LARYNGEAL AND TRACHEAL STENOSIS

The unique anatomy and

delicate tissues of the larynx and trachea predispose these sites to scarring

and stenosis in response to injury. Some of the more common causes include

prolonged endotracheal intubation, long-term tracheostomy, bacterial or viral

infection, systemic inflammatory conditions, neoplasia, and trauma. In many

cases, the stenosis is a relatively late sequela of the initial pathologic

process and may not be recognized until it progresses to the point of

symptomatic airway compromise (stridor or dyspnea) or impaired laryngeal

function (hoarseness).

Laryngeal

stenosis may occur at any level within the larynx. Supraglottic and glottic

stenosis are usually a result of external trauma or prolonged intubation but

are also seen with caustic ingestions, inhalation burns, and postsurgical

scarring. Subglottic stenosis is the most common form of laryngeal stenosis.

Prolonged endotracheal intubation can damage the thin inner perichondrium of

the cricoid cartilage, leading to circumferential scarring and cicatrix

formation. Long- term tracheostomy tubes can also cause subglottic stenosis as

a result of superior migration of the tube and ensuing destruction of the

cricoid ring. Other common causes of subglottic stenosis include

laryngopharyngeal reflux, Wegener granulomatosis, and a congenital form seen in

young children. When a specific cause cannot be identified, the term idiopathic

subglottic stenosis (ISS) is used. It is likely that many cases of ISS are

caused, at least in part, by unrecognized laryngopharyngeal reflux or autoimmune

disorders.

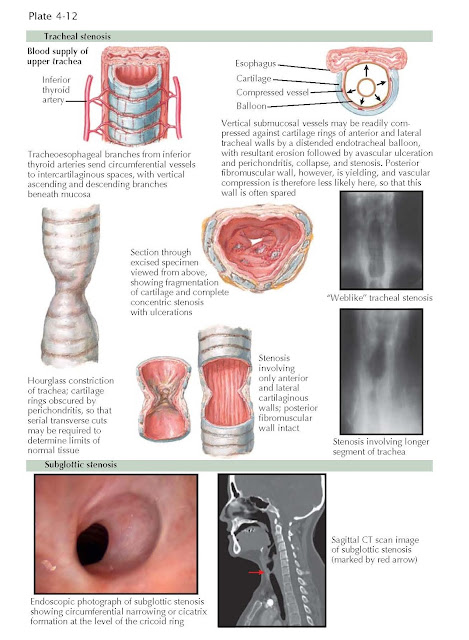

Tracheal

stenosis is a potentially devastating sequelae of prolonged endotracheal

intubation and tracheostomy in patients with respiratory failure requiring

cuffed tubes for mechanical ventilation. In the anterior and lateral tracheal

walls, the vertical blood vessels that course between the mucosa and the

cartilage rings may be readily compressed by a distending cuff or balloon.

Decreased blood supply leads to perichondritis, avascular necrosis, and

fragmentation of the tracheal cartilage. The resultant stricture often has a

triangular configuration on transverse section because of anterior weakening of

the cartilaginous arch with lateral wall collapse. Posteriorly, the membranous

trachea is more pliable, and the vascular supply is less likely to be

compressed. Thus, in about 50% of cases of postintubation or post- tracheostomy

balloon stenosis, the posterior tracheal wall is spared.

The

characteristics and extent of tracheal stenosis can be demonstrated

radiographically with traditional tomography in the frontal and lateral

projections or with computed tomography (CT) images in the coronal and sagittal

planes. The stenotic segment may be narrow and weblike, involving only one

tracheal ring, or it may be longer, involving two to five tracheal rings with

tapering margins. If the affected segment is thin or pliable, obstruction may

only occur with inspiration or expiration (tracheomalacia), depending on

whether the affected segment is extrathoracic (neck) or intrathoracic (thorax),

respectively. Tracheomalacia may result in greater functional impairment than

is apparent radiographically. If dynamic collapse is suspected, flow- volume loops

demonstrating reduced inspiratory or expiratory flow or fiberoptic bronchoscopy

demonstrating inspiratory or expiratory collapse may be useful diagnostic

tools. In some cases, multiple stenoses may occur, especially after the use of

tubes of different lengths or tubes with double cuffs.

Postintubation

and posttracheostomy balloon steno- sis remains a serious problem despite the

advent of low-pressure cuffs and increased vigilance in the clinical care

setting. It has been recommended that the cuff be deflated at intervals to avoid

an excessively prolonged compression of the tracheal mucosa. The problem with this method

is that the cuff may not empty completely, and if it is reinflated with the

minimal fixed volume of air recommended for filling, overinflation may occur.

Proper cuff pressures are best achieved by inflating under auscultatory control

until there is no leakage of air with positive-pressure ventilation. If

stenosis develops despite these measures, surgery in the form of endoscopic

laser incision and dilatation or tracheal resection with anastomosis may be necessary.