Odontogenic Infections: Their Spread and Abscess

Formation

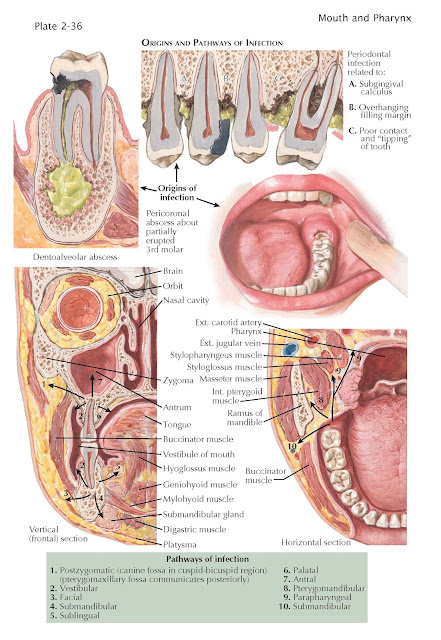

The most frequent causes of inflammatory swellings

of the jaws, the middle and lower thirds of the face, and the upper part of the

neck are infections of the teeth, with the pulp canal or the periodontal

membrane as the primary focus. The dentoalveolar abscess is the most

frequently encountered dental infection. It is usually the end result of dental

caries; more rarely, it originates in a tooth devitalized by trauma. The

abscess may develop very acutely and burrow through bone to lodge under the

periosteum, which it then perforates to induce an intraoral or a facial

abscess. In other instances, a more chronic inflammatory process leads to an

organized granuloma at the root apex, which may remain dormant for years,

evolve slowly into a sterile cyst, or develop into an acute alveolar abscess.

While the abscess is confined to the bone, pain and extreme tenderness of the

involved tooth are the characteristic symptoms. By the pressure of edema, the

tooth is extruded from its socket, so that each contact with the teeth of the

opposing jaw aggravates the pain.

The periodontal abscess is the

second most common odontogenic infection. It arises from an ulcerated

periodontal crevice (pocket), which is created by the loss of attachment (poor

contact) between the tooth on one side and the investing gingiva,

periodontal membrane, and bone on the other. This periodontitis occurs with

increasing severity in older age groups and is the most prominent etiologic

factor in the loss of teeth. Calculous deposits, traumatic occlusion, irritating

filling margins, implanted teeth, and other factors may play a contribut-

ing role. A third odontogenic infection, the pericoronal abscess, originates

in a traumatized or otherwise inflamed flap of gingiva overlying a partly

erupted tooth, usually a lower third molar.

Odontogenic infections involve the

soft tissues chiefly by direct continuity (the numbered pathways are

illustrated in the drawings). Lymphatic spread plays a secondary role, and

hematogenous dissemination rarely results in a facial abscess. Bacteremia, however,

is common and has been demonstrated as a transient phenomenon arising from

chewing or manipulation of apically or periodontally infected teeth. Local

extension follows the line of minimal resistance chosen based on the tooth and

its anatomic proximity to the bone, fascia, and muscle attachment. Where the

muscle layers act as a barrier, extensive cellulitis may spread along the

fascial planes of the head and neck. Infections from the maxillary teeth may

perforate the cortical bone of the palate, the vestibule, or the regions

separated from the mouth by attachments of the muscles of facial expression or

the buccinator muscle. Those from the incisor teeth tend to involve the upper

lip; from the cuspids and premolars, the canine fossa; and from the molar teeth,

the infratemporal space or mucobuccal fold. The vestibular abscess is

generally localized and is not accompanied by excessive edema, owing to the

softness of the tissues and lack of tension. In the advanced stage, a shiny

fluctuant swelling is visible at the region of the root apex or somewhat below

it. Abscess (postzygomatic) of the canine fossa usually bulges into the

buccal sulcus but is chiefly marked by swelling of the infraorbital region of

the face and the lower eyelid. The upper lid, the side of the nose, and the

nasolabial fold and upper lip may be involved by edema.

