Heart Anatomy

The heart, enclosed in pericardium,

occupies the middle mediastinum. It is roughly cone-shaped and lies behind the

sternum with its base facing posteriorly and its apex projecting inferiorly,

anteriorly and to the left, producing the cardiac impression in the left lung.

|

| Fig. 2.31 Transverse CT image at the level of the eighth thoracic vertebra. |

|

Fig.

2.32 Borders and valves of the heart and their relationships to the anterior

chest wall.

Borders

It is useful to represent the outline

of the heart as a projection onto the anterior chest wall. When represented in

this way, the heart has right, inferior and left borders (Fig.

2.32). The right border is

formed by the right atrium and runs between the third and sixth right costal

cartilages approximately 3 cm from the midline. The inferior border is formed

mainly by the right atrium and right ventricle. At its left extremity, the

border is completed by that part of the left ventricle which forms the apex of

the heart. The inferior border runs from the sixth right costal cartilage

approximately 3 cm from the midline to the apex, which usually lies behind the

fifth left intercostal space, 6 cm from the midline. In the living, the apex

usually produces an impulse (apex beat) palpable on the anterior chest wall.

The left ventricle together with the left auricle (left atrial appendage) form

the left border of the heart, which slopes upwards and medially from the apex

to the second left intercostal space, approximately 3 cm from the midline.

Most of the anterior surface of the

heart consists of the right atrium and right ventricle (Fig.

2.33). The left ventricle

contributes a narrow strip adjacent to the left border of the heart. The

anterior surface is completed by the right and left auricles. The coronary

sulcus descends more or less vertically on the anterior surface and contains

the right coronary artery embedded in fat. The anterior surfaces of the right

and left ventricles are separated by the anterior interventricular artery (left

anterior descending artery).

Most of the inferior (diaphragmatic)

surface of the heart (Fig. 2.34) consists of the two ventricles, the left usually

contributing the greater area. The posterior interventricular vessels mark the

boundary between these two chambers. The surface is completed by a small

portion of the right atrium adjacent to the termination of the inferior vena

cava.

The posterior surface or base of the heart

(Fig. 2.35) consists mostly of the left atrium together with a small part of

the right atrium.

|

Fig. 2.33 Anterior surface of the heart.

|

Fig. 2.34 Inferior surface of the heart. The inferior part of the

fibrous pericardium has been removed with the diaphragm.

|

Fig.

2.35 The posterior surface of the heart showing the reflection of the serous

pericardium and the site of the oblique pericardial sinus.

Chambers

and valves

The cavities of the right and left

atria are continuous with those of their respective ventricles through the

atrioventricular orifices. Each orifice possesses an atrioventricular valve,

which prevents backflow of blood from the ventricle into the atrium. The

myocardium of the atria is separated from that of the ventricles by connective

tissue, which forms a complete fibrous ring around each atrioventricular

orifice. Interatrial and interventricular septa separate the cavities of the

atria and ventricles. Valves, each with three semilunar cusps, guard the

orifices between the right ventricle and pulmonary trunk (pulmonary valve) and

the left ventricle and ascending aorta (aortic valve). All these valves close

passively in response to differential pressure gradients.

The right atrium receives blood from

the superior and inferior venae cavae and from the coronary sinus and cardiac

veins, which drain the myocardium. The superior vena cava enters the upper part

of the chamber. Adjacent to its termination is a broad triangular

prolongation of the atrium, the auricle (atrial appendage), which overlaps the

ascending aorta (Fig. 2.36).

|

Fig.

2.36 Interior of the right atrium and auricle, exposed by reflection and

excision of part of the anterior atrial wall.

Internally, the anterior wall of

the right atrium possesses a vertical

ridge, the crista terminalis (Fig. 2.36). From the crista, muscular ridges (musculi

pectinati) run to the left and extend into the auricle. The posterior

(septal) wall is relatively smooth but possesses a well-defined ridge

surrounding a shallow depression named the fossa ovalis. This fossa is the site

of the foramen ovale, which, in the fetus, allows blood to pass directly from

the right to the left atrium. The coronary sinus empties into the chamber close

to the atrioventricular orifice. Inferiorly, the right atrium receives the

inferior vena cava immediately after the vessel has pierced the central tendon

of the diaphragm. A fold called the valve of the inferior vena cava (Fig.

