Endocrine System

Time period: day 24 to birth

Introduction

The glands of the endocrine

system begin to form during the embryonic period and continue to mature during

the foetal period. Functional development can be detected by the presence of

the various hormones in the foetal blood, generally in the second trimester of

pregnancy.

The development of the gonads,

pancreas, kidneys and placenta are covered elsewhere in this book.

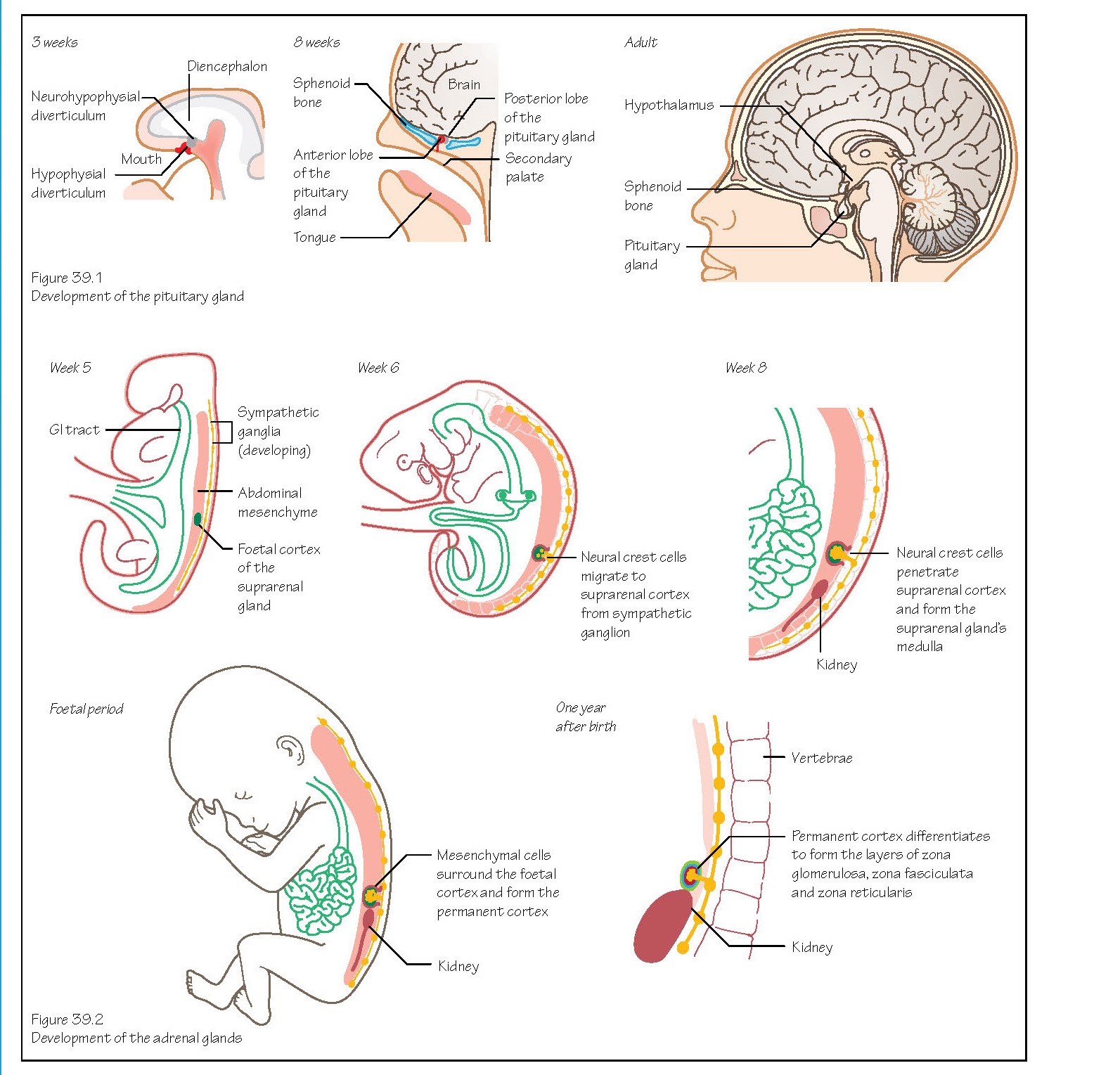

Also known as the hypophysis,

the pituitary gland develops from two sources. An out pocketing of oral

ectoderm appears in week 3 in front of the buccopharyngeal membrane (Figure

39.1). This forms the hypophysial diverticulum (or Rathke’s pouch),

which will become the anterior lobe.

