Elbow fractures are more

common in children than adults, and treatment can differ greatly from adults

because of the healing and remodeling potential of pediatric fractures. Occult

fractures are also more common in children, in part because not all of the

damaged bone may be ossified. Detecting unossified fractures on plain

radiographs can be difficult, and many of the epiphyses in the elbow region

ossify late. Comparison radiographs of the uninjured elbow often help in

identifying subtle fracture lines and displaced fracture fragments. Any child

who presents with a history of fall or injury, tenderness to palpation about

the elbow, and a fat pad sign on plain radiographs should be treated for an

occult fracture and immobilized in a splint or cast for a minimum of 3 weeks.

New callus formation at the presumed fracture site will typically be present on

plain radiographs at this time to allow the diagnosis to be confirmed.

Supracondylar Fracture Of

Humerus

Supracondylar fractures of the

humerus are the most common elbow fracture in children and are much more common

in children and adolescents than in adults. In children, the fracture typically

involves the thin bone between the coronoid fossa and the olecranon fossa of

the distal humerus, proximal to the epicondyles, and the fracture line angles

from an anterior distal point to a posterior proximal site. In adults,

supracondylar fractures are not usually confined to the extra-articular portion

of the distal humerus, as in children, but extend into the elbow joint.

The most frequent cause of

supracondylar fractures of the humerus is a fall on the outstretched hand with

the elbow extended. By far the most common fracture pattern is an

extension-type injury with posterior displacement of the distal fragment; only

5% to 10% of supracondylar fractures are flexion-type injuries with anterior

displacement of the distal fragment. Extension-type supracondylar fractures are

classified as nondisplaced (type I), partially displaced with the posterior

cortex still intact (type II), and completely displaced with no cortical

contact between the fragments (type III).

In the evaluation of any

fracture, careful assessment of the neurovascular status is important, but this

assessment is even more critical in supracondylar fractures of the elbow

because of the proximity of the brachial artery and median nerve to the distal

spike of the proximal fragment. Neurologic injury or vascular insult and

Volkmann ischemic contracture can result from this type of fracture. A direct

neurovascular injury may occur from the fracture spike, or neurovascular compromise

may occur from severe swelling that accompanies the injury.

Before reduction, the

fractured elbow should be splinted in extension so that arterial circulation is

not compromised by flexion of the distal fragment. When the injury is evaluated

in the emergency department, the neurovascular status of the limb should be

carefully determined and monitored. The first focus of management is on

reduction of the displaced fracture fragments to alleviate any neurovascular

compression if it is present. The supracondylar fracture should be reduced as

soon as possible after injury, preferably with the patient under conscious

sedation or general anesthesia. Closed reduction is carried out by gentle

distraction in the line of the forearm until the humerus is restored to its

full length. The medial or lateral angulation is corrected, and in

extension-type injuries the elbow is flexed greater than 90 degrees for added

stability. With the elbow in extreme flexion, the posterior periosteum and the

aponeurosis of the triceps brachii muscle act as a hinge to maintain the

reduction of the fragments. In more stable fractures (some type II fractures),

this posi- tion may be secure enough with a plaster splint or long-arm cast

alone for 4 to 6 weeks to prevent redisplacement of the fracture fragments and

allow healing.

In assessing the reduction

achieved, displacement in the anteroposterior plane is not nearly as important

as the presence of lateral or medial angulation. If the fracture heals with the

distal fragment tilted medially or laterally, a significant deformity, either

cubitus varus or cubitus valgus, results. Varus or valgus angulation after

reduction is best diagnosed on an anteroposterior

radiograph or a Jones view of the elbow, which reveals a lack of contact

between the two bone fragments on one cortex.

