DEFORMITIES OF INTERPHALANGEAL

JOINT

The collateral ligament system and the flexor and extensor tendons play

an important role in maintaining the normal configuration of the proximal

interphalangeal joint. The distal interphalangeal joint acts as a simple hinge

but is very important for balancing the proximal interphalangeal joint, and

hyperextension or flexion (mallet) deformity can cause boutonnière or swan-neck

deformities, respectively. The rheumatoid process compromises the normal

anatomy of the joint and may lead to joint stiffness, with or without lateral

deviation, or to collapse deformities, most notably boutonnière and swan-neck

deformities. Mallet finger is not common in rheumatoid arthritis but is common

in osteoarthritis. Limited joint movement may result from articular factors

(adhesions and disorganization of the joint), periarticular factors (adhesions

or laxity of ligaments), or tendinous factors (synovial invasion of the flexor

tendons and adhesions).

Collapse deformities of the three-joint system of the digit

are characterized by hyperextension of one joint and reciprocal flexion of

adjacent joints. The deformity occurs when the balance between the tendon and

ligament systems is compromised. Axially applied forces further aggravate the

deformity, establishing a cycle of deforming forces.

Boutonnière Deformity

This condition is characterized by flexion of the

proximal interphalangeal joint and hyperextension of the distal interphalangeal

joint (see Plate 4-31). In rheumatoid arthritis, causes of boutonnière

deformity include (1) capsular distention

of the proximal interphalangeal joint; (2) lengthening of the central long extensor

tendon, with lack of extension in the middle phalanx; (3) lengthening of the transverse fibers; (4) palmar

subluxation of the lateral bands, which become flexors of the proximal interphalangeal

joint; (5) increased extensor pull on the distal phalanx; (6) self-perpetuating collapse

deformity; and (7) soft tissue contracture, joint stiffness, and

disorganization.

Swan-Neck Deformity

The term swan-neck deformity refers to hyperextension

of the proximal interphalangeal joint and flexion of the distal interphalangeal joint (see Plate 4-31). In

rheumatoid arthritis, the deformity may result from (1) synovitis of the flexor

tendon sheath, which causes difficulty in initiating or completing flexion of

the interphalangeal joint; (2) increased flexor pull at the metacarpophalangeal

joint; (3) increased pull of the intrinsic muscles to the central tendon; (4)

loosened attachments of the palmar ligament and accessory collateral ligaments

of the proximal interphalangeal joint; (5) hyperextension of the proximal

interphalangeal joint; (6) stretching of the oblique retinacular ligaments; (7)

dorsal subluxation of the lateral bands, which become extensors of the proximal

interphalangeal joint; (8) pull of the flexor digitorum profundus tendon, which

flexes the distal interphalangeal joint; and (9) joint disorganization and

subluxation. Other factors that increase the mechanical advantage of the

extensor pull and accentuate the deformity include palmar subluxation of the

metacarpophalangeal or wrist joint and contracture of the intrinsic muscles secondary to chronic flexion deformity of the

metacarpophalangeal joint. In osteoarthritis, deformity typically starts with a

stiff flexion deformity of the distal interphalangeal joint.

Deformities Of Distal Interphalangeal Joint

In osteoarthritis and rheumatoid arthritis,

deformities of the distal interphalangeal joint are usually secondary to

collapse deformities. Specific deformities resulting from synovial invasion are

uncommon; however, loosening of the distal attachment of the extensor tendon

may cause a mallet or drop finger. Loosening of the collateral ligaments,

erosive changes in the subchondral bone, and cartilage destruction in combination

with external forces applied during daily activities may lead to joint

instability. Complete joint destruction may also occur secondary to the severe

resorptive changes seen in arthritis mutilans.

Surgery For Proximal Interphalangeal Joint

In swan-neck deformity, flexor synovitis is treated

first. If the articular surfaces are preserved, hemitenodesis of the flexor digitorum superficialis tendon to the base

of the middle phalanx can be done at the same time to check the hyperextension

deformity of the proximal interphalangeal joint. Usually, it is not necessary

to lengthen the central slip in release of the swan-neck deformity. It is

important to obtain adequate release of the dorsal capsule, collateral

ligaments, and palmar plate. A 10-degree flexion contracture (or greater) of the proximal

interphalangeal joint should be obtained and associated deformities of the

contiguous joints corrected.

In a mild flexible deformity in weak hands, dermadesis

is indicated: an elliptic wedge of skin (sufficient to create a 20-degree

flexion contracture) is removed from the flexor aspect of the proximal interphalangeal joint, preserving the

underlying vessels and nerves. If the articular surfaces are inadequate,

however, fusion of the proximal interphalangeal joint is preferred. Implant

arthroplasty is rarely indicated.

