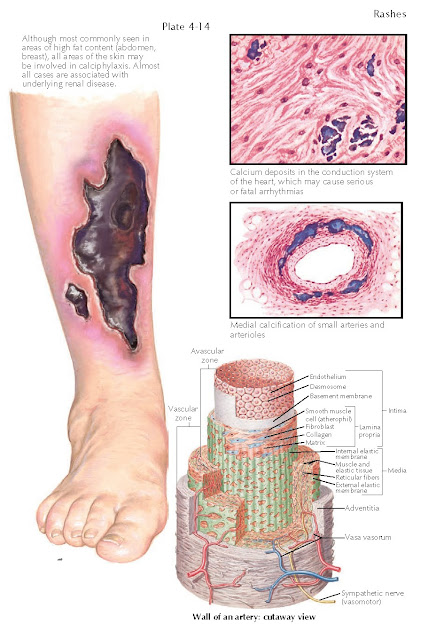

CALCIPHYLAXIS

Calciphylaxis (calcific uremic arteriolopathy) results from deposition of

calcium in the tunica media portion of the small vessel walls in association

with proliferation of the intimal layer of endothelial cells. It is almost

always associated with end-stage renal disease, especially in patients

undergoing chronic dialysis (either peritoneal dialysis or hemodialysis). It

has been reported to occur in up to 5% of patients who have been on dialysis

for longer than 1 year. Calciphylaxis typically manifests as nonhealing skin

ulcers located in adiposerich areas of the trunk and thighs, but the lesions

can occur anywhere. They are believed to be caused by an abnormal ratio of

calcium and phosphorus, which leads to the abnormal deposition within the

tunica media of small blood vessels. This eventually results in thrombosis and

ulceration of the overlying skin. Calciphylaxis has a poor prognosis, and there

are few well-studied therapies.

Clinical Findings: Calciphylaxis is almost exclusively

seen in patients with chronic end-stage renal disease. Most patients have been

on one form of dialysis for at least 1 year by the time of presentation. The

initial presenting sign is that of a tender, dusky red to purple macule that

quickly ulcerates. The ulcerations have a ragged border and a thick black

necrotic eschar. The ulcers tend to increase in size, and new areas appear

before older ulcers have any opportunity to heal. Ulcerations begin proximally

and tend to follow the path of the underlying affected blood vessel. Their most

prominent location is within the adipose-rich areas of the trunk and thighs,

especially the abdomen and mammary regions. Patients often report that

ulcerations form in areas of trauma. The main differential diagnosis is between

an infectious cause and calciphylaxis. Skin biopsies and cultures can be

performed to differentiate the two. Skin biopsies are diagnostic. Radiographs

of the region often show calcification of the small vessels, and this can be

used to support the diagnosis. Patients who develop calciphylaxis have a poor

prognosis, with the mortality rate reaching 80% in some series. For some

unknown reason, those with truncal disease tend to survive longer than those

with distal extremity disease. Complications caused by the chronic severe

ulcerations (e.g., infection, sepsis) are the main cause of mortality.

Laboratory findings

often show an elevated calcium × phosphorus product. A calcium × phosphorus

product greater than 70 mg2/dL2 appears to be an independent risk factor for

development of calciphylaxis. Other risk factors are obesity,

hyperparathyroidism, diabetes, and the use of warfarin. Elevated parathyroid

hormone (PTH) levels are often found in association with calciphylaxis. The

exact role that PTH plays is unknown, but it has been reported that

parathyroidectomy, a standard treatment for calciphylaxis in the past, is not

an effective means of therapy. PTH may play a role in starting the disease, but

it does not appear to be necessary to exacerbate or cause continuation of

calciphylaxis.

Pathogenesis: The exact mechanism of calcification of the

tunica media of blood vessels in calciphylaxis is not completely understood.

The fact that it is seen almost exclusively in patients undergoing chronic

dialysis therapy has led to many theories on its origin. The final mechanism is

a hardening of the vessel wall with calcification and intimal endothelial

proliferation that leads to rapid and successive thrombosis and necrosis.

Histology: The main finding is of calcification of the

medial section of the small blood vessels in and around the area of

involvement. Thrombi within the vessel lumen are often observed. Intimal layer

endo- thelial proliferation is prominent. The abnormal calcification can easily

be seen on hematoxylin and eosin staining.

Treatment: No good therapy exists for calciphylaxis.

Aggressive supportive care and early treatment of superinfections are critical.

Surgical debridement of wounds is necessary to remove necrotic tissue that

provides a portal for infection. Renal transplantation offers some hope for

cure. Treatment with sodium thiosulfate has shown success in some anecdotal

reports, but this is not a universal cure. The newer bisphosphonate medications

have also been used with limited success. Parathyroidectomy may help initially

with the ulcerations, but it does not decrease mortality.