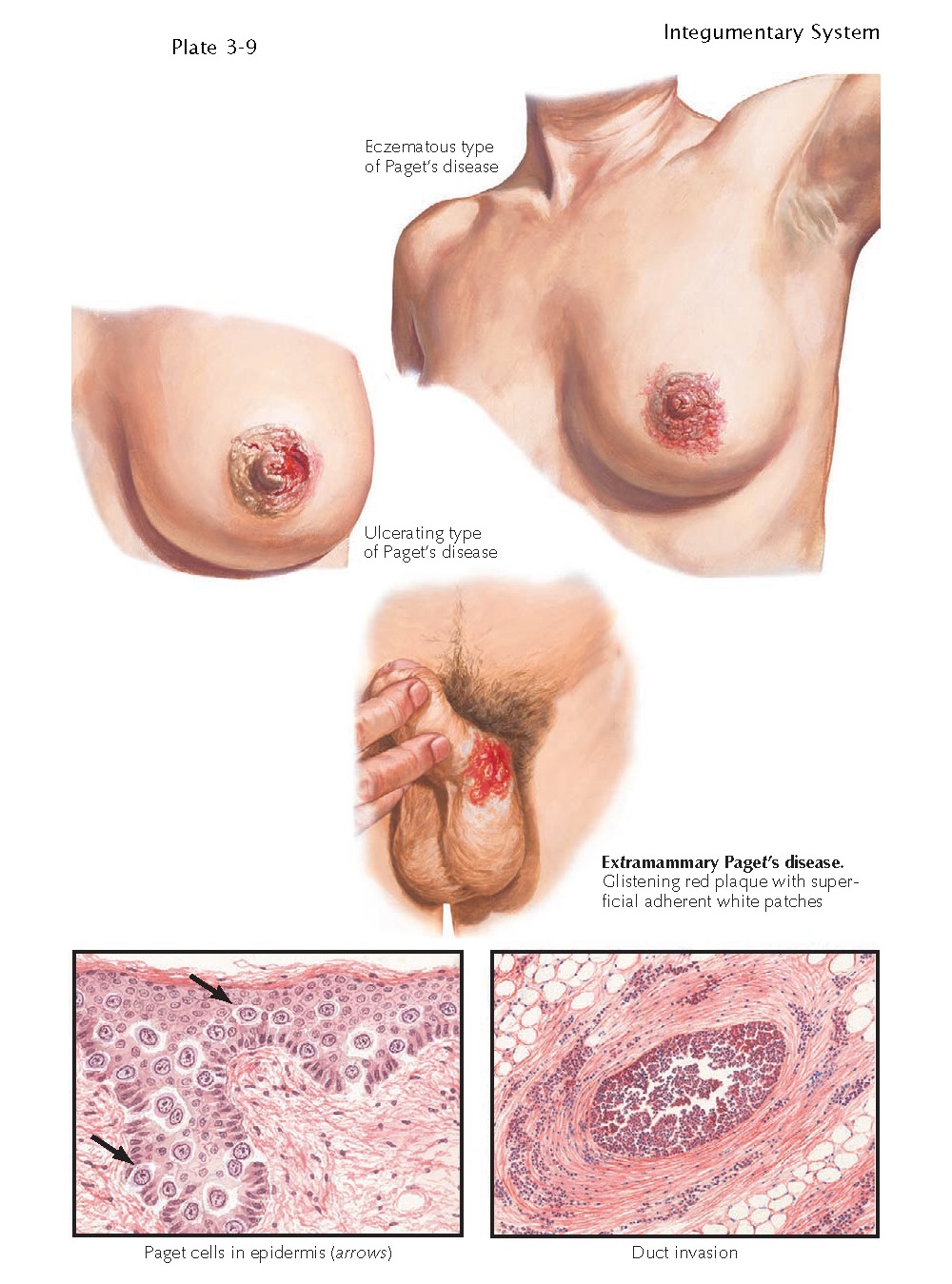

MAMMARY AND

EXTRAMAMMARY PAGET’S DISEASE

Extramammary Paget’s disease is a rare malignant

tumor that typically occurs in areas with a high density of apocrine glands. It

is most commonly an isolated finding but can also be a marker for an underlying

visceral malignancy of the gastrointestinal or genitourinary tract. Paget’s

disease is an intraepidermal adenocarcinoma confined to the breast; it is

commonly associated with an underlying breast malignancy.

