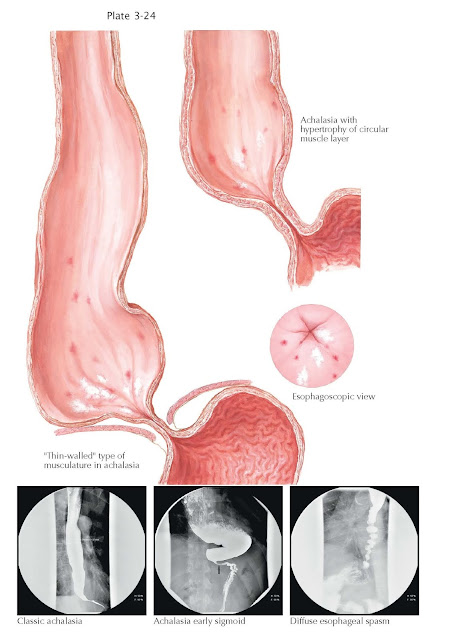

Achalasia and

Diffuse Esophageal Spasm

Achalasia is an uncommon disease occurring in 1:10,000 to 1:100,000 people. It

results from neurodegeneration of the myenteric plexuses in the esophageal body

and lower esophageal sphincter, leading to esophageal aperistalsis and

incomplete opening of the lower esophageal sphincter. Whereas the former

results from a lack of excitatory input to stimulate peristalsis, the latter

occurs from decreased nitric oxide mediated inhibitory input, leaving the

sphincter in a baseline excitatory state with failure to relax in response to

deglutition.

The initiating event in the pathophysiology remains unclear, but

both genetic predisposition and postviral autoimmune mechanisms have been

described. Clinically, it is a slow progressive process often masquerading as

reflux and typically with a long delay in diagnosis. Without effective

treatment, the process continues with progressive dilation of the esophagus, at

times, to massive pro portions with compression of adjacent structures such as

the lung and trachea. Classic symptoms of achalasia are dysphagia to liquids

and solids, regurgitation, chest pain, and weight loss. Achalasia patients,

however, often learn to adjust their lifestyle to the disease and present with

more subtle accommodating symptoms such as slow eating and stereotactic

movements with eating, such as sitting up straight or walking during a meal.

These maneuvers physiologically increase the longitudinal muscle tone. The

diagnosis is made by a combination of compatible symptoms, imaging (radiography

and/or endoscopy), and esophageal manometry. Imaging demonstrates a range of

findings depending on the severity of the disease. In early stages, a

nondilated esophagus with a difficult to pass or incompletely opening lower

esophageal sphincter may be seen on endoscopy or radiography. As the disease advances,

esophageal dilation is more easily appreciated, often with retained saliva and

food present despite prolonged fasting. In the most advanced stages, the

esophagus may elongate and dilate similar in appearance to the colon in a

process described as “sigmoidization.” Without the ability to alter the

underlying neural injury, therapy is aimed at pharmacologic or mechanical

disruption of the lower esophageal sphincter to at least allow gravity to

facilitate passage of the bolus into the stomach. A simple but relatively

shortterm treatment is endoscopic injection of botulinum toxin into the lower

esophageal sphincter. Pharmacologically, this suppresses cholinergic

stimulatory activity and lowers the lower esophageal sphincter pressure.

Mechanical therapies include endoscopy dilation with a highpressure pneumatic

balloon to rip sphincter muscle fibers or more precise cutting of the sphincter

(myotomy) through a surgical approach. Recently, the latter has been performed

completely through endoscopy (peroral endoscopic myotomy) by tunneling through

the esophageal submucosa and then incising the inner circular layer of the

muscularis propria of the lower esophageal sphincter. Longterm results are not

available yet for this novel approach. In severely advanced achalasia with

sigmoidization, esophagectomy may be needed. Finally, there is an increased

risk of esophageal squamous cell cancer in patients with longstanding

endstage disease. The pathophysiology of diffuse esophageal spasm is

likely similar to that of achalasia. The pathophysiology, however,

reflects a more pronounced form of esophageal disinhibition. Specifically, it

is manifested by an incompletely relaxing lower esophageal sphincter but also a

shorter time interval from the onset of deglutition to lower esophageal

sphincter relaxation (decreased distal latency) and hypertensive esophageal

contractions. These patients have dysphagia and/or severe episodic chest pain.

Radiographically, a “corkscrew” esophagus may be seen. Treatment is similar to that

for achalasia, but the response rate of symptoms, particularly chest pain, is

not as robust when compared with the response of dysphagia in achalasia. As a

result, additional treatment to control the chest pain is often needed. The

treatments are aimed at decreasing esophageal muscle pressures (e.g., with

anticholinergic or nitric oxide enhancing medications) or reducing esophageal

sensation (e.g., with lowdose tricyclic antidepressants). The number of cases

of diffuse esophageal spasm that remain stable or progress

to more typical forms of achalasia is variable.