FRACTURE OF DISTAL

HUMERUS

In adults, fractures of the distal humerus often require surgical fixation

because they are usually caused by a high-energy injury and frequently are comminuted

and/or intra-articular in location. Fracture patterns include supracondylar,

transcondylar, intercondylar (T or Y), lateral or medial condyle, or epicondyle

and isolated capitellar or trochlear fractures. Intra-articular fractures may

be difficult to adequately assess on plain radiographs; therefore, CT scans may

be needed.

Surgical fixation can be with plates

and screws, or screws alone, depending on the particular fracture pattern.

Joint replacement has also become an option for distal humerus fractures that

may be too comminuted to be stabilized with plates and screws.

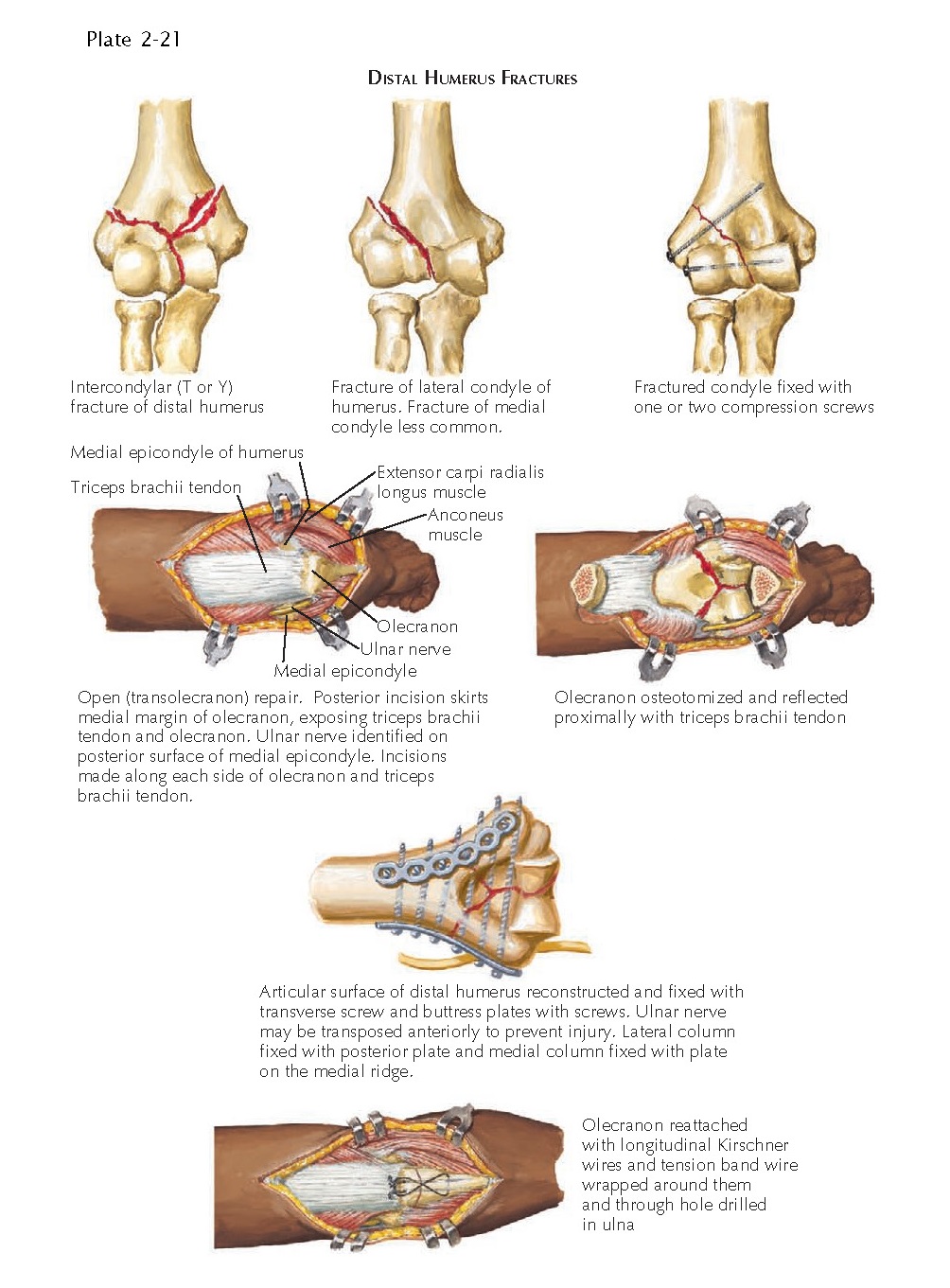

Complex Intra-articular

Fractures

Comminuted intra-articular fractures

of the distal humerus are among the more challenging orthopedic injuries, and

their reconstruction requires considerable surgical skill (see Plate

2-21). The major

complications include restricted elbow motion and early degenerative joint

disease.

Surgical fixation of comminuted

intra-articular fractures can be problematic: the distal fragments are small,

minimizing the number of available screw sites, and the fragments are primarily

cancellous bone, which compromises screw purchase. In addition, the surface of

the distal fracture fragments is primarily articular cartilage, which must be

protected, and the complex topography of this region can make reconstruction of

the normal anatomy difficult.

