Manifestations of Disease of Tongue

As a consequence of the easy accessibility to clinical inspection, the

tongue, in the course of medical history, has played a rather special role as a

diagnostic indicator of systemic disease. The degree of moisture or dryness of

the lingual mucosa may indicate disturbances of fluid balance. Changes in color

and the appearance of edema, swelling, ulcers, and inflammation or atrophy of

the lingual papillae may represent signs of endocrine, nutritional,

hematologic, metabolic, or hepatic disorders, infectious diseases, or aberrant

ingestions. On the other hand, it should be recognized that the tongue participates with the gingivae and the buccal mucosa in localized pathologic processes

of the oral cavity, and that a number of conditions exist in which the surface

or the parenchyma of the tongue itself is exclusively involved.

Fissured

tongue is a congenital lingual defect, also called a grooved or scrotal

tongue, characterized by deep depressions or furrows, which run primarily in a

longitudinal direction starting near the tip and disappearing gradually at the

posterior third of the dorsum. Both the length and depth of the furrows vary

and can best be demonstrated by stretching the tongue laterally with tongue

blades. It has often been observed that the fissures form a leaflike pattern,

with a median crack larger than the other furrows. In general, the larger

grooves run parallel, with smaller branches directed toward the margin of the

tongue. The mucosal lining of the crevices is smooth and devoid of papillae.

Most often this condition is asymptomatic; rarely, symptoms are reported, which

include mild discomfort when eating spicy or acidic foods or drinks.

Occasionally a fissured tongue is incidentally noted in an individual that also

has macroglossia or a geographic tongue; there is, however; no intrinsic

relationship between these three lingual conditions. Median rhomboid

glossitis is a misnomer, because it is not an inflammatory process but a

developmental lesion resulting from failure of the lateral segments of the

tongue to fuse completely before interposition of the fetal tuberculum impar.

It is an oval or rhomboidal, red, slightly elevated area, about 1 cm in width

and 2 or 3 cm long, contrasting in color with the surrounding parts of the dorsum. This area is devoid of papillae.

Sometimes it may be nodular, mammillated, or fissured. Except for an occasional

secondary inflammation, it causes no subjective symptoms. Visual confirmation

of this benign lesion will differentiate it from a malignant process, thereby

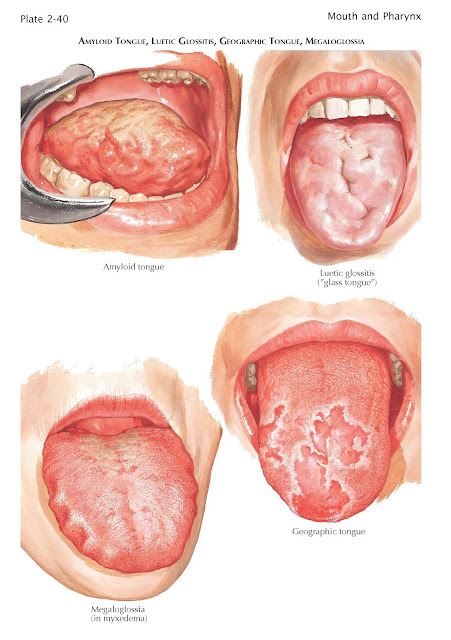

avoiding an unnecessary and costly evaluation. Geographic tongue, otherwise

labeled erythema migrans or Butlin’s wandering rash, is a chronic superficial

desquamation of obscure etiology seen most often in children. It may, however,

recur at intervals throughout life or persist unchanged in degree. The rash is

confined to the dorsum of the tongue and appears, rarely, on the inferior

surface. The dorsal surface is marked with irregular, denuded grayish patches,

from which, at times, the papillae are shed to reveal a dark-red circle of

smooth epithelium bordered by a whitish or yellow periphery of altered

papillae, which have changed from normal color and are about to be shed in

turn. The circles enlarge, intersect, and produce a maplike configuration. The

lesions appear depressed compared with the papillated surface and clearly

demarcated. Continued observation, which reveals the migratory character of the

spots, is necessary to confirm the diagnosis. The geographic tongue may sometimes

be fissured or lobulated at the margin, where it contacts the teeth. Hairy

tongue, or black tongue, is an acquired discoloration. Thick, yellowish,

brownish, or black furry patches, made up of densely matted, hypertrophied

filiform papillae, sometimes cover more than half of the dorsal linguae. The

surface of the tongue is normally coated with a layer of papillae that serve as

taste buds. The tongue also has a protective layer of dead cells known as

keratin. Hairy tongue results because of defective desquamation of the keratin

overlying the papillae. Normally, the amount of keratin produced equals the

amount of keratin that is swallowed with food. The balance is disrupted when

there is an increase in keratin production or a decrease in swallowed keratin.

The keratin or dead cells and the papillae grow and lengthen rather than being

shed, creating hairlike projections that are subjected to entrapment and

staining by food, liquids, tobacco, bacteria, and yeast.

Megaloglossia is, on rare occasions, an isolated congenital

anomaly. An acute form is caused by septic infections and by giant urticaria.

The chronic form is a result of lymphangioma or hemangioma, or a secondary

effect of Down syndrome, acromegaly, or myxedema. (It can also be produced by

tumors, syphilis, and tuberculosis.) In myxedema, the tongue enlarges,

resulting in thick speech and difficulty with mastication and swallowing. The

margins are typically lobulated from the pressure or confinement against the

teeth.

Luetic glossitis has been variously called bald or glazed luetic

tongue, sclerous or interstitial glossitis, or lobulated syphilitic tongue. The

clinical appearance depends on the extent of gummatous destruction, which may

be superficial or deep, causing an endarteritis with a smooth, atrophic

surface. Hyperkeratosis may also be evident. On palpation various degrees of

fibrous induration are detected in the relaxed tongue. The surface is thrown

into ridges, grooves, and lobulations, with a pattern of scars that may assume

a leukoplakic appearance. The induration and scarring are a direct result of

the gummas. The smooth, depapillated, “varnished” surface is, strictly

speaking, an atrophic symptom seen in advanced forms of anemias, vitamin B

deficiency, celiac sprue, Plummer Vinson syndrome, and prolonged cachectic

states.

An amyloid tongue is usually a

part of a generalized amyloidosis. Only occasionally are isolated amyloid

deposits found in the base of the tongue without a generalized disease. The

tongue, as illustrated here, has been heavily infiltrated, together with the

liver, spleen, and other mesodermal organs, in a generalized secondary

amyloidosis resulting from a multiple myeloma. Amyloid deposition causes a

hyaline swelling of connective tissue fibers, with accumulation of waxlike material

and obliteration of vessels through thickening of their walls. Clinically, the

tongue is enlarged and has mottled dark-purple areas with translucent matter.

Furrows and lobules cover the denuded dorsum. The diagnosis is easily

ascertained by a biopsy specimen, which shows the typical brown color when

exposed to Lugol solution and turns blue when sulfuric acid is added. Lugol

solution will also elicit the diagnostic reaction if it is introduced into a

small lingual incision in situ.