Infections of the mandibular teeth may

give rise to swellings of the vestibule or the sublingual, submental, or

submandibular space. Abscess of the submandibular region is encountered

with infections of the premolar and molar teeth. The classic sign is a large

visible swell- ing below the mandible, extending to the face and distorting the

lower mandibular border; it is extremely tender and accompanied by trismus. A

submandibular space abscess may easily pass into the sublingual space (5) along

the portion of the gland that perforates the mylohyoid muscle. This results in

elevation of the floor of the mouth and displacement of the tongue to one side.

The submental area may be invaded by passage of pus past the digastric muscle,

resulting in a general swelling of the entire submandibular region. A

dentoalveolar abscess from a lower molar tooth is capable of producing the most

serious and fulminating infections of the submandibular (4), pterygomandibular

(8), and parapharyngeal (9) pathways. A pterygomandibular abscess results in

deep-seated pain and extreme trismus, with some deviation of the jaw owing to

pterygoid muscle infiltration. Infection in this space may, in exceptional

cases, enter the pterygoid and pharyngeal plexuses of veins and result in a

cavernous sinus thrombosis. A parapharyngeal abscess causes bulging of the

pharynx, with equally marked trismus.

The onset of facial cellulitis is

heralded by edema of the soft parts, often quite extensive and without

discernible fluctuation. Pain increases with pressure and induration. As

abscess formation progresses, the central area reveals pitting edema and

eventually becomes shiny, red, and superficially fluctuant. Pain and tenderness

are related to pressure and induration. A fever of 38.5° to 40° C,

leukocytosis, and severe toxemia are characteristic. Trismus occurs when the

elevator muscles are affected by inflammation or reflex spasm caused by pain.

In some cases, rather than the typical production of an abscess, a chronic

cellulitis follows the acute phase, with persistent, deeply attached swelling.

A phlegmon may be apparent from the onset, with a brawny, indurated distention

of muscular and subcutaneous layers, devoid of exudate and showing no

tendency to localize.

Ludwig angina, a purulent inflammation, begins as a phlegmon in

the submandibular space, usually after a molar tooth infection or extraction,

and rapidly spreads to occupy the submandibular region, bounded inferiorly by

the hyoid bone. The floor of the mouth and tongue are raised through

infiltration of extrinsic and intrinsic muscles. The hard, dusky swelling

descends to the larynx, where edema of the glottis, combined with the pressure

of the tongue against the pharynx, interferes with respiration. In addition to

the usual flora of odontogenic infections (alpha, beta, and gamma strep-

tococci and, occasionally, gram-negative bacilli), the bacterial picture in

true phlegmon tends toward anaer- obic organisms, or facultative anaerobes, and

gangreneproducing mixed groups such as the fusospirochetal combination.

Osteomyelitis may produce cellulitis or abscess similar to the

odontogenic variety. Its chief incidence is as a complication following a

traumatic extraction, particularly if performed in the presence of acute

infection, or a comminuted fracture involving the roots of teeth. Occasionally,

it is the result of an abscess contiguous to a large area of bone, and it

typically begins in the lower third molar region. Sclerotic or dense bone is

more easily deprived of nutrition through trauma and at increased risk for

developing an abscess following tooth extraction. Symptoms include those of

cellulitis, with intermittent, deep, boring pain, and sequestrum and involucrum

formation, seen on radiographic imaging in late stages. Symptom and

radiographic resolution results from therapeutic intervention with abscess

drainage and antibiotic therapy.

A fracture of the mandible or

maxilla is always compound where teeth are present, causing the line of

fracture to be contaminated by normal oral flora that seldom produces

infection; however, with projection of a tooth root in the line of fracture,

suppuration typically develops. An externally compounded fracture is more prone

to develop sepsis than a noncomminuted or simple nondisplaced fracture.

Actinomycosis is a specific infection that occurs centrally in

the jaws or peripherally in the soft tissues, where it forms an indurated

swelling with multiple fistulae of the skin, resembling a chronic odontogenic

abscess. Because this is an obligatory oral pathogen, inoculation is usually

through damaged mucosa, most often following oral surgery or recent dental work

and less often following trauma or local radiation therapy. The diagnosis is chiefly

made by a smear of the exudate, which contains peculiar granular yellow bodies (sulfur

granules) and the specific organism (Actinomyces bovis) that causes

the disease. Culture of the organism is unreliable, and biopsy may be required

to establish the diagnosis.