ALLERGIC CONTACT DERMATITIS

Allergic contact dermatitis is one of the rashes most frequently

encountered in the clinician’s office. It is responsible for a large proportion

of occupationally induced skin disease. Urushiol from the sap of poison ivy,

oak, or sumac plants is the most common cause of allergic contact dermatitis in

the United States. The clinical morphology, the distribution of the rash, and

results from skin patch testing are used to make the diagnosis. Patch testing

is performed when the causative agent is unknown. Nickel has been the most

frequent cause of positive patch testing in the world for years. Urushiol is

not tested clinically, because almost 100% of the population reacts to this

chemical.

|

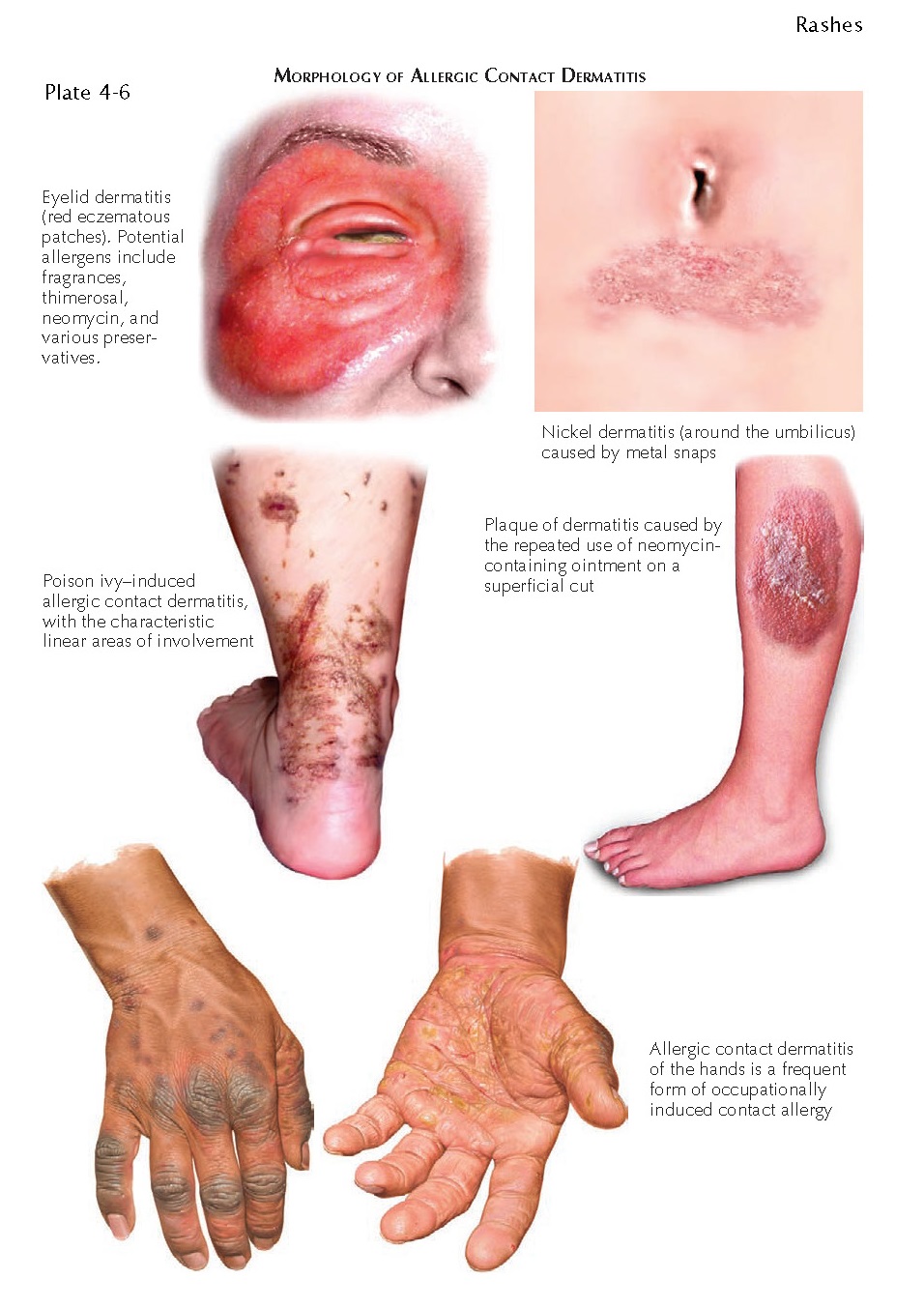

| MORPHOLOGY OF ALLERGIC CONTACT DERMATITIS |

Clinical Findings: Allergic

contact dermatitis can manifest in a multitude of ways. The acute form may show

linear streaks of juicy papules and vesicles. Variable amounts of surrounding

edema can be seen. Edema is much more common in the loose skin around the

eyelids and facial region. Chronic allergic contact dermatitis can manifest

with red-pink patches and plaques with various amounts of lichenification.

There are localized forms and generalized forms. One of the unique forms of

allergic contact dermatitis is the scattered generalized form. Pruritus is an

almost universal finding, and it can be so severe as to cause excoriations and

small ulcerations.

The prototype of allergic contact

dermatitis is the reaction to the poison ivy family of plants. After contact

with this plant, urushiol resin is absorbed into the skin and initiates the

immune system response to cause allergic contact dermatitis. The dose and the

duration of contact with the allergen are important influences on the severity

of the rash that develops. Between 3 and 14 days after exposure, the patient

notices linear juicy papules and vesicles forming at the sites of contact. The

most commonly affected areas are the extremities. Air-borne contact dermatitis

may be seen from burning of wood with the poison ivy vine present. These

reactions are usually seen on skin that was not covered with clothing, and they

can be very severe on the face and eyelids, often causing massive swelling and

impeding vision.

