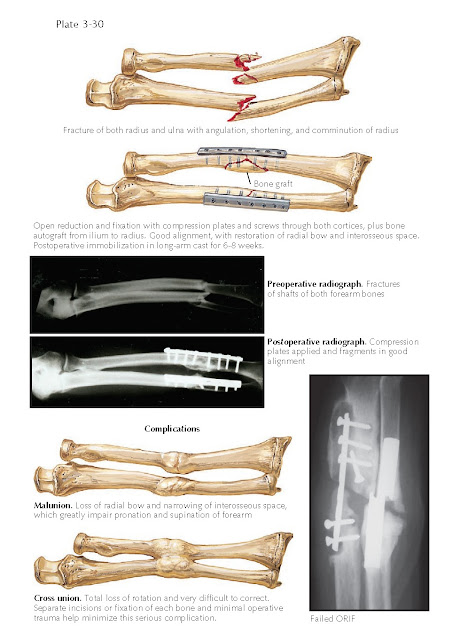

FRACTURE OF BOTH FOREARM BONES

Fractures of the shafts of the radius and ulna are usually significantly

displaced and are often comminuted because of the great force needed to break

these strong bones. Anatomic reduction of the fractures, with full restoration

of both the length and the bow of the radius, is essential to maintain maximal

function of the forearm. Even when anatomic reduction is achieved, some

long-term loss of supination and pronation may occur.

ORIF of fractures of both forearm

bones is performed through separate incisions, maximizing the skin bridge left

between the two. Both fractures must be reduced and held with clamps before

either is permanently fixed; this ensures that both fractures are reduced

anatomically and that the reductions are maintained. After the temporary

reductions are secured, the less comminuted fracture (usually the ulna) is

fixed with a compression plate and screws; the more comminuted fracture is

fixed subsequently using the same technique.

A number of difficulties may be

encountered during the surgical procedure. Extensive comminution may make it

difficult to restore the bones to their proper length. In this situation, the

interosseous membrane is identified, proximally and distally, and used as a

guide in restoring the bones to an adequate length. Recreation of the

anatomic bow of the radius is critical, and loss of the normal geometry will

lead to permanent loss of forearm rotation. In wound closure, the fascia is

left open and only the skin is closed, because tight fascial closure combined

with postoperative swelling may produce a compartment syndrome.

Long-term problems associated with

fractures of both forearm bones include nonunion, infection, limited motion,

and synostosis between the radius and the ulna. Synostosis is rare and is

usually associated with comminuted fractures at the same level in the forearm

that result from crushing forces. Operative fixation through one exposure is

another well-documented cause of synostosis. Nonunion can occur from inadequate

fixation (e.g., using plates of insufficient strength or

of improper length). One must ensure that six cortices of fixation on each side

of the fracture are achieved, and 1/3 tubular plates (although

easy to contour) are never appropriate for operative fixation of forearm

fractures. Nonunion also occurs with closed reduction and plaster cast

immobilization, and in the adult population fractures of both forearm bones are

an absolute indication for ORIF.