SQUAMOUS CELL

CARCINOMA

Squamous cell carcinoma (SCC) of the skin is the second most common skin

cancer after basal cell carcinoma. Together, these two types of carcinoma are

known as non-melanoma skin cancer. SCC accounts for approximately 20% of all

skin cancers diagnosed in the United States. SCC can come in many variants,

including in situ and invasive types. Bowen’s disease, bowenoid papulosis, and

erythroplasia of Queyrat are all forms of SCC in situ. A unique subtype of SCC

is the keratoacanthoma. Invasive SCC is defined by invasion through the

basement membrane zone into the dermis. SCC has the ability to metastasize; the

most common area of metastasis is the local draining lymph nodes. Most forms of

cutaneous SCC occur in chronically sundamaged skin, and they are often preceded

by the extremely common premalignant actinic keratosis.

|

Genital

Squamous Cell Carcinoma

Clinical Findings: SCC of the skin is most commonly located on the

head and neck region and on the dorsal hands and forearms. These are the areas

that obtain the most ultraviolet sun exposure over a lifetime. This type of

skin cancer is more common in the Caucasian population and in older

individuals. It is more prevalent in the fifth to eighth decades of life. The

incidence of SCC increases with each decade of life. This form of non-melanoma

skin cancer is definitely linked to the amount of sun exposure one has had over

one’s lifetime. Fair-skinned individuals are most commonly affected. There is a

slight male predilection. Other risk factors include arsenic exposure, human

papillomavirus (HPV) infection, psoralen + ultraviolet A light (PUVA) therapy,

chronic scarring, chronic immunosuppression, and radiation exposure. Transplant

recipients who are taking chronic immunosuppressive medications often develop

SCCs. Their skin cancers also tend to occur on the head and neck and on the

arms, but in addition they have a higher percentage of tumors developing on the

trunk and other non–sun-exposed regions.

SCCs of the skin can occur with

various morphologies. They can start as thin patches or plaques. There is

usually a thickened, adherent scale on the surface of the tumor. Variable

amounts of ulceration are seen. As the tumors enlarge, they can take on a

nodular configuration. The nodules are firm and can be deeply seated within the

dermis. Most SCCs are derived from a preexisting actinic keratosis. Patients

often have chronically sun-damaged skin with poikilodermatous changes and

multiple lentigines and actinic keratoses. Approximately 1% of actinic keratoses

per year develop into SCC.

Subungual SCC is a difficult diagnosis

to make without a biopsy. It is often preceded by an HPV infection, and the

area has often been treated for long periods as a wart. HPV is a predisposing

factor, and with time a small percentage of these warts transform into SCC.

This development is usually associated with a subtle change in morphology.

There tends to be more nail destruction and a slow enlargement over time in the

face of standard wart therapy. Prompt biopsy and diagnosis can be critical in

sparing the patient an amputation of the affected digit.

A few chronic dermatoses can

predispose to the development of SCC, including lichen sclerosis et

atrophicus, disseminated and superficial actinic porokeratosis, warts, discoid

lupus, long-standing ulcers, and scars. Many genetic diseases can predispose to

the development of SCC; two of the best recognized ones are epidermodysplasia

verruciformis and xeroderma pigmentosum.

|

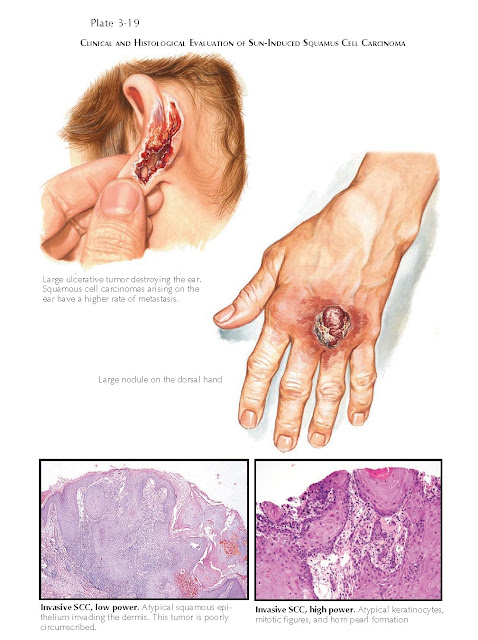

Clinical

And Histological Evaluation Of Sun-Induced Squamus Cell Carcinoma

Pathogenesis: SCC is related to cumulative ultraviolet exposure.

