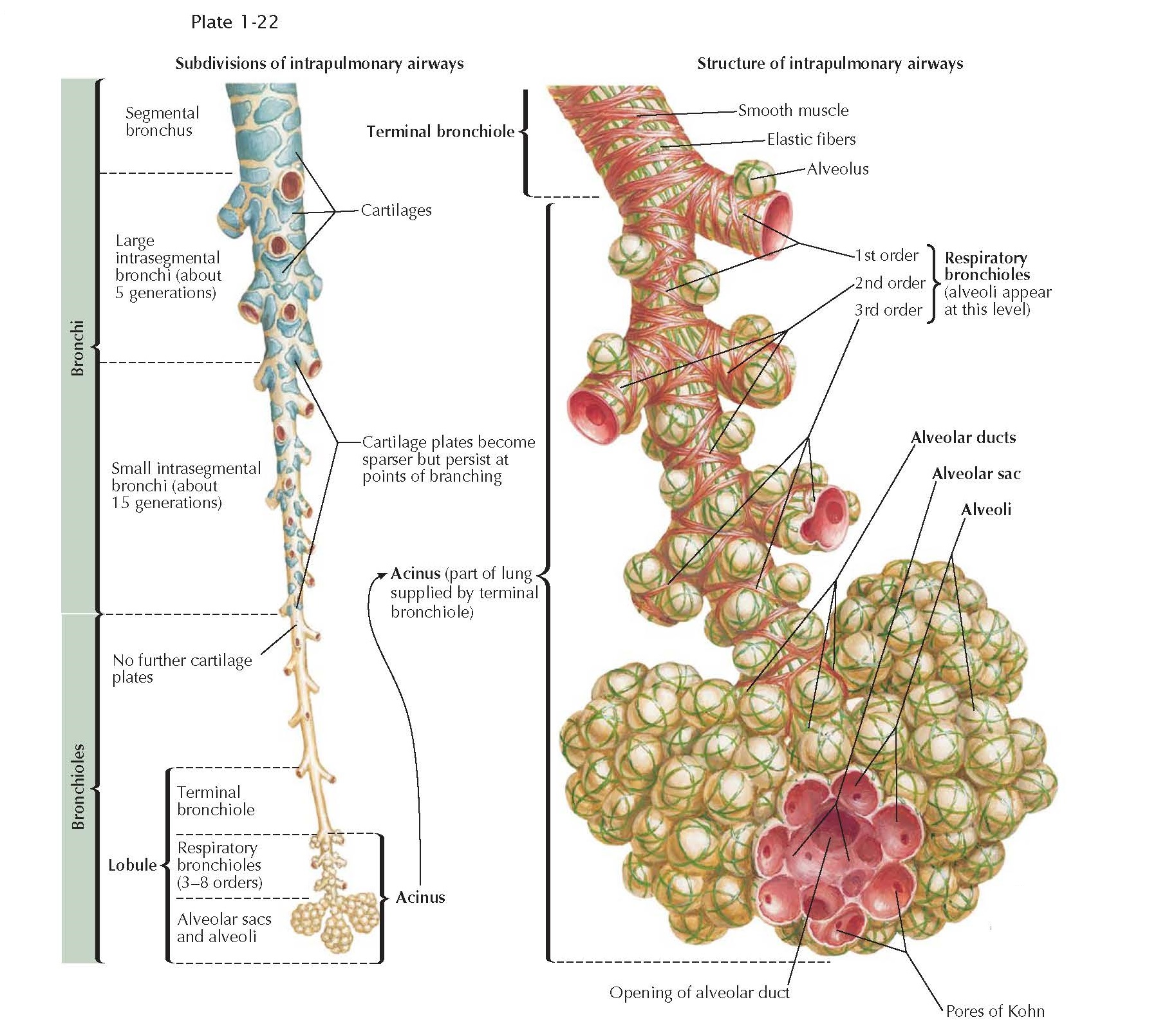

INTRAPULMONARY

AIRWAYS

According

to the distribution of cartilage, airways are divided into bronchi and

bronchioles. Bronchi have cartilage plates as discussed earlier. Bronchioles

are distal to the bronchi beyond the last plate of cartilage and proximal

to the alveolar region. Cartilage plates become sparser toward the periphery of

the lung, and in the last generations of bronchi, plates are found only at the

points of branching. The large bronchi have enough inherent rigidity to sustain

patency even during massive lung collapse; the small bronchi collapse along

with the bronchioles and alveoli. Small and large bronchi have submucosal

mucous glands within their walls.

When any airway is pursued to its

distal limit, the terminal bronchiole is reached. Three to five terminal

bronchioles make up a lobule. The acinus, or respiratory unit, of

the lung is defined as the lung tissue supplied by a terminal bronchiole. Acini

vary in size and shape. In adults, the acinus may be up to 1 cm in diameter.

Within the acinus, three to eight generations of respiratory bronchioles may

be found. Respiratory bronchioles have the structure of bronchioles in part of

their walls but have alveoli opening directly to their lumina as well. Beyond

these lie the alveolar ducts and alveolar sacs before the alveoli proper are

reached.

None of these units is isolated from

its neighbor by complete connective tissue septa. Collateral air passage occurs

between acinus and acinus and between lobule and lobule through the pores of

Kohn in the alveolar wall and through respiratory bronchioles between adjacent

alveoli.

Connective tissue forms a sheath

around airways and blood vessels. It also forms septa that are relatively numerous

in some parts of the edges of the lingula and middle lobe and parts of the

costodiaphragmatic and costovertebral edges. These septa impede collateral

ventilation but do not prevent collateral air drift because they never com

letely isolate one unit from its neighbor in humans.