The structure of the distal humerus is

conceptualized as two bony columns diverging from the shaft. The medial column

includes the medial pillar of the distal humerus, the medial condyle and

epicondyle, and the trochlea. The lateral column includes the lateral pillar of

the distal humerus, the lateral epicondyle and condyle, and the capitellum. To

approach and fix intra-articular fractures of the distal humerus, an

intra-articular osteotomy of the olecranon is usually performed and the

olecranon and the aponeurosis of the triceps brachii muscle are reflected

proximally, exposing the entire distal humerus (see Plate 2-21). The ulnar nerve is also identified and

typically transposed as part of the surgical approach. Internal fixation of the

distal humerus first involves reconstructing the articular surface and holding

the fragments together with transverse Kirschner wires or lag screws. The

articular surface is then reattached to the shaft with plates and screws to provide stability in both

the anteroposterior and mediolateral planes. Current techniques utilize

bicondylar plating with precontoured plates that match the anatomy of the

distal humerus. Bicondylar plating can be performed with the plates at right

angles to one another (medial plate and posterolateral plate) or straight

across from one another (medial plate and lateral plate). The olecranon is

reattached with a precontoured plate to fit the olecranon or a tension band

wire (see Plate 2-21). Newer surgical approaches have been developed and are

now being utilized that avoid the need for an olecranon osteotomy while still

providing enough visualization of the distal humerus from appropriate fixation.

This can speed up recovery after surgery and avoids the risk of developing a

nonunion at the osteotomy site.

Total elbow arthroplasty has also

become an option for comminuted distal humerus fractures. In elderly patients

with poor bone quality, such fractures may be unable to be stably fixed with

plates and screws. Joint replacement allows early range of motion and function

for these otherwise devastating elbow injuries, without requiring bony healing

(see Plate 2-22). In younger patients with severely comminuted

distal humerus fractures that cannot be reconstructed with plates and screws,

elbow hemiarthroplasty is becoming a surgical alternative in select cases. This

replacement of only the humeral side of the elbow is a newer option in this

patient population that is typically considered too active for a complete elbow

replacement.

Early elbow range of motion is

important after plating or elbow arthroplasty to avoid stiffness. Protected

active and active-assisted exercises (flexion-extension, pronation-supination)

are encouraged soon after surgery to maintain range of motion in the elbow

joint.

Fractures of Lateral Condyle

Fractures of the lateral condyle can

involve the capitellum alone or extend medially to involve the lateral portion

of the trochlea (see Plate 2-21). Fractures of the lateral condyle are more

common than those of the medial condyle and are usually displaced and require

surgical fixation. As with any intra-articular fracture, open reduction and

internal fixation is performed to reestablish the articular surface as

accurately as possible and to allow early active motion. A plate and screws or

screws alone can be used for fixation, depending on the fracture pattern. In

fractures of the lateral condyle, both in adults and in children, it is

important to preserve all the soft tissue attachments, particularly

posterolaterally, to maintain the blood supply to the fragment. With rigid

internal fixation, the patient can begin active motion as soon as the soft

tissues have healed.

Fractures of Capitellum

Fractures of the capitellum alone are

uncommon and may be difficult to diagnose if the fracture fragment is very

small. Any effusion within the elbow joint together with displacement of the

fat pads on plain radiographs suggests either a capitellar fracture or other

nondisplaced fracture near the elbow.

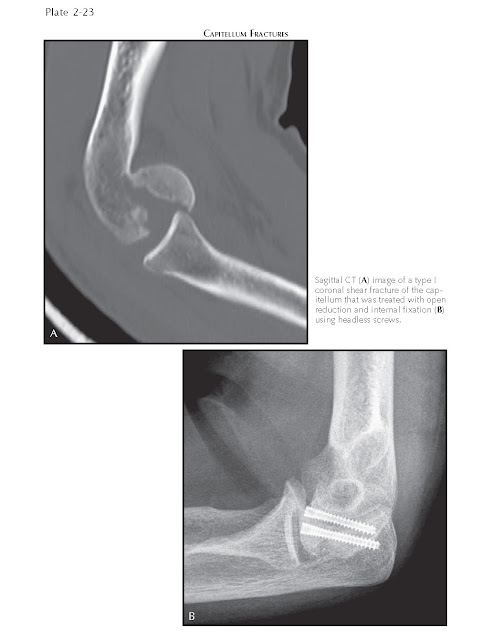

There are four types of capitellar

fractures. The type I (Hahn-Steinthal) fracture is a coronal fracture that

involves a large part of the osseous portion of the capitellum and is typically

treated with open reduction and internal fixation with one or two screws. This

method makes early joint motion possible in rehabilitation. These screws often

need to be placed on the articular surface in an anterior to posterior

direction and, therefore, are headless and countersunk (see Plate

2-23). The type II

(Kocher-Lorenz) fracture is a sleeve fracture that involves primarily the

articular cartilage with very little underlying bone. The fragment is often too

small to be fixed, and treatment includes excision of the fragment. Type II

fractures cause few subsequent problems in the elbow joint. Type III fractures

are comminuted and also may be difficult to fix, and a type IV fracture is

similar to a type I fracture, except that it extends more medially and includes

a major portion of the trochlea.

Fractures of Medial Epicondyle

The medial epicondyle is the common

origin of several flexor muscles of the hand and wrist. When the medial

epicondyle is fractured, the flexor muscles pull the fragment distally. The

injury is often accompanied by valgus instability of the elbow if the

collateral ligament is affected and by injury to the ulnar nerve. If there is

significant valgus instability of the elbow, the epicondyle must be reduced to

its anatomic position and secured with a pin or a screw. During the surgical

procedure, care must be taken to protect the ulnar nerve from inju y, and ulnar

nerve transposition may be necessary.