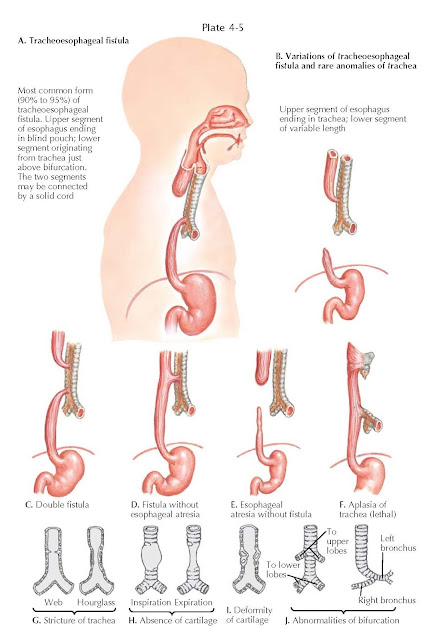

Tracheoesophageal

Fistulas and Tracheal Anomalies

Tracheoesophageal fistula (TOF) and esophageal atresia rarely occur as

separate entities, but they are often seen in various combinations: esophageal

atresia with upper fistula, lower fistula, and double fistulas. Approximately 10%

of infants with esophageal atresia do not have a fistula, but there is a long

gap between the esophageal segments. An isolated tracheoesophageal fistula (H or

N fistula) can occur without an esophageal atresia. The cause of these

congenital anomalies is not well understood. Esophageal atresia is usually

sporadic and rarely familial.

Maternal polyhydramnios and a small

or absent fetal stomach bubble on antenatal ultrasonography suggest the

possibility of esophageal atresia antenatally. Postnatally, the diagnosis can

be suspected in a newborn infant who has excessive mucus and cannot handle his

or her secretions adequately. Suction provides temporary relief, but the

secretions continue to accumulate and overflow, resulting in aspiration and respiratory

distress. Feeds are also regurgitated and aspirated. The TOF provides a

low-resistance pathway for respiratory gases and gastric distension, and

subsequent rupture may further compromise ventilation.

Formerly, the diagnosis was made by

using a contrast study with barium or Gastrografin (meglumine diatrizoate);

however, there is the danger of aspirating these materials into the lungs. The

diagnosis can readily be made by passing a fairly large radiopaque plastic catheter

through the nose or mouth into the pouch. When the catheter cannot be advanced

into the stomach, the catheter should then be taped in place and put on constant

gentle suction. This keeps the pouch free of saliva and minimizes the chances

of aspiration pneumonitis. On the chest radiograph, it will be noted that the

tip of the catheter is usually opposite T2-T3. If the surgeon prefers a

contrast study, no more than 0.5 mL of contrast material should be introduced

through the catheter, with the child in the upright position. Radiography will

show the typical esophageal obstruction, and the contrast material should then

be immediately aspirated.

Initial management is aimed at

keeping the airway free of secretions using a 10-Fr double lumen Replogle tube

in the proximal pouch on continuous low pressure suction. The ideal surgical

procedure consists of disruption of the fistula and an end-to-end anastomosis of

the esophagus. If there is a long gap between the esophageal segments, surgery

is delayed to allow the pouches to elongate and hypertrophy over a period of up

to 3 months. During this time, the infant is fed through a gastrostomy, and the

upper pouch is kept clear of secretions.

Anomalies and Strictures of The Trachea

Tracheal anomalies are very rare.

With stricture of the trachea, there is local obstruction of the passage of

air. In the absence of cartilage, the trachea can collapse and therefore

obstruct on expiration. With deformity of cartilage, there is obstruction on

inspiration and expiration. When abnormal bifurcations are

present, the right upper or left upper lobe bronchi (or both) arise

independently from the trachea.

Clinically, stenosis may be

localized or diffuse. The localized form is caused by a web of the respiratory

mucosa or by excessive growth of tracheal cartilage. The diffuse form is caused

by a congenital absence of elastic fibrous tissue between the cartilage and its

rings in the trachea or by an absence of cartilage. Clinically, obstruction

of the trachea causes chronic dyspnea; cyanosis, especially on exercise; and

repeated attacks of respiratory tract infection. The diagnosis is established

by bronchoscopy and by radiography.

For localized obstruction, surgery

is advisable, either dilatation or excision with end-to-end anastomosis.

Resection and anastomosis of the trachea can be carried out, including up to

six tracheal rings. For generalized stenosis, only supportive therapy is available.