Heart Transplantation: The

Operation

Donor selection

Waiting list mortalit

The appropriateness of using any organ for

transplantation must be balanced against the risk of the recipient dying on the

waiting list if the transplant does not proceed, and in the knowledge that many

other patients who might potentially benefit from transplantation have been

excluded from the list because of donor organ shortage. In the first year on

the waiting list around 60% of patients will receive a heart, while 10–15% will

die waiting.

Suitable hearts

As with all organs, donor sepsis and current

or recent malignancy are contraindications, apart from primary intracranial

malignancy. The heart must be ABO-compatible and lacking HLA anti- gens to

which the recipient has pre-existent antibodies; 30–40% of recipients are

sensitised in this fashion.

Other considerations include the following.

· Donor age: older donors have

an increased burden of coronary artery disease, and donors over 55 years are

seldom used.

· Donor coronary artery disease is associated with early graft failure, unless corrective surgery is

performed to bypass the donor coronary arteries.

· Donor valvular disease or significant left ventricular

hypertrophy. Echocardiography is a

useful way to identify diseased valves (some of which can be repaired) and left

ventricular hypertrophy. A septal thickness of >1.6 cm is a contraindication

to donation.

· Death from carbon monoxide poisoning with carboxyhaemoglobin level above 20%.

· Donor size: aim is to use

hearts from donors with similar weight to recipient; smaller donor hearts and

hearts from females, particularly for recipients with pulmonary hypertension,

tend to fare poorly.

· Left ventricular dysfunction is a common complication of brain stem death, probably related to the

catecholamine storm that occurs. With time and donor fluid management some of

these hearts will recover and be suitable for transplantation; severe dysfunction

(hypokinesia, arrhythmia) is a contraindication.

The donor heart must be macroscopically

examined by the retrieving surgeon. In addition, measurement of cardiac output

and left-side filling pressures, usually with a Swan Ganz catheter is an

essential part of donor assessment.

Transplanting the heart

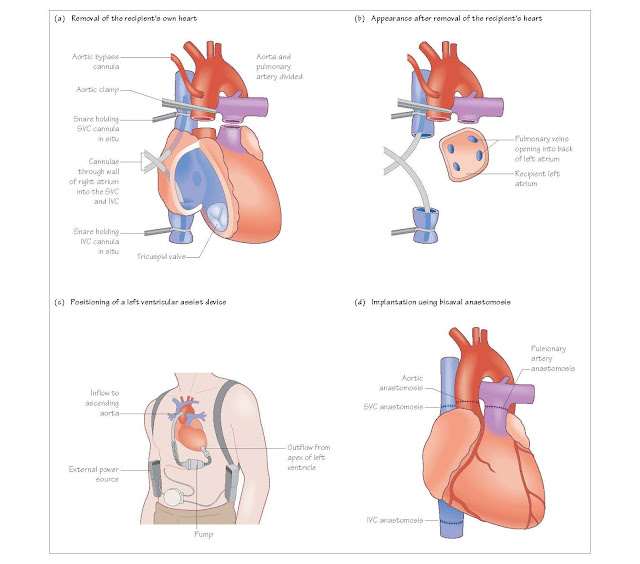

Removing the recipient heart

The heart is approached through a midline

incision dividing the sternum along its length, a median sternotomy. The

recipient is placed on cardiopulmonary bypass so the oxygenation and pump

functions are provided. Cannulae are placed in the ascending aorta and separate

cannulae in the superior and inferior vena cavae.

Blood is then pumped from the vena cavae to

the bypass machine and back into the aortic cannula, and the patient is cooled

to 30°C. When the donor heart is within 20 minutes of the recipient centre the

recipient’s heart is removed. The aorta is cross-clamped and the cavae snared

around the cannulae. The aorta and pulmonary arteries are divided just above

the valves. Both cavae are divided to leave an adequate cuff for sewing to the

donor right atrium. The left atrium is divided along the atrioventricular (AV) groove,

leaving a cuff that contains all the pulmonary veins

Bi-caval implantation technique

The bi-caval implantation technique involves

leaving the donor right atrium intact and instead performing separate

anastomoses with the inferior vena cava (IVC) and superior vena cava (SVC). The

benefits of having a normal size atrium include less atrial dysthyhmia,

pacemaker requirement, tricuspid regurgitation and right ventricular

dysfunction.

Additional considerations

Primary dysfunction of the donor heart is the

cause of most early morbidity and mortality. Ischaemic time is very important.

Mortality increases in a measurable fashion for every hour after the

circulation stops. Good communication is essential between donor and recipient

teams to minimise delays.

Previous cardiac surgery

Patients who have previously undergone a

median sternotomy for cardiac surgery require much longer for cardiectomy, so

it may be necessary to delay the explantation of the donor heart until the

recipient team is ready.

Ventricular assist devices

These are removed at the start of the

recipient procedure, after opening the chest, and may take additional time 2 or

3 hours compared with the 20 minutes it takes to remove a ‘normal’ heart.

Congenital heart disease

The success of neonatal surgery for

congenital heart disease has led to an increasing number of patients coming to

require heart transplantation in later life. Many have unconventional anatomy, clear

delineation of which is essential before surgery. Some procedures, such as in

patients who have had surgery for transposition of the great vessels, may need

cannulation of the femoral vessels instead to facilitate cardiopulmonary

bypass. Additional lengths of aorta and SVC may be needed to cope with

anatomical abnormalities. However, there is no condition, including

dextrocardia, that precludes transplantation.