If the adequacy of the

reduction or if the vascular supply of the limb is in question, the fracture

should be treated either with percutaneous pin fixation performed under image

intensification or with open reduction and internal fixation. Type III

fractures and many type II fractures require pin fixation for stability. Image

intensification allows closed reduction of the fracture and percutaneous

insertion of two or three Kirschner wires. Open reduction is usually done

through a lateral approach to the distal humerus. Pins can be passed in a

crossed (medial and lateral pins) or divergent (all lateral pins) pattern, with

care to avoid injury to the ulnar nerve when placing any medial pins. After

internal fixation, the elbow can be splinted in any angle of flexion to avoid

compromising the function of the brachial artery. Vascular exploration and/or

repair is rarely needed but may be indicated if a pulseless, unperfused

extremity does not improve after fracture reduction and operative fixation.

The major long-term

complication of very severe fractures is a change in the carrying angle of the

elbow, primarily cubitus varus, owing to incomplete or loss of reduction at the

time of treatment. The normal carrying angle of the elbow (10 to 20 degrees of

valgus) is decreased or reversed. Despite the abnormal appearance of the elbow,

function is not typically compromised, even with a severe varus deformity.

Closed or open reduction and percutaneous pinning of unstable fractures (types

II and III) are used to prevent varus deformity. Angular malunions that result

in a significant loss of function or cosmetic deformity are best treated with a

corrective osteotomy at the site of the original fracture. The alignment of the

corrective osteotomy is maintained with a plate and screws or an intramedullary

nail. The osteotomy is often supplemented with cancellous bone grafts to ensure

healing. Neurologic injury, although not common, does occur and can involve

either the median, radial, or ulnar nerve, with median nerve injury the most

common. Vascular injury is a devastating complication because it can lead to

Volkmann contracture from a resulting missed compartment syndrome. Regardless

of the reduction and fixation method, care should be taken once the limb is

splinted or placed in a cast to closely monitor it for adequate circulation and

a stable neurologic examination. Distal pulses may not always be easily

palpable owing to vascular spasm from the injury, but if distal perfusion and

capillary refill are normal with no evidence of compartment syndrome then the

limb is likely stable. Finally, all elbow fractures can potentially result in

decreased motion and stiffness.

|

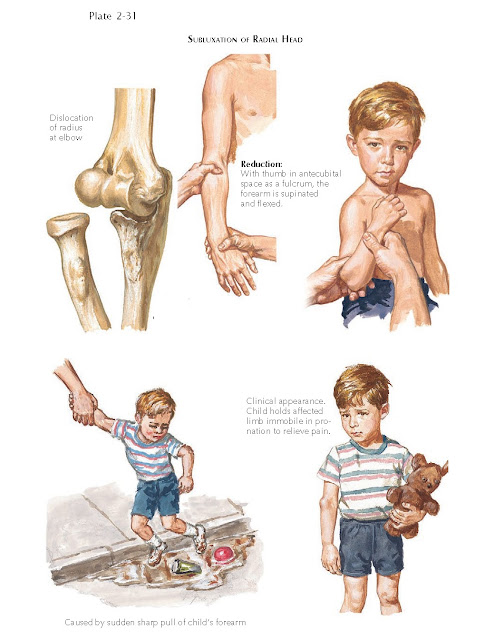

| SUBLUXATION OF RADIAL HEAD |

Fractures Of Lateral

Condyle

A lateral condyle fracture is

the second most common elbow injury in children. Typically, it occurs as an

avulsion injury of the attached extensor muscles. If not reduced well and

securely fixed, this type of fracture tends to lead to significant long-term

problems, includ- ing nonunion, cubitus valgus, and tardy ulnar neuropathy.

Growth arrest of the lateral humerus produces a progressive valgus deformity of

the joint, which, in turn, may lead to ulnar nerve palsy later in life.

Non-displaced fractures of the lateral condyle can be treated with

immobilization in a cast. However, because of a significant risk of late

displacement of the fracture, the patient must be monitored with frequent

radiographic examinations during the first 2 weeks after injury. Displaced

fractures require open reduction and pin or screw fixation to maintain a

satisfactory reduction and avoid the deformity and neurologic complications

asso- ciated with this injury.

