Neurochemical Disorders II: Schizophrenia

Schizophrenia is a syndrome characterized by

specific psychological manifestations, including auditory hallucinations,

delusions, thought disorders and behavioural disturbances. It is a common

disorder with a lifetime prevalence of 1% and an incidence of 2–4 new cases per

year per 10 000 population. It is more common in men and typically presents

early in life. Like all psychiatric disorders there is no diagnostic test for

this condition, which is defined by the existence of key symptoms.

· Positive symptoms:

•

delusions:

abnormal or irrational beliefs, held with great conviction and out of keeping

with an individual’s sociocultural background;

•

hallucinations:

perceptions in the absence of stimuli.

· Negative symptoms:

•

blunting

of mood, apparent apathy, lack of spontaneous speech and action;

•

disordered

speech.

Aetiology

A distinction used to be

made between type 1 and 2 schizophrenia but this has fallen out of fashion as

it may relate more to the length of time that the individual has had the

condition. The cause of schizophrenia is unknown but a number of aetiological

factors have been suggested:

• Genetic

factors: first-degree relatives of people with schizophrenia have a greatly

increased risk of developing the disease; around 10% for siblings, 6% for parents

and 13% for children. Concordance rates in twins are relatively high with

figures varying from 42% to 50% for monozygotic twins and between 0 and 14% for

dizygotic twins. Recent Genome Wide Association Studies (GWAS) have also

confirmed a genetic basis for the condition.

• Environmental

factors: e.g. infections during pregnancy also may have a role, with adoption studies

demonstrating the importance of both genetic and environmental factors. In

these studies gene–environment interactions have been demonstrated in children

of schizophrenic parents adopted into good versus disturbed adoptive

families. In this latter respect one influential theory relating to a family

cause appeals to high levels of ‘expressed emotion’ (hostility, lack of

emotional warmth, over-involvement) as a risk for relapse.

