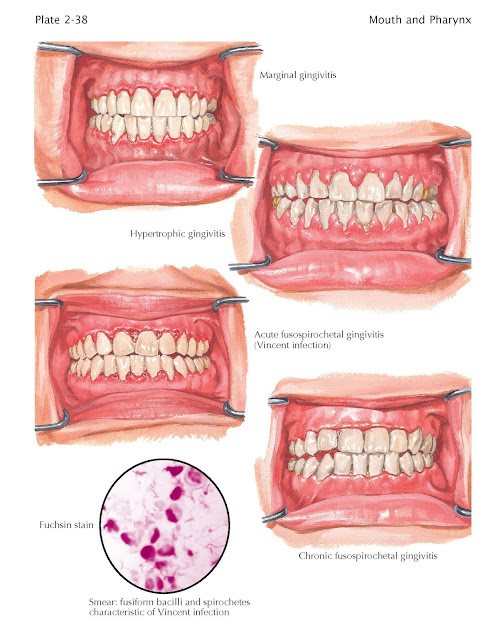

Gingivitis

Marginal

gingivitis is chiefly caused by

local irritating factors, such as calcareous deposits on the teeth, food

impaction, rough or overhanging filling margins and other dental restorations,

misalignment of teeth, open contacts or other morphologic faults causing

improper function, and hygienic neglect. These factors are, of course,

complicated by such conditions as allergies, mouth breathing, medications,

tobacco smoking, and hormonal changes. As with periodontal disease, individuals

may be genetically predisposed to the development of this condition. Marginal

gingivitis is the first stage in a complex periodontal syndrome that is further

characterized by pocket formation and inflammation of the investing tissues

(periodontitis) and, finally, by periodontal abscesses (see Plate 2-36).

Clinically, the gingiva is conspicuous for a shiny pink, red, or even cyanotic

surface, edema, and a strong bleeding tendency of the margins and papillae of

the gum. In the initial stages of the condition, there is a deepening of the

sulcus between the tooth and the gingiva; this is followed by a band of

erythema, indicative of the inflamed gingiva, which can be along one or, most

often, multiple teeth, resulting in edema of the inter- dental papillae that

easily induces bleeding.

Hypertrophic gingivitis describes a frequent variation of the marginal

type of inflammation, depending upon the individual response and the

chronicity. An increase in size of the papillae is more noticeable than that of

the free margin of gum and is especially related to accretions of calculus on

the teeth. Hormonal alterations, as in menstruation, pregnancy, and menopause,

will increase the degree of hypertrophy. Diffuse, idiopathic fibromatosis of

the gingiva, which is free of inflammation, is normal in color, and presents a

uniform proliferation of the gingiva in a firm, bulging mass throughout the

jaw, is another form of hypertrophic gingivitis; it is similar to the gingival

hyperplasia resulting from use of phenytoin.

Although the most common form of

gingivitis, plaque-induced gingivitis, is limited to gingivitis associated with dental plaque and is distinct from other presentations of gingivitis,

the bacterial plaque initiates the host response. The plaque accumulates in the

interdentition gaps, the gingival grooves, and plaque traps that harbor plaque.

The bacteria in the plaque activate lipopolysaccharides or lipoteichoic acid,

which promotes the inflammatory response causing gingival hyperplasia. As the

disease progresses, the bacterial situation becomes more complex, with an

increase in numbers and types of bacteria present.

Necrotizing ulcerative gingivitis, or fusospirochetal gingivitis, commonly known as

trench mouth, is a noncontagious opportunistic infection caused by bacte- ria

indigenous to the mouth in a host with reduced tissue resistance. Predisposing

factors include tobacco smoking, viral respiratory illnesses, poor nutritional

status, psychological stress, and immunocompromised states such as HIV/AIDS.

Chemoradiation therapy may also be a predisposing factor. Local causes include

all conditions promoting growth of anaerobic organisms, such as gum flaps over

third molar teeth, crowded and malpositioned teeth, inadequate contact areas,

food impaction areas, and poor oral hygiene.

The flora of necrotizing ulcerating

stomatitis typically includes one or more types of spirochetes and a fusiform

bacillus. Ulceration and pseudomembrane formation are the specific lesions seen

in this condition.

The acute form presents with a sudden

onset of oral pain and constitutional symptoms of elevated temperature and

malaise; it is more often seen in children or immunocompromised individuals.

Submandibular lymphadenopathy is variable. Severe pain, a strong characteristic,

malodourous breath, and gingival bleeding are marked; objectively, these signs

are related to flat, punched-out, grayish ulcers, which erode the tips of the

papillary gingivae and spread to the margins, which are covered by a thin

diphtheritic-like membrane. On slight pressure, bleeding may occur from all

affected areas. In severe cases the lesions spread to the tongue, palate,

pharynx, and tonsils; profuse salivation, a thickly coated tongue, and bleeding

are seen.

Chronic necrotizing gingivitis is a milder form of this disease; it exists from

the outset or is a slowed down phase of the acute form. Subjective symptoms are

much reduced. The first awareness is of bleeding when brushing the teeth.

Careful retraction of the papillae may be necessary to reveal the typical

necrosis. Pain is usually absent. The typical odor develops later because

destruction proceeds slowly. The response to therapy is far slower in

long-established cases, and recurrence is a constant hazard. As the

architecture of the gingiva is altered, anaerobic areas are created and food

retention is abetted, so that therapy against the infection alone is of only

momentary value; it must be directed to a restoration of the proper gingival

form.