Clinical Findings: Extramammary Paget’s disease is most often found

in the groin or axilla. These two areas have the highest density of apocrine

glands. It is believed that extramammary Paget’s disease has an apocrine

origin. There is no race predilection. These tumors most commonly occur in the

fifth to seventh decades of life. Women are more often affected than men. The

diagnosis of this tumor is often delayed because of its eczematous appearance.

It is often misdiagnosed as a fungal infection or a form of dermatitis. Only

after the area has not responded to therapy is the diagnosis considered and

confirmed by skin biopsy.

The tumor is slow growing and is

typically a red-pink patch with a glistening surface. Itching is the most

common complaint, but patients also complain of pain, burning, stinging, and

bleeding. The area is sore to the touch, and there are areas of pinpoint

bleeding with friction. The red, glistening surface often has small white

patches. This has been described as the “strawberries and cream” appearance,

and it is characteristic of extramammary Paget’s disease. As the cancer

progresses, erosions develop within the tumor, and occasionally ulcerations

form. The clinical differential diagnosis is often among Paget’s disease, an

eczematous dermatitis, inverse psoriasis, and a dermatophyte infection. A skin

biopsy is required for any rash in these regions that does not respond to

therapy.

The tumor is often a solitary finding;

however, it can be seen in conjunction with an underlying carcinoma, most commonly

adenocarcinoma of the gastrointestinal or genitourinary tract. Rectal

adenocarcinoma has been the most frequently reported underlying tumor. The

percentage of these tumors that are associated with an underlying malignancy is

not known but is estimated to be low. Appropriate screening tests must be

performed to evaluate for these associations. Usually, the underly- ing tumor

is diagnosed before the extramammary Paget’s disease or at the same time of

diagnosis.

Pathogenesis: The exact mechanism of malignant transformation is

unknown. Two leading theories exist as to the origin of the tumor. The first is

that the tumor represents an intraepidermal adenocarcinoma of apocrine gland

origin. The second theory is that an underlying adenocarcinoma spreads to the

skin and forms an epidermal component that manifests as extramammary Paget’s

disease. Although most believe this tumor to be of apocrine origin, controversy

surrounds this theory, and the exact cell of origin is still unknown. There are

no known predisposing factors.

Histology: The histology is diagnostic of the disease;

however, the pathological appearance often mimics that of melanoma in situ or

squamous cell carcinoma. There are a plethora of pale-staining Paget’s cells

scattered throughout the entire epidermis. This type of pagetoid spread of

cells is often seen in melanoma. The cells can be clustered together and can

have the appearance of forming glandular structures. Immunohistochemical

staining is often used to differentiate melanoma and squamous cell carcinoma

from extramammary Paget’s disease. Extramammary Paget’s disease is unique in

that it stains positively with carcinoembryonic antigen (CEA) and also with

some low-molecular-weight cytokeratins. It does not stain with S100, HMB-45, or

melanin A. The staining pattern with cytokeratins 7 and 20 has been used with

some success to predict an underlying adenocarcinoma; however, the routine use

of these tests is not clinically useful at this time.

Treatment: The prognosis for extramammary Paget’s disease

depends on the stage of the tumor. Disease that is localized to the skin has an

excellent prognosis. The treatment of choice is wide local excision. The risk

of recurrence is high, and lifelong clinical follow-up is required. The

prognosis for disease associated with an underlying adenocarcinoma is dependent

on the stage of the underlying tumor. Lesions associated with an underlying

malignancy have a worse prognosis. Metastatic disease has a poor prognosis, and

various chemotherapeutic reg mens have been tried with and without

radiotherapy.