Ultraviolet B (UVB) light appears to be the most important action spectrum in

the development of SCC. UVB is much more potent than ultraviolet A light. UVB

can damage keratinocyte DNA by causing pyrimidine dimers and other DNA

mutations. The damaged DNA leads to errors in translation and transcription and

ultimately can lead to cancer. The p53 gene (TP53) is one of the

most frequently mutated genes. This gene encodes a protein that is important in

cell cycle arrest, which allows for DNA damage repair and apoptosis of those

cells that have been damaged. If the p53 gene is dysfunctional, this

critical cell cycle arrest period is bypassed, and the cell is allowed to

replicate without the normal DNA repair mechanisms acting on the damaged DNA.

This ultimately leads to unregulated cell division and cancer.

Histology: Actinic keratosis shows partial-thickness atypia

of the lower portions of the epidermis. The adnexal structures are spared. SCC

in situ shows full-thickness atypia of the epidermis that also affects the

adnexal epithelium.

SCC is derived from the keratinocytes.

The pathological findings are characterized by full-thickness atypia of the

epidermis and invasion of the abnormal squamous epithelium into the dermis.

Variable numbers of mitoses are seen, as well as invasion into the underlying

subcutaneous tissue. Horn pearls are often seen throughout the tumor. The

tumors are often described as being well, moderately, or poorly differentiated.

Many histological subtypes of SCC have been reported, including clear cell,

spindle cell, verrucous, basosquamous, and adenosquamous cell carcinomas.

Treatment: Actinic keratoses can be treated in myriad ways.

Cryotherapy with liquid nitrogen is very effective and can be used repeatedly.

If this fails to clear the area, or if the actinic keratoses are numerous,

medical therapy is often given with 5-fluorouracil (5-FU) or imiquimod. These

creams work, respectively, by directly killing the affected cells or by causing

the immune system to attack and kill the affected cells. They are both highly

effective. The disadvantage is that they cause an inflamma- tory response that

can be severe and cause erythema, crusting, and weeping during the period of

application, usually 1 month or longer.

The treatment for SCC in situ is often

electrodessication and curettage or simple elliptical excision. 5-FU cream is

also effective but leads to a higher rate of recurrence than the traditional

surgical methods. 5-FU is appropriate as a first-line agent for bowenoid

papulosis. If in follow-up any residual areas are left, surgical removal is

indicated. Occasionally, large areas of SCC in situ on the face are treated by

the Mohs surgical technique.

Invasive SCC should be treated surgically,

with Mohs surgery for lesions on the face or recurrent lesions; standard

elliptical excision is adequate for most invasive SCCs. Some small,

well-differentiated SCCs have been treated successfully with electrodessication

and curettage. The metastatic rate for cutaneous SCC is low, but certain

locations have a higher rate of metastasis. These areas include the lip, the

ear, and areas of chronic scarring or ulceration in which the tumors develop.

Recurrent SCCs, those larger than 2 cm in diameter, and those developing in

patients taking chronic immunosuppressive medications pose a higher risk for

the development of metastatic disease. Patients with chronic lymphocytic

leukemia (CLL) are at much higher risk for metastases; the reason is unknown

but is thought to be related to the immunosuppression resulting from their CLL.

The most common areas for metastasis are the local lymph nodes and lung.

Metastatic SCC of the skin should be

treated with adjunctive radiotherapy and chemotherapy. However, these therapies

have not shown a clear survival benefit, and the key to treatment ultimately

lies in the prevention of metastasis.