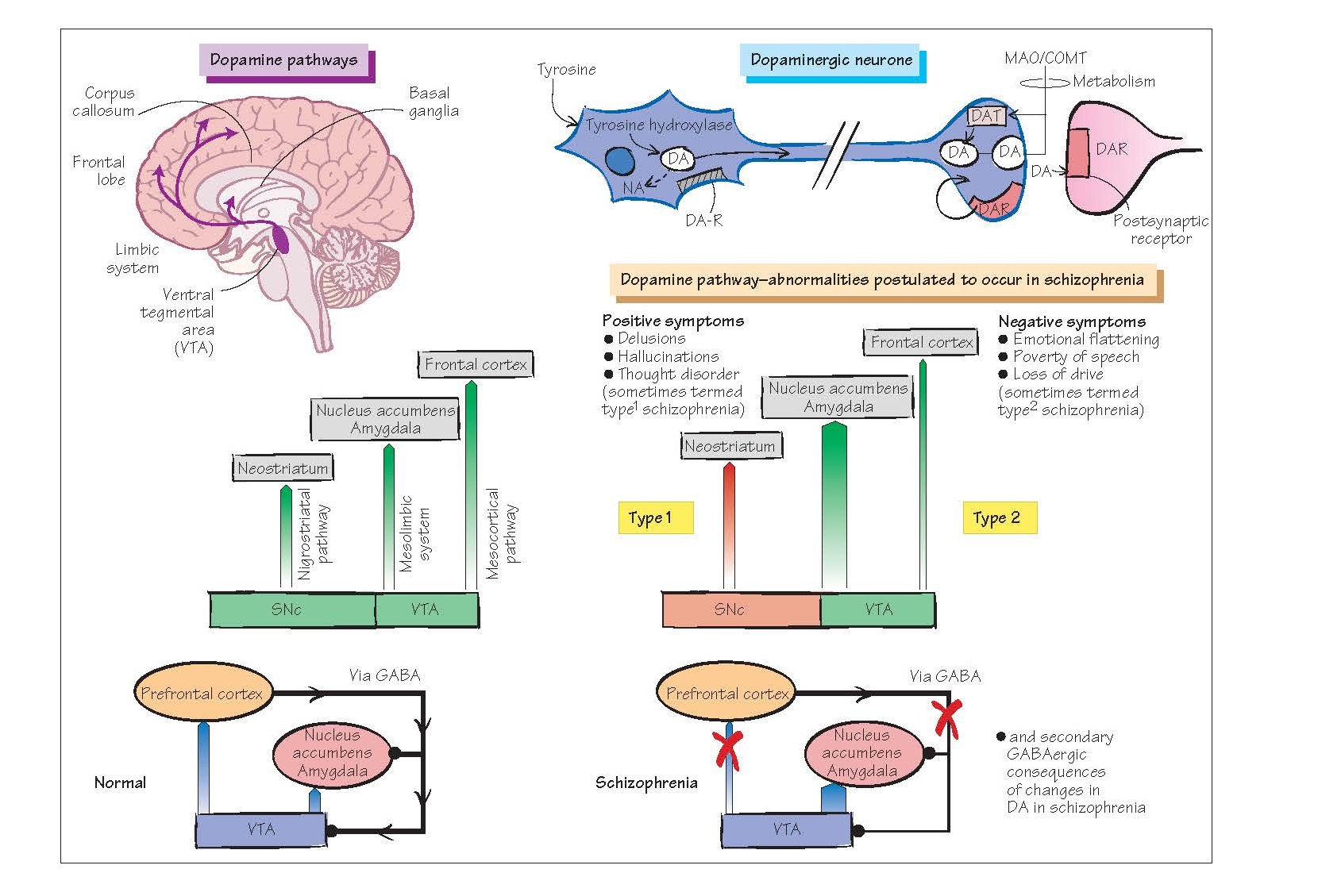

The dopamine

hypothesis of schizophrenia

Basic model

Simply stated, this

embodies the idea that schizophrenia is caused by up-regulation of activity in

the mesolimbic dopamine system. The evidence for this theory comes from:

· Dopamine-blocking drugs show an

antipsychotic effect.

· Drugs that up-regulate dopamine can

produce positive symptoms of psychosis (e.g. amphetamines).

· Some neuroimaging studies in

patients have found evidence of dopamine up-regulation.

The dopamine hypothesis

has been criticized for the lack of direct evidence in its favour and for

certain inconsistencies:

· Dopamine agonists do not produce all

of the symptoms of schizophrenia (notably, they do not produce negative

symptoms);

· Dopamine-blocking drugs do not act

immediately – there may be a long period before symptoms begin to resolve.

Revised model

The above

inconsistencies led to the revision that both dopamine up-regulation and

down-regulation must be invoked to account for the core features of schizophrenia,

with the positive symptoms arising from up-regulation of mesolimbic dopamine

function and the negative symptoms from down-regulation of mesocortical

function.

However, many still

think this as an inadequate explanation of such a complex disorder, and there

is a view that schizophrenia is associated with N-methyl-D-aspartate (NMDA)

(glutamate) receptor hypofunction. This arose from observations

that NMDA blockers such as phencyclidine (‘Angel Dust’) and ketamine (widely

used in anaesthesia) produce a psychotic state (including negative symptoms)

that is held to be more strongly redolent of schizophrenia than the psychosis

produced by dopaminergic agents. There- fore, it has been proposed that

glutamate hypofunction may account for both up-regulation of the mesolimbic

dopamine system, from a diminished excitatory drive of GABAergic inhibition

(i.e. an attenuation of the ‘brake’ system), and down-regulation of the

mesocortical system because of diminished direct drive (the ‘activating’

system).

Cognition in

schizophrenia

Whilst schizophrenia is

traditionally described in terms of psychotic symptoms, there is increasing

evidence of cognitive deficits, particularly in the memory domain,

that may accompany (and perhaps precede) the onset of these symptoms.

Treatment

The mainstay of therapy

in schizophrenia remains the use of drugs that block dopamine receptors, of

which there are at least five subtypes in the brain (D1–D5 receptors; see

Chapter 19). These agents (e.g. chlorpromazine) are called antipsychotics or

neuroleptics. Most neuroleptics block D1 receptors but there is a close

correlation between the clinical dose of antipsychotic drugs and their affinity

for D2 receptors, suggesting that blockade of this receptor subtype may be

particularly important. D2 receptors are found in the limbic system and in the

basal ganglia, and D3 and D4 receptors are found mainly in the limbic areas.

Antipsychotic drugs (eg

chlorpromazine, haloperidol) require several weeks to control the symptoms of

schizophrenia and most patients require maintenance treatment for many years.

Relapses are common even in drug-maintained patients. Unfortunately,

neuroleptics also block dopamine D2 receptors in the basal ganglia, often

producing distressing and disabling movement dis- orders (e.g. parkinsonism,

acute dystonic reactions, akathisia [motor restlessness] and tardive dyskinesia

[orofacial and trunk movements]) which may be irreversible; see Chapter 42).

Blockade of D2 receptors in the pituitary gland causes an increase in prolactin

release and endocrine effects (e.g. gynaecomastia, galactorrhoea; see Chapter

11). Many neuroleptics also block muscarinic receptors (causing dry mouth,

blurred vision, constipation), α-adrenoceptors (postural hypotension) and

histamine H1 receptors (sedation).

Atypical drugs

Some newer drugs have a

reduced tendency to cause movement disorders and are referred to as atypical

agents (e.g. clozapine, risperidone, olanzapine, quetiapine).

With the possible exception of clozapine, these drugs are not more efficacious

than the older antipsychotic drugs. Clozapine is restricted to patients

resistant to other drugs because it causes neutropenia or agranulocytosis in

about 4% of patients. Risperidone and other newer atypical agents are increasingly

used in the treatment of schizophrenia because they are more acceptable to

patients.

It is not clear why some

neuroleptics are ‘atypical’. Clozapine may be atypical because in addition to

being a dopamine D2 antagonist it is a potent blocker of 5-HT2

receptors.