Stomach Anatomy

The stomach is the dilated portion of the

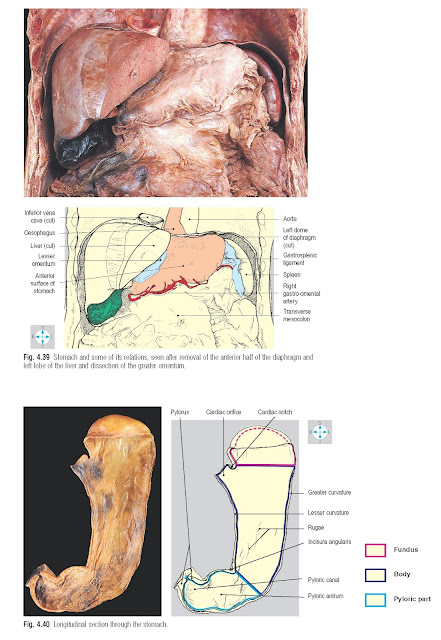

gut, in which the early stages of digestion take place. It lies in the upper

part of the abdomen beneath the left dome of the diaphragm (Fig. 4.39). Proximally, the stomach joins the oesophagus at the cardiac orifice and

distally, it is continuous with the duodenum at the pylorus. Between these two

relatively fixed points, the organ varies considerably in size, shape and

location in response to its muscle tone, the quantity and nature of its

contents and the position of the individual (Figs 4.41 & 4.42). Usually,

the loaded stomach is J-shaped and lies in the left hypochondrium, the

epigastrium and umbilical region of the abdomen.

The oesophagus pierces the diaphragm and has a short

intra-abdominal course before joining the stomach at the cardiac orifice. This

lies a little to the left of the midline at about the level of the eleventh

thoracic vertebra (Fig. 4.42). Anatomical and physiological factors produce a

sphincteric effect at the gastro-oesophageal junction. If this mechanism fails,

gastric contents can regurgitate into the oesophagus (gastro-oesophageal

reflux), causing inflammation of the oesophageal mucosa. The stomach has two

surfaces, anterior and posterior, which meet at two curved borders, the

curvatures (Fig. 4.40). The lesser curvature

extends from the cardiac orifice downwards and to the right, to reach the upper

border of the pylorus. A notch, the incisura angularis, is usually present on

the lesser curvature towards its pyloric end. The greater curvature is longer

and begins at the cardiac notch on the left side of the

cardiac orifice. It arches upwards and to the left before descending along the

left and inferior aspects of the organ to reach the inferior border of the

pylorus.

The pylorus is normally situated just to the right of the

midline at the level of the first lumbar vertebra, on the transpyloric plane.

By convention, the stomach is described as having three

parts, the fundus, the body and the pyloric part (Fig. 4.40). The fundus lies

above an imaginary horizontal plane passing through the cardiac orifice, while

the antrum lies to the right of the incisura angularis. The body lies between

the fundus and the pyloric part and is the largest part of the stomach. In the pyloric part, the

cavity of the pyloric antrum tapers to the right into a narrow passage, the

pyloric canal.

The mucosal lining presents numerous longitudinal folds

or rugae, which are most prominent when the stomach is empty (Fig. 4.40). There

is a well-developed smooth muscle coat, which is thickened around the pyloric

canal and pylorus to form the pyloric sphincter.

Relations

The anterior surface of the stomach lies in contact with

the diaphragm, the anterior abdominal wall and the left and quadrate lobes of

the liver. Posterolateral to the fundus lies the gastric surface of the spleen

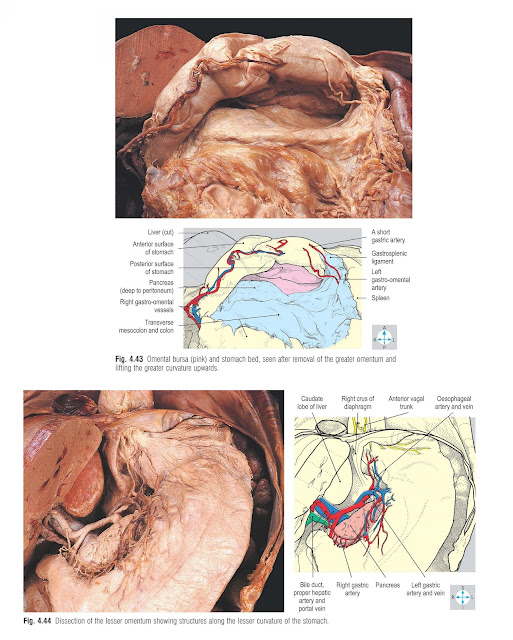

(Fig. 4.39). The remainder of the stomach’s relations are situated posteriorly

and collectively form the stomach bed. This includes the diaphragm, left

suprarenal gland, upper part of the left kidney, the splenic artery, pancreas,

transverse mesocolon and sometimes, the transverse colon (Fig. 4.43). However,

these structures are separated from the stomach by the omental bursa (p. 157).

