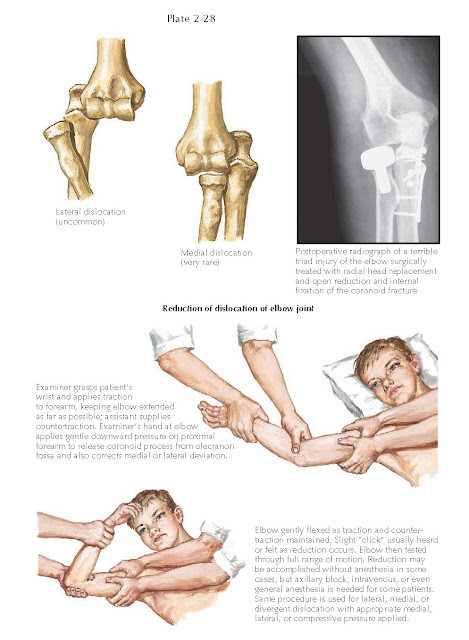

DISLOCATION OF ELBOW JOINT

Dislocations of the elbow joint are the most common dislocations after

those of the shoulder and finger joints. Swelling, pain, and pseudoparalysis of

the arm are acute signs and symptoms of dislocation, and elbow deformity is

visible on both clinical and radiographic examinations.

Acute elbow dislocations are

classified as anterior or posterior, with the direction determined by the position

of the radius and ulna relative to the humerus. In addition to the anterior or

posterior direction of dislocation, the forearm bones can also be displaced

medially or laterally. Posterior elbow dislocations are by far the most common

type and usually result from a fall on an outstretched hand. The rare, but

extensively studied, anterior dislocation of the elbow is usually an open injury

and may lacerate the brachial artery. Rarely, the radius and ulna dislocate in

different directions, an injury called a “divergent” dislocation.

Dislocations of the elbow result in a

pattern of ligamentous injury that depends on the direction of dislocation. For

posterior dislocations, the ligamentous injury typically starts laterally,

disrupting the lateral collateral ligament complex first; it then moves medially,

disrupting the anterior and posterior joint capsule, followed by the medial

collateral ligament complex. Elbow dislocations are sometimes accompanied by

fractures as well, including fractures of the medial or lateral epicondyle,

olecranon, radial head or neck, or coronoid process of the ulna. As discussed

previously, the combined injury pattern of an elbow dislocation associated with

both a radial head fracture and a coronoid fracture has been termed a terrible

triad injury.

Fracture-dislocations of the elbow,

especially displaced fractures of the olecranon, coronoid process, and radial

head, often require surgical fixation to ensure longterm stability and function

of the joint. An avulsed medial epicondyle can become wedged inside the joint

during reduction of the dislocation. Only occasionally can closed manipulation

free the avulsed fragment from within the joint; arthrotomy is usually needed

to remove the fragment and return it to its anatomic position.

Reduction Of Dislocation Of Elbow

Joint

A posterior dislocation of the elbow

is reduced with distal traction. While an assistant secures the proximal

humerus, the examiner applies traction in the line of the forearm, holding the

forearm supinated, and then gently flexes the elbow joint to allow the humerus

to reduce into the olecranon fossa. If the elbow is reduced immediately after

dislocation, complete muscle relaxation may not be needed; if treatment is

delayed, conscious sedation, axillary block, or general anesthesia is used to

induce complete muscle relaxation. Radiographs should be obtained after

reduction to confirm that the elbow joint is concentrically aligned. The neurovascular

status of the distal limb is checked both before and after reduction. Any

changes or abnormalities suggest entrapment of a nerve or vessel during

reduction, which must be relieved promptly to prevent a long-term deficit.

After the initial reduction, the

examiner moves the elbow through a full range of motion to assess its stability

and to check for crepitus in the joint. Crepitus strongly suggests loose

fracture fragments in the joint. If the elbow remains stable through a full

range of motion, it is immobilized in 90 degrees of flexion in a posterior

splint. The neurovascular status of the limb is monitored frequently while the

elbow is splinted to ensure that a deficit does not develop. Most isolated

elbow dislocations are treated with splint immobilization for a short period of

time (1 to 2 weeks) before beginning range-of-motion exercises. The exercises

should be gentle initially but as active as symptoms permit. The physician’s

assessment of the degree of stability after reduction helps determine what

range of motion to allow and when to begin the exercise program.

Elbow dislocations cause few long-term

complications. By far the most common is residual joint stiffness, particularly

loss of extension. Although some degree of stiffness almost always persists,

early active motion can minimize this problem. The older the patient, the

earlier active elbow movement should be started.

Myositis ossificans, another

complication of elbow dislocation, results from muscle injury at the time of dislocation.

Myositis ossificans is more likely to develop after severe injuries, such as

those that are high energy or associated with fractures, and when treatment has

been delayed. Early passive motion is discouraged in patients with dislocation

and muscle injury because excessive muscle stretching may precipitate the development

of myositis.

Recurrent dislocations after an

isolated elbow dislocation are uncommon and are thought to be due to extensive

collateral ligament damage (medial and lateral) or an occult fracture. Surgery

to repair or reconstruct the collateral ligaments may be necessary in this situation.