2.36) projects into the

chamber and is the remnant of a fetal structure that directed the flow of blood

across the right atrium towards the foramen ovale.

From the right atrium, blood flows

into the right ventricle through the right atrioventricular orifice, which is

guarded by the tricuspid valve (Fig. 2.37). The valve possesses three cusps, the bases of which attach to the margins of the atrioventricular

orifice, while their free borders project into the cavity of the right

ventricle (Fig. 2.38), where they are anchored by fibrous strands (chordae tendineae) to the

papillary muscles of the ventricle. During ventricular contraction (systole),

the papillary muscles pull on the chordae, preventing eversion of the valve

cusps and reflux of blood into the atrium. The valve lies in the midline behind

the lower part of the body of the sternum (Fig. 2.32) and its sounds are heard

best by auscultation over the xiphisternum.

|

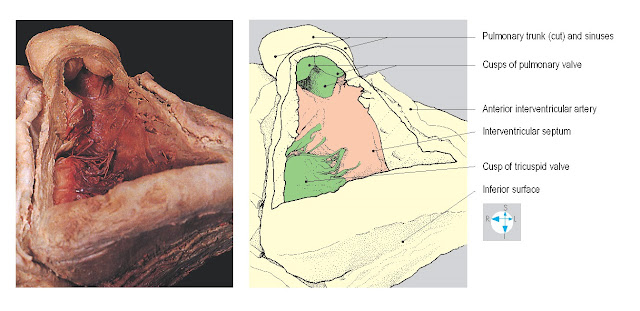

Fig.

2.37 Tricuspid valve, revealed after removal of the lateral wall of the right

atrium.

|

Fig. 2.38 Interior of the right ventricle seen after removal of its

anterior wall.

|

Right ventricle

The right ventricle has the right

atrium on its right and the left ventricle both behind and to its left. The

chamber forms parts of the anterior and inferior surfaces of the heart and

narrows superiorly at the infundibulum, which leads into the pulmonary trunk (Fig.

2.38). The walls of the

right ventricle are thicker than those of the

right atrium and internally possess numerous muscular ridges called trabeculae

carneae (Fig. 2.43). One of these, the moderator band (Fig. 2.54), often

bridges the cavity of the chamber, connecting the interventricular septum to

the anterior ventricular wall. When present, it carries the right branch of the

atrioventricular bundle of conducting tissue (p. 56). Projecting from the

ventricular walls into the interior of the chamber are processes of myocardium,

the papillary muscles, each attached at its apex to several chordae tendineae.

The right ventricle is separated from the left ventricle by the

interventricular septum, which is muscular inferiorly and membranous superiorly

(Figs 2.43 & 2.46).

Pulmonary valve

The pulmonary orifice lies between the

infundibulum and the pulmonary trunk and is guarded by the pulmonary valve (Figs

2.39 & 2.40), which

consists of three semilunar cusps. The valve closes during ventricular

relaxation (diastole), preventing backflow of blood from the pulmonary trunk

into the right ventricle. The valve lies behind the left border of the sternum

at the level of the third costal cartilage (Fig. 2.32). Sounds generated by

this valve are loudest over the anterior end of the second left intercostal

space.

|

Fig. 2.39 Ventricular surfaces of the cusps of the pulmonary valve

seen after removal of part of the anterior wall of the right ventricle.

|

|

Fig. 2.40 Pulmonary and aortic valves seen from above.

|

Left atrium

The left atrium lies behind the right

atrium and forms the base of the heart. It possesses a hook-like auricle (left

atrial appendage), which projects forwards to the left of the pulmonary trunk

and infundibulum. The chamber receives superior and inferior pulmonary veins

from each lung (Fig. 2.35). The four pulmonary veins, together with the two

venae cavae, are all enclosed in a sleeve of serous pericardium, forming the

superior limit of the oblique pericardial sinus. The left atrium forms the

anterior wall of this sinus, which separates the chamber from the fibrous

pericardium and oesophagus. Most of the inner surface of the left atrium is

smooth (Fig. 2.41), although musculi pectinati are present in the auricle.