Fractures Of Medial

Epicondyle

This injury is the third most

common elbow fracture in children. It results from a valgus stress applied to

the elbow causing an avulsion injury of the medial epicondyle due to

contraction of the flexor-pronator muscles. The fracture is frequently

associated with a posterior or lateral dislocation of the elbow joint.

Dislocation causes the strong ulnar collateral ligament to pull the

epicondyle fragment free from the humerus. During reduction of the dislocation,

the fragment sometimes becomes trapped in the elbow joint. If not incarcerated

in the joint, the fragment may be slightly displaced or rotated more than 1 cm

away from the distal humerus. A significantly displaced fragment is sometimes

easily palpable and freely movable on the medial aspect of the elbow joint.

Nondisplaced and minimally

displaced fractures heal well with splint or cast immobilization. A displaced

fragment trapped in the joint as a result of an elbow dislocation requires open

reduction to restore joint congruity and stability. Significantly displaced

fragments outside the joint may not heal, and some surgeons recommend open

reduction and internal fixation. However, even if the fragment fails to unite,

long-term complications are few.

Fracture Of Radial Head Or

Neck

During a fall on the

outstretched hand, the radial head or neck may fracture as it impacts against

the capitellum, typically from a valgus stress on an extended elbow. Fractures

are usually through the proximal physis and into the radial neck in a Salter II

pattern. Significant angulation of the radial head fragment may occur, and if

the angulation is greater than 30 degrees the fracture should be reduced with

closed manipulation. Reduction is achieved using digital pressure over the

angulated head while alternatively supinating and pronating the forearm.

Although closed reduction is sufficient for most fractures, severely displaced

or angulated fractures of the radial head require percutaneous or open

reduction and internal fixation. Even completely displaced fragments should be

reduced and fixed in place. In a growing child, the radial head should never be

excised, because excision always leads to sig- nificant loss of elbow function.

Dislocation Of Elbow Joint

This childhood injury is less

frequent in younger children but commonly seen in boys between 13 and 15 years

of age and is frequently associated with athletic injuries. Apparent elbow

dislocations in young children or infants should raise concern for a

transphyseal fracture of the distal humerus that is the result of child abuse.

Radiographs of these fractures may be confused for dislocations because of the

lack of ossification of the distal humerus at this age. Most elbow dislocations

in children are posterior, as in adults. Associated avulsion fractures of the

elbow, particularly avulsion fractures of the medial epicondyle, can occur.

With adequate anesthesia, most elbow dislocations can be reduced easily. The

elbow is initially placed in a splint after reduction; and for stable, isolated

injuries, the management is similar to that for adults.

Subluxation Of Radial Head

This injury, also known as

nursemaid elbow, is the most common elbow injury in children younger than 5

years of age and results from longitudinal traction applied to the limb. The

annular ligament moves proximally and becomes interposed between the radius and

ulna, causing the radial head to subluxate. Clinical findings are

characteristic: the injured limb hangs dependent and the child avoids arm use,

the forearm is pronated, and any attempt to flex the elbow or supinate the

forearm produces significant pain. Radiographs do not show any significant bone

abnormality about the elbow. Physical examination almost always reveals

localized tenderness over the radial head. In most patients, reduction can be

achieved by complete supination of the forearm, pressure on the radial head,

and subsequent elbow flexion. Although this causes a moment of fairly severe

pain, supination causes the radial head to slide back into its normal position,

and frequently a “click” is felt as the annular ligament slides back around the

radial neck. Reduction brings almost immediate and complete relief of pain; and

within a few moments, the child begins to use the elbow. If the closed

reduction is successful, immobilization is not necessary. The physician should

explain the cause of the subluxation to the child’s parents and tell them to

avoid longitudinal traction on the limb. The risk of recurrent subluxation is

minimal.