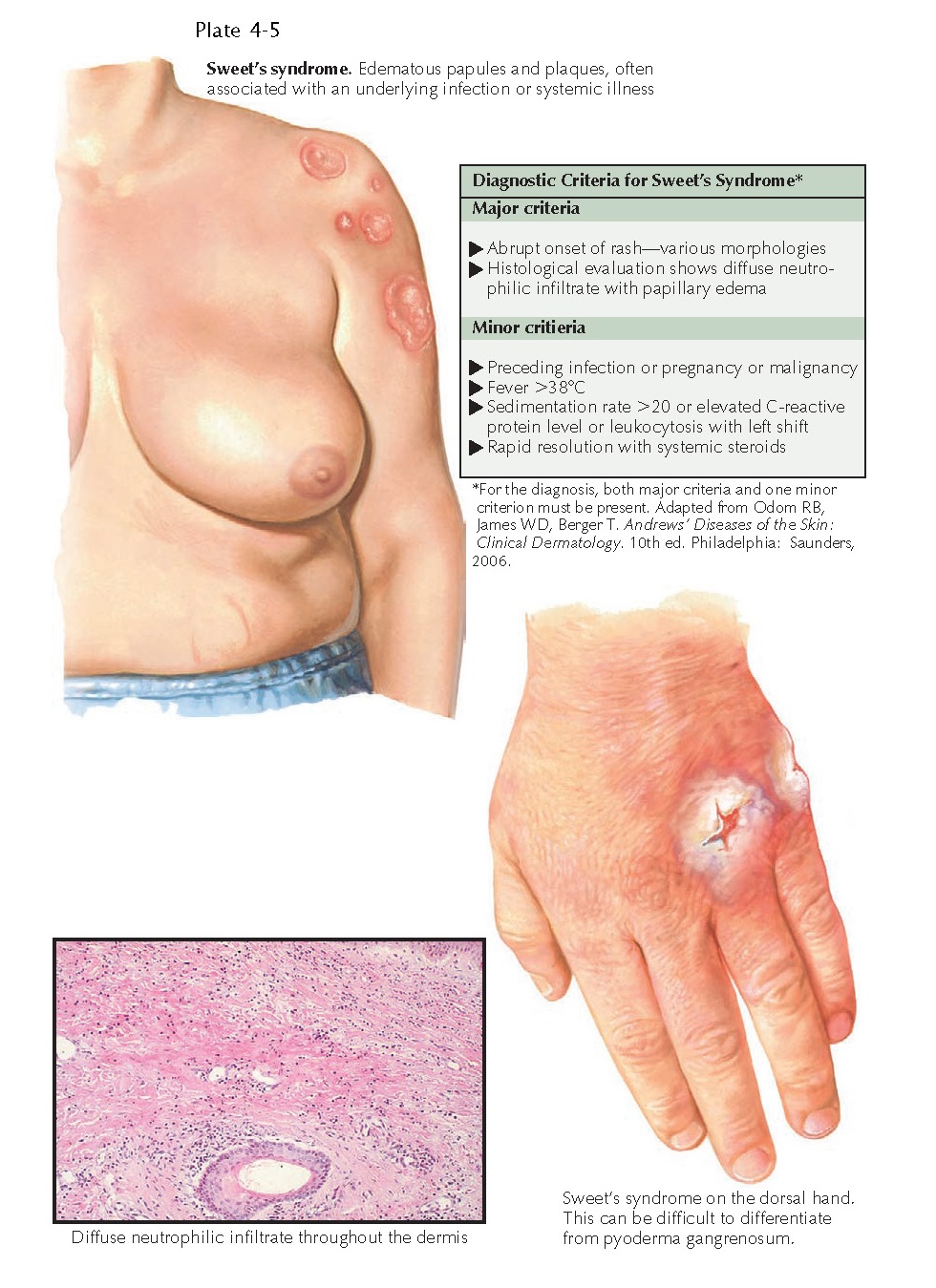

ACUTE FEBRILE NEUTROPHILIC DERMATOSIS

(SWEET’S SYNDROME)

Acute febrile

neutrophilic dermatosis is an uncommon rash that most often is secondary to an

underlying infection or malignancy. The diagnosis is made by fulfilling a

constellation of criteria. Both clinical findings and pathology results are

required to make the diagnosis in a patient with a consistent history.

Clinical Findings: Acute febrile neutrophilic dermatosis is

often associated with a preceding infection. The infection can be located

anywhere but most commonly is in the upper respiratory system. Females appear

to be more likely to be afflicted, and there is no race predilection. Patients

present with fever and the rapid onset of juicy papules and plaques. Because

the papules can look as if they are fluid filled, they are given the

descriptive term juicy papules. They can occur anywhere on the body and

can be mistaken for a varicella infection. Patients also have neutrophilia and

possibly arthritis and arthralgias. If this condition is associated with a

preceding infection, it is usually self-limited and heals without scarring,

unless the papules and plaques are excoriated or ulcerated by scratching.

Variable amounts of pruritus and pain are associated with this skin disease. When

one is evaluating a patient with this condition, a thorough history is

required. A skin biopsy must be performed. A chest radiograph, throat culture,

and urinalysis should be performed to assess for the possibility of bacterial

infection.

Lymphoproliferative malignancies

have also been seen in association with Sweet’s syndrome. The malignancy often

precedes the rash, and the skin disease is believed to be a reaction to the

underlying malignancy. It is important to obtain specimens from these patients

for histological evaluation and culture for aerobic, anaerobic, mycobacterial,

and fungal organisms. The main differential diagnosis is between an infection

and Sweet’s syndrome in cases associated with a malignancy. The most common

malignancy associated with acute febrile neutrophilic dermatosis is acute

myelogenous leukemia. The prognosis in these cases is directly related to the

underlying malignancy. Often, the skin disease continues to recur unless the

malignancy is put into remission.

A few medications have also been

shown to induce Sweet’s syndrome, including granulocyte colonystimulating

factor (G-CSF), lithium, all-trans-retinoic acid, minocycline, and oral

contraceptives.

Pathogenesis: The pathomechanism of Sweet’s syndrome is

theorized to involve the secretion of a neutrophilic chemoattractant factor,

which causes massive amounts of neutrophils to migrate into the skin. The exact

molecule responsible for the recruitment of neutrophils into the skin is

unknown. Reports of exogenous use of G-CSF have led to the theory that it is

responsible for the chemoattraction of neutrophils. Other chemoattractants are

possible players in the pathogenesis, including interleukin-8.

Histology: Histological examination shows massive dermal

edema with a dense infiltrate composed entirely of neutrophils. Varying amounts

of leukocytoclasis are present. Subepidermal bulla formation is possible

because of the extensive dermal edema. Special stains for microorganisms must

be negative to exclude an infectious process, and these must be backed up with

cultures to help disprove an infection, because the histological picture can

mimic an infectious process.

Treatment: Treatment

should be directed at the causative agent. Supportive care is needed for those

with postinfectious Sweet’s syndrome. Topical and oral steroids can

dramatically shorten the course of the disease. Sweet’s syndrome that develops

as a paraneoplastic process secondary to underlying leukemia should be treated

with oral or intravenous steroids once an infectious process has been ruled

out. This can result in a rapid response, but it is short lived once the

steroids are removed. True remission occurs only if the cancer is treated and

put into remission.