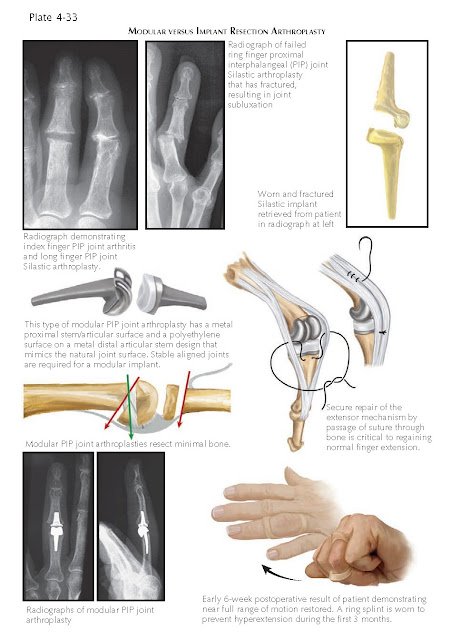

Treatment of arthritic deformities of this joint

includes realignment of the longitudinal arch of the digit. The joint can be

treated by arthrodesis, resurfacing arthroplasty, or resection implant arthroplasty.

Resurfacing of the proximal interphalangeal joint is indicated for painful,

degenerative, or posttraumatic deformities with destruction. When subluxation

of the joint that cannot be corrected with soft tissue reconstruction alone or

significant bone loss exists, implant resection arthroplasty is indicated. For

deformities of the proximal interphalangeal joints of both the index and long

fingers with osteoarthritis or early rheumatoid arthritis in a young person who

performs heavy labor, the proximal interphalangeal joint of the index finger is

fused in 20 to 40 degrees of flexion, and resurfacing or resection implant

arthroplasty is performed for the proximal interphalangeal joint of the middle

finger. The more stable index finger can be used in pinch, and the more

flexible long finger can be used in grasp. Flexion of the proximal

interphalangeal joints in the ring and little fingers is very important for

grasping small objects, and function should be restored if possible.

Good results require adequate release of joint contractures.

The collateral ligaments are left intact when-ever possible and if released

they should be released on both sides to prevent pivoting instability on the

intact side. Rebalancing and postoperative capsuloligamentous healing will

stabilize the joint when the postoperative protocol below is utilized. If the

joint is severely contracted, more bone is removed, or if too great and the

joint cannot reduced, an implant resection arthroplasty is used, allowing for even more bone resection. If the

contracture persists, the palmar plate and collateral ligaments may be incised

proximally or distally, as needed. The collateral ligaments are not required to

be repaired. Resurfacing arthroplasty may be placed either press-fit because they

have a bone ingrowth surface or cemented if a tight fit cannot be achieved.

Importantly, the central tendon is advanced slightly distal on the middle phalanx, which ensures

full extension postoperatively. A coexisting mallet deformity of the distal

interproximal joint must be corrected at the time of surgery to prevent a

swan-neck deformity.

The hand is dressed as in metacarpophalangeal joint

surgery, and 2 or 3 days after surgery, hand-based thermoplastic splints are applied with the finger in 0 degrees of

flexion for 3 to 4 weeks. Motion is initiated under supervision, and flexion is

gradually increased after 3 weeks as long as full extension can be obtained.

The resting splint can be applied slightly to the radial or ulnar side of the

digit to correct any residual tendency to deviate; it is worn at night and

between exercise periods until adequate healing occurs.

In an alternative approach, the central tendon is pre-

served and the exposure is volar, releasing the cruciate pulley, displacing the

flexor tendons, releasing the volar plate, and preserving the extensor tendon

insertion. Postoperative motion is immediate and preferred for resection

implant arthroplasty. However, visualization and correction of soft tissue and

bony deformity for resurfacing arthroplasty is more difficult to achieve and

may be incomplete.

Implant resection arthroplasty for proximal interphalangeal

joints with collapse deformity requires adjustment of the tension of the

central tendon and lateral bands as mentioned earlier. Compared with the

lateral bands, the central tendon is relatively tight in the swan-neck

deformity and must be released, while in the boutonnière deformity, the central

tendon is relatively loose and must be tightened.

Implant resection arthroplasty for boutonnière

deformity is accompanied by reconstruction of the extensor tendon mechanism.

The collateral ligaments are reefed or reattached to bone as needed. After

surgery, extension of the proximal interphalangeal joint and flexion of the

distal interphalangeal joint must be maintained. The proximal interphalangeal

joint is immobilized in extension with a padded aluminum splint for 3 to 6

weeks; the distal joint is allowed to flex freely. Active flexion and extension

exercises are started 3 to 4 weeks after surgery, and a splint should be worn

at night for about 10 weeks.

Surgery For Distal Interphalangeal Joint

If the distal interphalangeal joint is unstable,

subluxated, or deviated or if there is articular damage, arthrodesis is the

treatment of choice. Contractures of the joint may be treated with soft tissue

release and temporary fixation with a Kirschner wire to allow some useful residual movement.

Slight flexion movement of the distal interphalangeal joint is very important

in finely coordinated activities, but if movement at the proximal

interphalangeal joint is good, fixation in a functional position is acceptable.