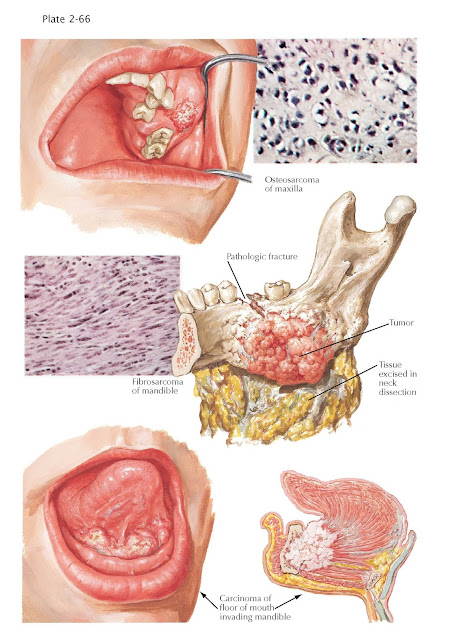

Malignant

Tumors of Jaw

Malignant tumors involving the jawbones are nearly always epidermoid

carcinomas, which are formed from peripheral epithelium and invade the bones

secondarily. Malignant transformation of a benign neoplasm, particularly of a

mixed tumor of salivary tissue, is sometimes seen. Metastases of primary

carcinoma of the thyroid, breast, or prostate to the jaws via the blood-stream

are very rare, and so are malignant primary tumors of odontogenic, osteogenic,

or other origin.

Though osteogenic sarcoma is

the most common and most malignant of bone tumors, only 2% to 3% of cases

appear in the jawbones. Trauma is believed to play a role in its etiology, as

evidenced by clinical histories and experimental production in animals.

It is a solitary growth, which differentiates it from

various tumors of nonosteogenic origin (e.g., endothelioma, multiple myeloma).

The maxillary tumor illustrated has caused wide, mottled destruction of bone,

as revealed by radiographic findings. The classic “sun-ray” pattern seen in the

long bones is seldom appreciated in the jaws, although new bone formation may

be noted. The swelling can involve the entire maxilla and portions of the

palate, with invasion into the antrum. Pain, paresthesia, swelling, tenderness,

and displacement of teeth, with disturbed mastication, are associated symptoms.

Hematologic metastasis can be an early phenomenon.

The histopathologic picture

shows immature cells, which are pleomorphic and hyperchromatic, with some

admixture of stroma, myxomatous tissue, cartilage, and osteoid tissue.

Pathologic descriptions sometimes refer to osteolytic, osteoblastic, and

telangiectatic (vascular) types. The osteoblastic variety tends to grow more

slowly than the vascular type.

Fibrosarcoma may be formed peripherally and invade the

jaws, or centrally from tissues of the tooth, germ or other mesenchymal

enclaves, or connective tissue elements of the nerves and blood vessels. In the

case of rapidly advancing osteolytic lesions, clinical recognition is usually

delayed until loosening of the teeth, encroachment on the antrum or nose, or

perforation of the cortical plate has occurred. No evidence of periosteal

activity is noted, as is sometimes the case with osteosarcoma. Frequently,

proud flesh in the socket of an extracted tooth is the first sign of an

underlying malignancy. In the mandibular tumor chosen for illustration,

pathologic fracture was caused by the widespread destruction of medullary bone.

The tumor mass has perforated the lingual wall of the mandible, with invasion

of soft tissues in the floor of the mouth and neck. Radiographic examination

showed a blurred, diffuse osteolytic area, denoting an invasive rather than an

expansile growth. The microscopic picture reveals spindle-shaped cells, with

anaplasia and varying amounts of intercellular collagenous tissue; in the

rapidly growing forms, a plump cellular shape with frequent mitoses is seen,

but little intercellular material is present.

Carcinoma invading the

mandible is illustrated

in a lesion of the anterior floor of the mouth. The tumor here is a

grade III malignancy, causing early infiltration of cortical bone, with

progress along the haversian canals and destruction of a large portion of

cancellous bone. At the same time, extension occurs through the lymph

channels to involve the submandibular

and cervical nodes, as well as the soft tissues contiguous to the tumor. The

base of the tongue has become fixed and immobile. A fungating tumor mass is

observed in the floor of the mouth, which is secondarily infected and extremely

painful, with a foul exudate and odor.