. Resistance to the deforming pull of the

tendons is gradually lost, and the sheath inlet and tendons are displaced in

distal, ulnar, and palmar directions. Eventually, the base of the proximal

phalanx moves ulnarly and palmarly. The intrinsic muscles, which normally form

a bridge between the extensor and flexor systems and provide direct flexor

power across the metacarpophalangeal joint, can also become deforming elements

once the disease has lengthened the restraining structures of the metacarpophalangeal

joint.

Increased mobility of the fourth and fifth metacarpals,

common in rheumatoid arthritis, results from loosening of ligaments at the

carpometacarpal joints and dysfunction of the extensor carpi ulnaris tendon

(ulnar head syndrome). Flexion of the metacarpophalangeal joints increases the

breadth of the transverse arch of the hand, which pulls the extensor tendons in an ulnar direction through the juncture tendons. The

extensor tendon expansions (hoods) are loosely fixed and vulnerable to

disruption. Ulnar subluxation of the extrinsic extensor tendons compromises the

balance of the intrinsic extensor tendons, which in turn increases the tendency

for palmar subluxation and ulnar deviation.

Factors that exacerbate ulnar deviation include (1)

the normal mechanical advantage of the ulnar intrinsic muscles, (2) the asymmetry

and ulnar slope of the metacarpal heads of the index and middle fingers, (3)

the asymmetry of the collateral ligaments, (4) the ulnar forces applied on

pinch and grasp, and (5) the postural forces of gravity. Wrist deformities and

rupture of the extensor

tendons play a secondary role in aggravating the joint disturbances.

Pronation deformity of the index finger is common in

the rheumatoid hand. In the normal hand, pinch between the thumb and index

finger requires a slight supination of the index finger so that the palmar surfaces can meet. In pronation deformity, the less useful lateral surfaces are

opposed. During pinch, pronation deformity is seen in all three digital joints,

but it is more pronounced in the metacarpophalangeal joint. Arthroplasty of

this joint should include reconstruction of the capsuloligamentous and

musculotendinous systems.

Surgery For Metacarpophalangeal Joint

Flexible implant resection arthroplasty of the metacarpophalangeal

joints is carried out for deformities due to rheumatoid arthritis and trauma,

with radiographic evidence of joint destruction too great to support resurfacing

implants or subluxation greater than 25%, ulnar deviation not correctable with

soft tissue surgery alone, and contraction of the intrinsic and extrinsic

musculature and ligamentous system.

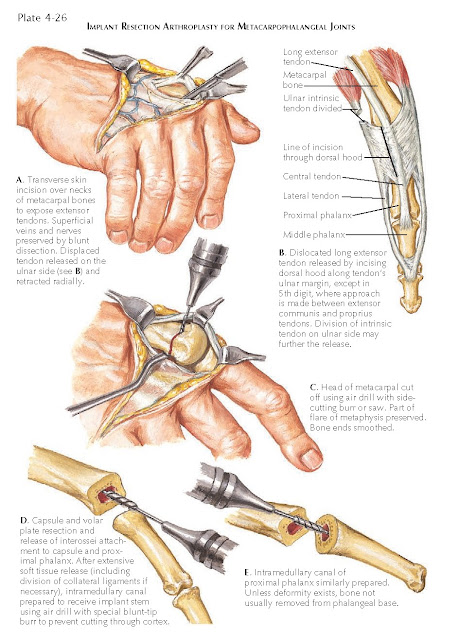

The surgical technique for implant resection arthroplasty

for the metacarpophalangeal joint is shown on Plates 4-26 to 4-28. Soft tissue

release must be complete to obtain an appropriate joint space. The ulnar

collateral ligament is incised at its phalangeal insertion in all fingers; if

severely contracted, it is excised with the palmar ligament (plate). The ulnar

intrinsic tendon, if tight, is sectioned at its myotendinous junction and the

abductor digiti minimi is released.

Reconstruction of the radial collateral ligament is

done for index and middle fingers. The radial collateral ligament and related

structures are reattached proximally to the metacarpal neck and distally to the

proximal phalanx through small drill holes. The radial half of the palmar plate

and the preserved radial capsule are included in this repair. The ulnar edge of

the capsule is sutured to the distally released ulnar collateral ligament.

Sutures are placed before the implant is inserted and tied with the finger held

in supination and abduction. Although the procedure seems to slightly limit

flexion of the metacarpophalangeal joint, this is out-weighed by increased

lateral and vertical stability and better correction of the pronation deformity.

After the procedure, a voluminous conforming dressing,

including a palmar splint, is applied with the metacarpophalangeal joints in 30

degrees of flexion and slight radial deviation. During the postoperative

period, the limb must be elevated. A meticulous postoperative therapy program

is usually started 3 to 5 days after surgery and consists of static splinting

of the metacarpophalangeal

joints for 4 weeks with free movement of the proximal and distal

interphalangeal joints followed by mobilization of the metacarpophalangeal

joints in a radial deviation support brace. Full hand night splinting in a

slightly overcorrected position is used for 6 months.