The location of the dermatitis

can be used as a clue to the diagnosis. A nurse with hand dermatitis may be

allergic to a component of the gloves being worn occupationally. A young child

with a lichenified rash around the umbilicus may be allergic to a metal

component of a pant snap or zipper. The most common culprit in these cases is

nickel. Finger dermatitis may be caused by the application of acrylic nails or

nail polish. Allergic contact dermatitis can also be seen within the oral

cavity, most commonly adjacent to dental amalgams or prostheses. Oral allergic

contact dermatitis can mimic oral lichen planus. Lichen planus is usually

widespread and affects the mucosa and gingiva both adjacent to and distant from

any dental restorations.

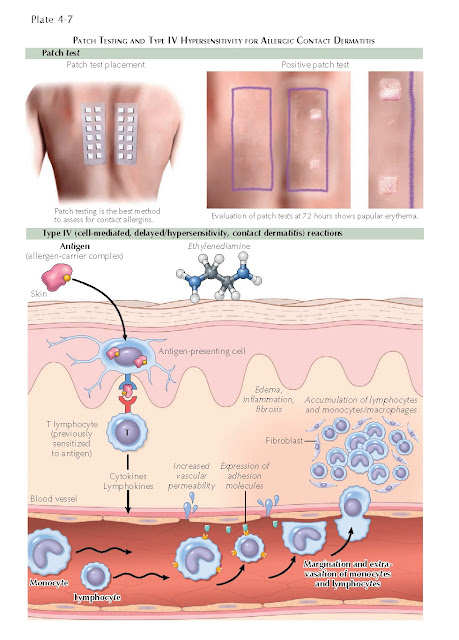

The diagnosis in all these cases

can be made based on patch testing. Chambers loaded with specific

concentrations and amounts of known allergens are applied to the back of the

individual. The patches are left on for 48 hours and then removed. After an

hour, the first reading is made, based on the reaction seen under the chamber.

Elevation of the skin or vesiculation is considered to be a positive reaction.

The presence of only macular

erythema needs to be interpreted cautiously but can be considered a positive

result in certain situations. Pustular reactions are considered to be irritant

reactions and not relevant. The patient must come back for a final reading 3 to

7 days after application of the patches. This is the most critical reading and

gives the most valuable information.

Pathogenesis: Much

is known about the mechanism of allergic contact dermatitis. This form of

dermatitis requires a sensitization and elicitation phase for development.

During the sensitization phase, the patient is exposed for the first time to

the antigen. The antigen is absorbed through the skin and is phagocytosed by an

antigen-presenting cell within the epidermis. The antigen-presenting cell internalizes

the antigen and processes it within its lysosomal apparatus. The processed

antigen is then sent to the cell surface and expressed on a human leukocyte

antigen (HLA) molecule. The antigen-presenting cell migrates to the local

draining lymph node and presents the antigen in association with the HLA

molecule to T cells. The T cells recognize each individual antigen and

proliferate locally, resulting in a clone of lymphocytes that recognize that

specific antigen; these lymphocytes then remain ready for when the patient

comes in contact with the same antigen in the future.

During the elicitation phase, the

patient is reexposed to the antigen. The antigen-presenting cells again process

the antigen and present it to the newly cloned lymphocytes, which migrate back

to the skin and cause the clinical findings of edema, spongiosis, vesicles, and

bullae. If the antigen is exposed in a chronic manner, the findings will be

less acute in nature, and the typical findings of a chronic dermatitis are

seen.

This entire process is dependent

on the size and permeability of the antigen, the recognition and processing of

the antigen by the antigen-presenting cell, and the complex interactions among

multiple T and B cells. Antign-presenting cells and B cells are required for

activation of the T cells and propagation of the allergic contact dermatitis.

Histology: The

initial finding in acute allergic contact dermatitis is spongiosis of the

epidermis with an associated superficial and deep lymphocytic infiltrate with

scattered eosinophils. As the rash progresses, the spongiosis can worsen, and

intraepidermal vesicles start to form. The vesicles may eventually coalesce

into large bullae.

Chronic allergic dermatitis

usually shows acanthosis with spongiosis and eosinophils within the infiltrate.

A superficial and deep perivascular lymphocytic infiltrate is seen.

Excoriations can also be appreciated.

|

| PATCH TESTING AND TYPE IV HYPERSENSITIVITY FOR ALLERGIC CONTACT DERMATITIS |

Treatment: Acute

localized allergic contact dermatitis can be treated with a potent topical

steroid and strict avoidance of the offending agent. Oral sedating

antihistamines work better for the pruritus than their non-sedating

counterparts do. Soaks that help to dry the dermatitis are helpful and include

aluminum acetate (Domeboro’s solution). Because the most common culprit is the

poison ivy plant, time should be taken to explain to the patient the appearance

and nature of this plant. As a good rule of thumb, if a plant has three leaves,

it could be poison ivy: “Leaves of three, let it be.” Allergic contact

dermatitis that is widespread or that affects the eyelids, hands, or groin

region can be treated with a tapering dose of oral corticosteroid over a 2- to

3-week period. If the steroid is tapered too quickly, the patient may

experience a poststeroid flare of their dermatitis, which can be resistant to

further corticosteroid therapy.

Patients who do not respond to

these measures should undergo patch testing to determine whether another

antigen is causing or provoking the dermatitis. Without the use of patch

testing, the allergen will remain unknown and the dermatitis will persist. Not

infrequently, patients are found to be allergic to a fragrance or preservative

that is an ingredient in one of their personal care products. Once they stop

using the product, the dermatitis finally resolves.