ACUTE INTERSTITIAL

NEPHRITIS

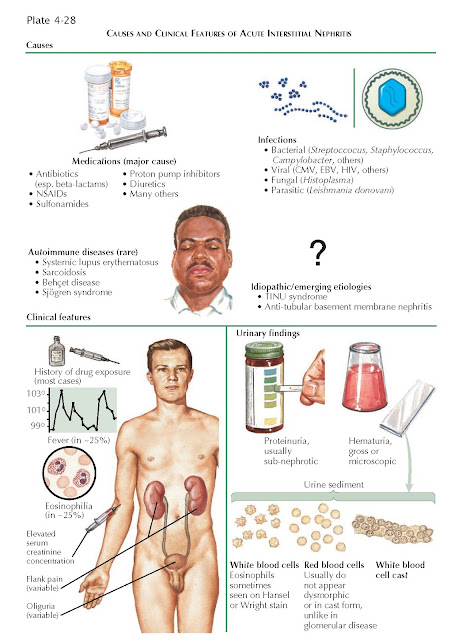

Acute interstitial nephritis (AIN) is a major

cause of intrarenal acute kidney injury (AKI) and features diffuse inflammation

and edema of the tubulointerstitium. It accounts for a small fraction of AKI in

general but is seen in up to 25% of patients with AKI who undergo a renal

biopsy, generally after more common causes (such as prerenal state and acute

tubular necrosis) have been excluded.

PATHOPHYSIOLOGY

The major known causes of AIN fall

into three broad categories: drugs, infectious diseases, and autoimmune

disorders. Since the implicated drugs and infectious pathogens only cause AIN

in a small fraction of patients, the host’s immune response is likely critical

to the disease pathogenesis.

Drug reactions account for over two

thirds of AIN cases. Although associations with many different drugs have been

reported, the most frequent culprits include β-lactam

antibiotics, rifampin, sulfonamides, diuretics, proton pump inhibitors, and

nonsteroidal anti-inflammatory drugs. In the past, the major cause of

drug-induced AIN was methicillin, which caused disease in up to one in five

patients, but this antibiotic is no longer used in the United States.

Nonetheless, the incidence of drug-induced AIN is rising overall because of

increasing drug use, especially in the older population.

Many drugs cause disease by

inciting a hypersensitivity-type reaction. β-lactams, for example, can serve as haptens by

attaching to proteins on the tubular basement membrane, and forming an antigen

that triggers a T-cell response. NSAIDs, however, appear to trigger disease

through a largely nonallergic mechanism. Although the exact mechanism is

unknown, it has been hypothesized that selective suppression of renal

cyclooxygenase enzymes leads to increased metabolism of arachidonic acids

toward leukotrienes, which trigger an immune response. NSAIDs may also

infrequently induce a hypersensitivity-type response.

Infections account for 15% of AIN

cases, and responsible agents can include bacteria (e.g., Campylobacter,

Salmonella, Streptococcus, Staphylococcus, Escherichia

coli, Brucella), viruses (e.g., cytomegalovirus, Epstein-Barr virus,

HIV, herpes simplex virus), fungi (e.g., Histoplasma), and parasites

(e.g., Leishmania donovani). Such agents can induce inflammation either

through direct invasion of the renal parenchyma or through activation of the

immune system in remote organs with collateral tubulointerstitial involvement.

Infectious agents remain an important cause of AIN in developing nations.

Autoimmune diseases account for 10%

of AIN cases, and responsible diseases include systemic lupus erythematosus,

sarcoidosis, Behçet disease, and Sjögren syndrome.

The remaining AIN cases are

considered idiopathic; however, antitubular basement membrane (TBM) nephritis

and tubulointerstitial nephritis/uveitis (TINU) syndrome are now recognized as

two causes of previously “idiopathic” AIN. Anti-TBM nephritis usually occurs in

early childhood and results from circulating anti-TBM antibodies that target

the proximal tubular basement membrane. TINU syndrome was first described in the

1970s, and a small number of cases has been reported since that time. The

athogenesis is unknown but likely immune-mediated.

PRESENTATION AND DIAGNOSIS

Acute interstitial nephritis

typically manifests as AKI following the recent introduction of a new

medication. Eighty percent of patients develop symptoms within 3 weeks of drug

introduction, although there can be a latent period of several months following

onset of NSAID use. The AKI can manifest either as oliguria or as an

asymptomatic elevation in serum creatinine con-centration noted on routine

serum chemistries. In classic descriptions, the renal injury is

accompanied by the triad of fever, rash, and eosinophilia; however, this

picture emerged when the major pathogenetic agent was methicillin, which often

triggered a hypersensitivity-type reaction. At present, largely because of the

growing incidence of NSAID-related AIN, allergic symptoms are less consistent.