Mitral (bicuspid) valve

The left atrium communicates

anteroinferiorly with the left ventricle through the left atrioventricular

orifice, which is guarded by the mitral valve. This valve possesses two cusps,

whose bases attach to the margins of the atrioventricular orifice (Fig.

2.41), while their free

borders and cusps are anchored by chordae tendineae to the papillary muscles

within the left ventricle (Fig. 2.42). The valve prevents reflux during ventricular

contraction. Although it lies in the midline at the level of the fourth costal

cartilages (Fig. 2.32), the sounds of the mitral valve are best heard over the apex

of the heart.

From the left atrioventricular

orifice, the left ventricle extends forwards and to the left as far as the

apex. The thickness of the wall of the chamber is normally three times that of

the right ventricle (Fig. 2.43). Internally, there are prominent trabeculae

carneae and papillary muscles (Fig. 2.46). The chamber narrows as it passes

upwards and to the right behind the infundibulum to form the aortic vestibule (Fig.

2.44), the part of the ventricle

that communicates with the ascending aorta through the aortic orifice.

Aortic valve

The aortic valve consists of three

semilunar cusps (Fig. 2.45), which prevent backflow of blood from the ascending

aorta during ventricular diastole. The valve lies behind the sternum to the

left of the midline at the level of the anterior end of the third left

intercostal space (Fig. 2.32). However, its sounds are best heard over the

medial ends of the first and second right intercostal spaces.

The pulmonary trunk and the ascending

aorta lie within the fibrous pericardium, enclosed together in a sleeve of

serous pericardium anterior to the transverse pericardial sinus (Fig. 2.40).

The pulmonary trunk extends upwards and backwards, while the ascending aorta

initially lies behind it and passes upwards and forwards, overlapped by the

right auricle. At the origin of each vessel are three dilatations or sinuses

(Figs 2.39 & 2.45), one immediately above each of the cusps of the pulmonary

and aortic valves. When ventricular contraction ceases, blood flows into the

sinuses, thus pushing against the cusps and closing the valves. Two of the

aortic sinuses give rise to the right and left coronary arteries.

The pulmonary trunk emerges from the pericardium

and divides into right and left pulmonary arteries in the concavity of the

aortic arch, anterior to the bifurcation of the trachea at the level of the

fourth thoracic vertebra. As the ascending aorta pierces the fibrous

pericardium, it turns backwards and to the left, becoming the arch of the

aorta.

Connecting the aortic arch to the

pulmonary trunk (or to the commencement of the left pulmonary artery) is the

ligamentum arteriosum (Fig. 2.46), the remnant of the fetal ductus arteriosus

which conveyed blood from the pulmonary trunk to the aorta, bypassing the

pulmonary circulation. Occasionally, the ductus remains patent after birth,

giving rise to serious circulatory abnormalities.

The arterial supply to the heart is

provided by the right and left coronary arteries, which arise from the

ascending aorta just above the aortic valve (Fig. 2.47). They supply the myocardium, including the

papillary muscles and conducting tissue. The principal venous return is via the

coronary sinus and the cardiac veins.

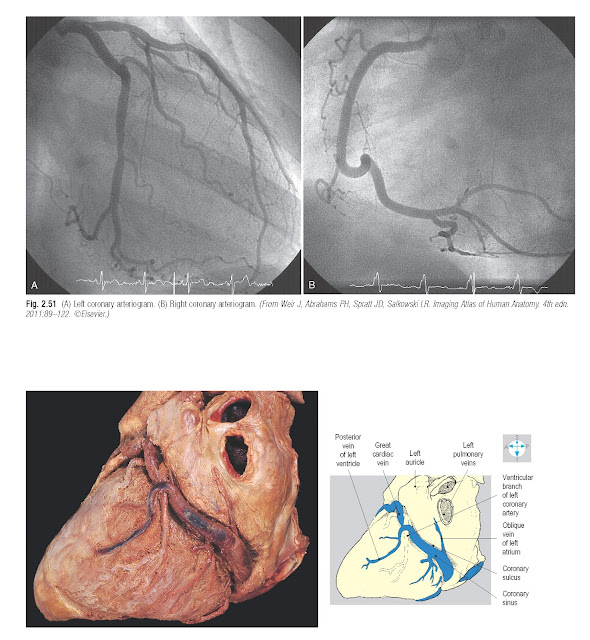

Right coronary artery

This vessel arises from the anterior

aspect of the root of the aorta and descends in the anterior coronary sulcus (Figs