The second source is an extension

of neuroectoderm from the diencephalon, called the neurohypophysial

diverticulum (or infundibulum). The infundibulum grows downwards,

developing into the posterior lobe. These two parts grow towards one another

and by the second month the hypophysial diverticulum is isolated from its

ectodermal origin and lies close to the infundibulum.

Growth hormone secreted by the

pituitary gland can be detected from 10 weeks.

The hypothalamus begins to form

in the walls of the diencephalon (see Chapter 44), with nuclei developing here

that will be involved in endocrine activities and homeostasis.

The pineal body first appears as

a diverticulum in the caudal part of the roof of the diencephalon. It becomes a

solid organ as the cells here proliferate.

The adrenal (or suprarenal)

glands develop from two cell types. The cells of the cortex differentiate

from mesoderm of the posterior abdominal wall near the site of the developing

gonad (Figure 39.2). The adrenaline and noradrenaline secreting cells of the medulla

are derived from migrating neural crest cells that formed a sympathetic

ganglion nearby. These cells become surrounded by the cell mass of the cortex.

The foetal cortex produces a

steroid precursor of oestrogen that is converted to oestrogen by the placenta.

More mesenchymal cells surround the foetal cortex and will become the layers of

the permanent cortex.

The adrenal glands are

exceptionally large in the foetus because of the size of the cortex which

regresses after birth. Substances secreted from the adrenal glands are involved

in the maturation of other systems of the embryo, such as the lungs and

reproductive organs.

This is the first endocrine gland

to develop, beginning at about 24 days between the first and second pharyngeal

pouches from a proliferation of endodermal cells of the gut tube. It begins as

a hollow thickening of the midline where the future tongue will develop. It

eventually becomes solid and then splits into its two lobes.

As the thyroid descends into the

neck it remains connected to the tongue via the thyroglossal duct with

an opening on the tongue called the foramen cecum. The duct degenerates

between weeks 7 and 10 and the thyroid reaches its end location anterior to the

trachea by week 7. If parts of the duct remain the person may also have a pyramidal

lobe. This is quite common and seen in about 50% of the population.

C cells (or parafollicular

cells) are derived from neural crest cells that invade the ultimobranchial

body (a fifth pharyngeal pouch derivative; see Chapter 43).

The inferior parathyroid glands

develop from epithelium (endoderm) of the dorsal wing of the third

pharyngeal pouch. The cells here move with the migration of the thymus

gland into the neck (see Chapter 42). When this connection breaks down they

become located on the dorsal surface of the thyroid gland.

Endoderm cells of the dorsal wing

of the fourth pharyngeal arch begin to collect and differentiate to form

the superior parathyroid glands (initially the superior parathyroid glands are

inferior to the inferior parathyroid glands). These cells are associated with

the developing thyroid gland and migrate with it, but for a shorter distance

than the cells of the inferior parathyroid glands (see Chapter 43). They also

rest on the dorsal surface of the thyroid, but generally more medially and

posteriorly.

Clinical relevance

Pituitary gland

Congenital hypopituitarism is

a decrease in the amount of one or more of the hormones secreted by the

pituitary gland. Symptoms are wide ranging, depending upon which hormones are

affected. The cause is often hypoplasia of the gland or complications with

delivery. Treatment is commonly oral or injection replacement of the

insufficient hormones.

Adrenal glands

Congenital adrenal hyperplasia is an autosomal recessive disease causing excessive production of

steroids, with 95% of patients deficient in the enzyme 21‐hydroxylase (required

in the production of adrenal secretions). There are degrees of severity and

this can cause ambiguous genitalia and infertility. Various treatment options

are available and can include glucocorticoids, sex hormone replacement and

genital reconstructive surgery.

Thyroid gland

Congenital hypothyroidism is

a deficiency in thyroid hormone production. Symptoms include excessive sleeping

and poor feeding. Newborn infants are screened for this and if this deficiency

is found treatment is a daily thyroxine tablet.

Ectopic thyroid tissue left

behind during migration is relatively common but asymptomatic. Parts of the

thyroglossal duct may persist and form a midline, moveable cyst in a child.

Parathyroid glands

Hypoparathyroidism is an

absence of parathyroid hormone. Symptoms are wide ranging but often not

diagnosed until 2 years of age. They include seizures and poor growth.

Treatment includes vitamin D and calcium supplements.

Ectopic parathyroid tissue left

behind during migration is relatively common but asymptomatic more common for the inferior parathyroid glands.