Fever, rash, and eosinophilia are each seen in about 15% to 25% of patients,

and the entire triad is seen in only 10%. In addition to these variable

allergic symptoms, a fraction of patients may experience flank pain,

gross hematuria, or both. Flank pain likely represents distention of the renal

capsule secondary to interstitial edema. Hypertension and gross edema are

uncommon.

Urinalysis often reveals proteinuria,

which is mild on quantitative analysis (i.e., <2

g/day) and reflects impaired tubular reabsorption of filtered proteins.

Nephrotic-range proteinuria may rarely be seen in those cases where NSAID

exposure causes both AIN and minimal change disease (see Plate 4-8).

Microscopic analysis of urine often reveals white blood cells (WBCs), red blood

cells (RBCs), and WBC casts. These findings can facilitate the distinction from

acute tubular necrosis (ATN, see Plate 4-3), which is the most common cause of

intrarenal AKI and typically features a bland sediment or epithelial cell

casts. In addition, the lack of RBC casts or dysmorphic RBCs facilitates the

distinction from acute glomerulonephritis. Finally, the presence of proteinuria

and an active sediment can be used to exclude prerenal state, which may also

occur in the setting of NSAID use secondary to interfe ence with

tubuloglomerular feedback (see Plate 3-18).

Eosinophiluria (defined as

eosinophils >1% of WBCs seen in urine) occurs in some

patients with AIN but can only be detected using special stains, such as Hansel

or Wright stains. Moreover, eosinophiluria may be a non- specific finding because

it can also occur in atheroembolic renal disease, urinary tract infections, and

some glomerulonephritides. Thus its diagnostic utility is unclear.

Renal ultrasound results are often

normal. Diffuse cortical echogenicity secondary to interstitial inflammation has

been described, but no studies have validated the sensitivity or specificity of

this finding. Gallium scan has been proposed as a potentially useful diagnostic

tool. Gallium is a radioactive tracer that colocalizes with WBCs and has

traditionally been used for the detection of abscesses. In acute interstitial

nephritis, there is diffuse, bilateral uptake of gallium, which reflects the

underlying inflammatory process. There are conflicting results, however,

regarding the sensitivity and specificity of this procedure for the diagnosis of

AIN. Thus it is seldom used in clinical practice.

The distinction between AIN or

atheroembolic renal disease can sometimes be challenging because both may cause

AKI with eosinophiluria and mild proteinuria, fevers, arthralgias, and rash.

The rash in AIN, however, is typically maculopapular and erythematous, whereas

atheroembolic disease usually causes livedo reticularis or mottled, violaceous

toes. Atheroembolic disease is also more likely in certain high-risk

populations, such as elderly patients with vascular disease who have recently

undergone an open surgical or percutaneous procedure.

Biopsy is required to confirm the

diagnosis of AIN. It is typically performed in patients with unexplained AKI

and a cellular urine sediment who do not quickly respond to termination of

potentially causative drugs. On light microscopy, AIN features a

lymphocyte-pre-dominant interstitial infiltrate typically accompanied by edema.

The presence of eosinophils suggests a druginduced, allergic cause.

Occasionally, granulomas may also be noted. Tubular injury may occur, with

passage of lymphocytes across the tubular basement membrane (“tubulitis”), but

the glomeruli and blood vessels are typically spared. Inflammation is typically

much more prominent in the renal cortex than in the

medulla.

TREATMENT

Initial treatment for acute

interstitial nephritis includes discontinuation of all potential offending

drugs and eradication of any potential infections. Once an offending drug has

been identified it should never be reintroduced because it will reliably cause

future episodes of interstitial nephritis.

In addition, there is recent

evidence that early steroid administration in drug-induced disease leads to

faster and greater recovery of renal function. Thus, in the absence of any

contraindications, a limited course of corticosteroids may be considered.

PROGNOSIS

Most patients will experience

complete recovery of renal function. A minority will progress to end stage

renal disease and require renal replacement therapy. The duration of renal

failure, rather than the peak serum creatinine concentration, appears to be the

most important indicator of eventual recovery. Some data also suggest patients

of advanced age may have a less favorable prognosis.