Gastric ulcers can perforate into either the greater sac or the omental bursa.

Sometimes, ulceration may involve the pancreas or the splenic artery.

Attached to each curvature of the stomach is an omentum,

a double layer of peritoneum. The lesser omentum extends from the liver (Fig.

4.37) to the lesser curvature and also attaches to the abdominal oesophagus and

the commencement of the duodenum (Fig. 4.39). Near the lesser curvature, this

omentum contains the left and right gastric vessels (Fig. 4.44), accompanied by lymphatics and autonomic nerves, while its free border

encloses the portal vein, the bile duct and the proper hepatic artery.

The greater omentum hangs from the distal part of the

greater curvature and from the superior duodenum. Near the greater curvature,

it contains the left and right gastro-omental (gastroepiploic) vessels (Fig. 4.43). To the left, the greater omentum is continuous with the gastro-splenic

ligament, which connects the proximal part of the greater curvature to the

hilum of the spleen.

The stomach is supplied by several arteries, which are

all derived from branches of the coeliac trunk and which anastomose extensively with each other. The coeliac trunk (Fig. 4.45) is a short, wide vessel arising from the anterior aspect of the aorta

just below the diaphragm. It divides into three branches: the left gastric, the

common hepatic and the splenic arteries.

The left gastric artery is the smallest branch, passing

upwards and to the left behind the omental bursa to reach the oesophagus, then

descending along the lesser curvature within the lesser omentum (Fig. 4.44).

Its branches include two or three to the lower oesophagus, which ascend through

the oesophageal opening of the diaphragm. Other branches supply the cardia and

lesser curvature of the stomach.

The common hepatic artery gives rise to the right gastric

and gastroduodenal arteries. The right gastric artery (Fig. 4.44) arises above

the superior duodenum and runs to the left within the lesser omentum, supplying

the lesser curvature and anastomosing with the left gastric artery. One of the

branches of the gastroduodenal artery is the right gastro-omental (gastroepiploic) artery (Fig. 4.43). This vessel runs to the left within the greater

omentum, parallel to the greater curvature, giving numerous branches to the

pyloric part and body of the stomach.

The splenic artery is the largest branch of the coeliac

trunk (Fig. 4.45). It runs a tortuous

course to the left along the superior border of the pancreas, initially behind

the omental bursa and then within the splenorenal ligament, and terminates near

the hilum of the spleen. It provides collateral branches to the pancreas and

terminal branches to the spleen and stomach. There are several gastric

branches, which pass to the greater curvature by way of the gastrosplenic

ligament. Most of these vessels supply the fundus of the stomach and are called

short gastric arteries (Fig. 4.43). However, one branch, the left

gastro-omental (gastroepiploic) artery, continues downwards and to the right

within the greater omentum. It follows the greater curvature, supplies the body

of the stomach and may anastomose with the right gastro-omental

(gastroepiploic) artery.

Fig. 4.45 Stomach and most of the pancreas have been

removed to reveal the coeliac trunk and its branches.

Venous drainage

The veins of the stomach accompany the gastric arteries

and drain into the portal venous system, the portal vein itself receiving the

right and left gastric veins. The splenic vein receives the short gastric and

left gastro-omental (gastroepiploic) veins, while the right gastro-omental vein

usually enters the superior mesenteric vein. The oesophageal tributaries of the

left gastric vein (Fig. 4.44) take part in an important portacaval anastomosis

(p. 185) with tributaries of the azygos venous system within the thorax.

Nerve supply

In the thorax, the vagus nerves form a plexus on the

surface of the oesophagus. From this plexus emerge two principal nerves, the

anterior and posterior vagal trunks, which enter the abdomen on the respective

surfaces of the oesophagus. The anterior vagal trunk (Fig. 4.44), derived

mostly from the left vagus nerve, gives branches to the anterior surface of the

stomach, including the pyloric region. Branches from the posterior trunk, whose

origin is mainly from the right vagus nerve, pass to the posterior surface of

the stomach and also to the coeliac plexus (pp 197, 199). The parasympathetic

innervation of the stomach by the vagus nerves is important in relation to both

secretion and motility of the organ.

Get more articles about sciences, anatomy, physiology, abdomen here