2.47 & 2.48). At the

inferior border, it gives off a marginal branch, which runs to the left towards

the apex of the heart. The right coronary artery continues on the inferior

surface in the coronary sulcus (Fig. 2.49) and terminates by anastomosing with

the circumflex branch of the left coronary artery. On the inferior surface, the

posterior (inferior) interventricular artery arises from the right coronary

artery (occasionally the left coronary artery) and runs in the posterior

interventricular groove towards

the apex. When the

posterior interventricular artery arises from the right coronary artery,

the heart is described as right dominant. The right coronary artery and its

branches supply the anterior surface of the right atrium, the lower part of the

left atrium, most of the right ventricle and parts of the left ventricle and

interventricular septum (Fig. 2.51B). In addition, branches from this artery

usually supply most of the conducting tissue of the heart (p. 56).

This artery takes origin from the

posterior aspect of the root of the ascending aorta and runs to the left behind

the pulmonary trunk where its major branch, the anterior interventricular

artery, arises (Figs 2.47 & 2.50). The latter vessel descends in the

anterior interventricular groove towards the apex of the heart. The left

coronary artery continues as the circumflex artery in the posterior part of the

coronary sulcus and terminates by anastomosing with the right coronary artery.

The vessel supplies the posterior wall of the left atrium and auricle, most of

the left ventricle and parts of the right ventricle and interventricular septum

(Fig. 2.51A).

|

Fig. 2.50 Left coronary artery and its branches, viewed from the

left.

|

Coronary sinus and cardiac veins

Most of the venous return from the

heart is carried by the coronary sinus, which runs along the posterior part of

the coronary sulcus and terminates in the right atrium. The coronary sinus is

formed near the left border of the heart by the union of the posterior vein

of the left

ventricle and the

great cardiac vein (Fig. 2.52), which accompanies the anterior interventricular

artery. Other veins enter the coronary sinus, including the middle cardiac vein

(Fig. 2.53), which

accompanies the posterior interventricular artery. Some cardiac veins enter the

right atrium independently (Fig. 2.48).

|

Fig. 2.52 Oblique view of the coronary sinus lying in the coronary

sulcus.

|

Conducting

system

Coordinated contraction of the

myocardium is controlled by specialized conducting tissues, consisting of the

sinuatrial (SA) node, the atrioventricular (AV) node, the atrioventricular

bundle (of His) and its right and left branches (Fig. 2.54).

|

Fig. 2.53 Posteroinferior view of the termination of the coronary

sinus in the right atrium.

|

The SA node lies in the anterior wall

of the right atrium close to the termination of the superior vena cava. It

occupies part of the root of the auricle and the upper end of the sulcus

terminalis. Numerous autonomic nerves supply the node and modify its rate of

discharge. The SA node usually receives blood from an atrial branch of either

the right or left coronary artery. From the SA node the cardiac excitation wave

passes through the atrial myocardium to reach the AV node.

The AV node lies in the interatrial

septum anterosuperior to the termination of the coronary sinus. It is

continuous with the atrioventricular bundle, which passes through the fibrous

ring separating the atria and ventricles. The bundle gains the upper part of

the interventricular septum and promptly divides into right and left branches.

The AV node and bundle are supplied by branches of the posterior

interventricular artery. Interruption of the arterial supply to the conducting

tissues may result in cardiac arrhythmias.

Lying beneath the endocardium, the

right branch of the atrioventricular bundle descends in the interventricular

septum and often passes in the moderator band (Fig. 2.55) to ramify within the anterior wall of the right

ventricle. The left branch runs on the left side of the interventricular

septum. Both branches divide repeatedly at the ventricular apices and spread

out into the myocardium of the respective ventricles.

|

Fig. 2.54 Location of the conducting tissues.

|

|

Fig. 2.55 Moderator band, seen through a window cut in the anterior

wall of the right ventricle.

|