Shoulder And Elbow

Injuries

The extreme mobility of the shoulder joint, which

relies on soft tissues – muscles, ligaments and cartilage – for stability,

comes at a price. The shoulder is relatively unstable, and prone to stiffness

if not used. There is a wide range of injury patterns, which change according

to the age of the patient.

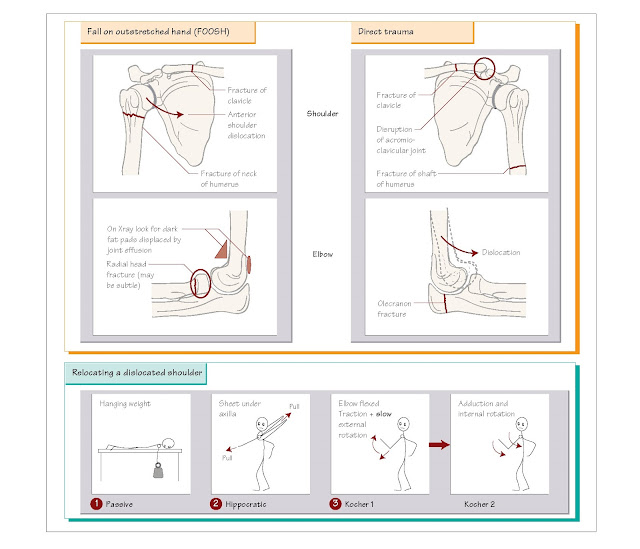

History

In any

injury affecting the upper limb, dominance (handedness) and occupation and

hobbies must be recorded. Shoulder pain can also be referred, e.g. cardiac,

diaphragmatic, respiratory. Injury is usually caused by either a fall onto

outstretched hand (FOOSH) or direct trauma.

Examination

Look Compare with the other

side.

Feel Start at the medial end

of the clavicle and work laterally, feeling for tenderness of clavicle,

coracoid process, acromioclavicular (AC) joint, humeral head and greater

tuberosity. Feel the olecranon, epicondyles and radial head. An elbow effusion

may be felt below the radial head.

Move Limited or painful

shoulder movement warrants an X-ray; very little movement will be possible with

a dislocated shoulder or fracture. A full range of elbow extension makes

fracture unlikely.

Neurovascular examination

Specific

injuries and their corresponding neurovascular deficits are:

• Shoulder dislocation and fracture neck of humerus: test the axillary

nerve – loss of sensation over lower deltoid area.

•

Humeral shaft fractures – radial nerve.

•

Medial epicondyle fracture – ulna nerve injury.

•

Elbow dislocations – brachial artery and median nerve.

Imaging

Plain X-rays

are indicated in most patients presenting with shoulder pain and reduced range

of movement after trauma. Elbow fractures are very unlikely if there is full

elbow extension. Fractures are difficult to see and radiographs should be

examined carefully for evidence of an effusion: the dark shadows caused by the

anterior and posterior fat pads.

Management

Analgesia is

achieved by immobilisation (e.g. sling), and oral analgesics before imaging.

Patients with severe pain and deformity require intravenous opiates and early

assessment. Early active move- ment of the shoulder is important to avoid

stiffness in the elderly.

Ensure

urgent orthopaedic referral for:

•

Any fracture with neurovascular compromise.

•

Open fractures, which require urgent antibiotics.

Common diagnoses

Fractured clavicle

This injury

most commonly occurs at the junction between the middle and outer third. Most

heal with good function by providing rest in a sling and analgesia.

Acromio-clavicular joint injuries

Acromio-clavicular

joint (ACJ) injuries are caused by fall onto tip of shoulder, causing

disruption to the ACJ and ligaments. With complete disruption, the clavicle

will ‘float’ above the acromion. ACJ injuries are treated with analgesia, rest

in a sling and physiotherapy in the first instance, but the more severe grades

of disruption may need fixation later.

Dislocated shoulder

The shoulder

usually dislocates anteriorly (95%) from a fall with the arm in the ‘hailing a

taxi’ position – the humerus is externally rotated and abducted. The humeral

head may be palpable and the patient will support the arm, holding it by their

side.

There are

many different reduction techniques, each with their own proponents. It is

generally best to start with a passive technique that requires only nitrous

oxide/oxygen analgesia and can be conducted by nursing staff. The active

techniques require intravenous analgesia ±

sedation (Chapter 6).

• Passive:

hanging weight technique. The patient lies prone on a couch with the arm

hanging down with a 2–5 kg weight suspended from their wrist.

• Active:

Hippocratic technique. Traction of the patient’s arm, together with mild rotation. The

traditional method of counter-traction involved the doctor’s ‘stockinged foot’

in the patient’s axilla. The modern version uses a sheet under the axilla so an

assistant at the head of the bed can provide counter-traction.

• Active:

modified Kocher’s technique. This technique must not be rushed and requires good

analgesia and sedation.

1. Flex elbow, continuous

gentle traction.

2. Using the forearm as a

lever, the humerus is externally rotated to almost 90° very slowly to

overcome pectoral spasm.

3. The arm is brought

across the body and the humerus internally rotated to achieve reduction.

Reduction

should be confirmed on X-ray, which may show any damage to the humeral head.

Patients with a first dislocated shoulder should have the shoulder immobilised

for 6 weeks to allow the capsule to heal. Patients with multiple dislocations

need surgery to stabilise the shoulder.

Fractured neck of humerus

This injury

is common in the elderly, due to FOOSH; underlying causes for falls should be

sought (Chapter 30). Early mobilisation with appropriate analgesia is necessary

to avoid long-term stiffness (‘frozen shoulder’) that may be far more disabling

than the original injury. Displaced fractures may require reduction ± fixation.

Dislocated elbow

Hyperextension

of the elbow forces the humerus anteriorly over the coronoid process of the

ulna. Neurovascular status should be checked, and this should be reduced by

traction under sedation.

Fractured head of radius

This is the

most common elbow fracture, which can be difficult to see on plain X-ray,

although the elbow effusion ‘fat pad sign’ will be visible. Diagnosis can be

confirmed by tenderness over the radial head, and reduced pronation/supination.

Most fractures make a good recovery with analgesia and early mobilisation.

Fractured shaft of humerus

Twisting

injuries produce spiral fractures, bending injuries transverse fractures.

Radial nerve injury can occur in fractures of the middle third of the humerus.

Diagnoses not to miss

Posterior dislocation of shoulder

This injury

is most common after epileptic fits or electrical injury forcing contraction of

the strong latissimus dorsi muscles. Posterior dislocation is difficult to spot

on X-ray: there is reduced glenohumeral overlap and the greater tuberosity is

not visible, creating the ‘lightbulb sign’: the humeral head appears

symmetrical. If in doubt, ask for an axillary view X-ray.

Scapular fracture

Scapular

fractures can be difficult to see on X-ray, but are usually very painful due to

distension of the tight capsule and may need admission for analgesia.

Significant energy is necessary to fracture a scapula, and other injuries

should be sought.